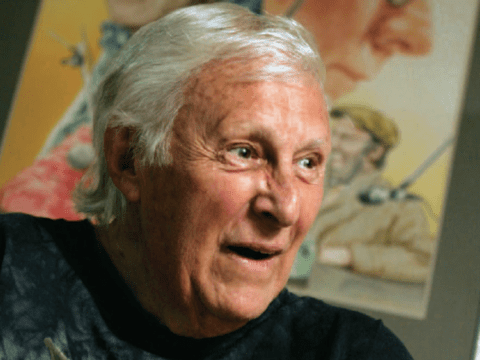

Former Iraq hostage James Loney is the first recipient of the Craig Chaplin Memorial Award from United Theological College in Montreal. He talks with David Wilson about how captivity tested his faith and raised his profile as an activist.

DAVID WILSON: The Craig Chaplin Memorial Award recognizes the contributions to ministry of lesbian and gay people. You have been a social justice worker, a Christian Peacemaker and a hostage. Today it seems your name is most closely linked with gay- and lesbian-rights activism. Is that how you see yourself?

JAMES LONEY: It’s profoundly important to me, but I am not interested in an activism narrowly focused on one identity. The justice issues that we’re facing in the world today are all interlinked. Justice for queer people cannot be achieved without justice for all people who are marginalized, whether it’s on the basis of race, class or national identity. All of these things cannot be separated from the environment and what we do to ensure a future for our children and our planet. I want people to look at things in a holistic way.

Part of what happens to gay and lesbian people is that we are seen in only a very narrow way, through our sexual orientation, through particular sexual acts. I’m not interested in perpetuating that kind of perception.

DW: Nevertheless, you have clashed publicly with your own denomination over gay and lesbian issues. To what extent is progress on this front possible in the Roman Catholic Church?

JL: Progress is always possible, and I think it’s happening at the grassroots level. We’re in a time in the Catholic Church where the hierarchy is threatened, disconnected and out of touch. The hierarchy is in a crisis of credibility and authority that is perhaps unprecedented. They’re reacting by trying to impose a narrow definition of orthodoxy that reinforces their power. But the house is crumbling at the foundations.

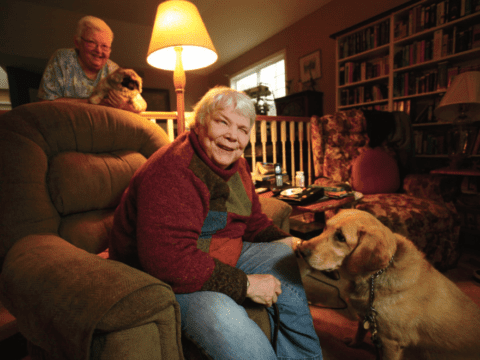

Here’s an example. Just after I got home from captivity, my partner, Dan Hunt, and I went to mass at my parents’ church in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. People came up to us and gave us hugs and said how happy they were that we were there. The fact that we are gay partners wasn’t an issue. That’s what I mean about the grassroots level.

DW: In your convocation address at United Theological College, you spoke about moving out of the darkness. What does this mean for gays and lesbians in the church?

JL: We gays and lesbians know from experience how damaging homophobia is to us, and how damaging it is to straight people, too. In the Christian community, that voice from the outside, from the margins, has the possibility of liberation within it. If the church will listen, then the whole church will benefit, just as it does in listening to the experience of the suffering of the poor. It’s a call to right relationship.

DW: The fact that you are gay was kept a closely guarded secret during your captivity. How experienced were you at keeping a secret like that?

JL: If you are queer and growing up in a homophobic society, you are forced, for your own survival, to fit in. It’s called “straight-looking and straight-acting.” In captivity, I suppose I had to draw on all that training.

DW: Your captors are in custody. You have said that you will not testify against them. Would you want to meet them again? If you did, what would you say?

JL: Yes, I would like to meet them. But what would I say…?

DW: Do you forgive them? Can you forgive them?

JL: Forgiveness is a funny thing, a process more than a definitive act that you do and then walk away from. Forgiveness was integral to the process of captivity itself. I had to continually try to be forgiving, because if I wasn’t I would become consumed by anger and rage, and I would suffer more. The more I tried to understand and have compassion for them, the less I suffered.

DW: Did you find yourself looking deeper into your faith as this process evolved? Or did it come naturally?

JL: It sounds like a cliché, but it was sort of a test of faith. When we are Christian, we are followers, disciples. We believe in a story and a set of teachings and principles. What does my commitment to non-violence mean when I have my freedom taken away, when I don’t know whether I will live or die, when I am cold, hungry, bored and afraid? What does loving my enemy mean? Keeping faith is about holding on to who we are, and trusting in love and resurrection and forgiveness and God’s power.

DW: Did you ever say, “God, why is this happening to me?”

JL: Obviously I felt what was happening to me was wrong. But it wasn’t just about me; it was about a whole massive system of causes and effects, and all the massive, catastrophic ramifications of war that were playing out in ordinary people’s lives in Iraq. The four of us were swept up in this massive tidal wave. It wasn’t about God being unfair to me.

DW: You’re writing a book about your captivity. Do you feel this is something you have to do to make sense of what happened?

JL: Writing has always been an important way for me to express myself. When something’s happening I often translate it into words in my mind, as if they were on a page. So, in captivity, here we are in this room. No one knows where we are. I don’t know where I am or what’s going to happen. We were given notebooks. So I imagined what we were living was a play and wrote it as dialogue. It was partly about expressing myself but it was also partly a distancing mechanism.

I don’t enjoy writing. I find the process very hard. It would be a lot easier not to write it, but that would be betraying something in myself. The therapy will be in having it done — a sense of relief that I can move on.

DW: How do you see things playing out after the book is done?

JL: In my own quiet way, I hope to continue to help gay and lesbian people be seen as human beings, rather than the “other” — not to make a big production out of it, just to say that this is who I am and it’s part of all the other stuff.

When I was in captivity, Canada saw me as this nice guy from Sault Ste. Marie with a nice family, and so on. Many people were moved by my story, and many people prayed for me, but the full story of who I was couldn’t be told.

Then I came back and said, “By the way, I’m gay and this is my partner, Dan Hunt,” and I wondered what it would mean for some people. All of a sudden they’re finding out they prayed for a gay guy. For most people, it seems not to have made much of a difference.

But homophobia is still out there. There are teenage boys who are killing themselves, and families that are being torn apart because of it. Someone shouted “Die faggots!” on our front lawn late at night. A Catholic leadership camp I worked at closed after I introduced Dan to the media. Addressing this is very important to me.

DW: As a Christian Peacemaker, you would go to troubled places and accompany people in danger. Is that rather like what you’re doing now, with lesbian and gay people?

JL: No. I’m in the same boat as them. I still face homophobia. It happened during captivity; it’s happening in my church. I’m one of those people walking in darkness. They’re accompanying me as much as I’m accompanying them.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s July/August 2008 issue with the title “‘I still face homophobia. It happened during captivity; it’s happening in my church.’”