I am fundamentally shy, embarrassed by too much attention. Being swept up by the phenomenon of Facebook four years ago only underscored how ill-suited I am for relentless exposure through online social networking. When near-strangers approached me on websites with the familiarity of old friends, I felt fraudulent if I returned it in kind — bothered by the banalities of digital interaction and the limitations of expressing myself online. Still, I couldn’t resist. Indulging my curiosity for social media meant surrendering part of myself to it.

Inside a trendy brick-and-chrome-themed coffee house in downtown Toronto, I recently shared this anxiety with social media enthusiast Nick Valentino. Here, 20-somethings, wearing hooded sweatshirts and goose-down coats, sit alone with their lattes, surveying messages on laptop computers. Meanwhile, two women chat incessantly, nonchalantly scanning their smartphones for emails.

“Myself, I spend two to three hours a day reading and tweeting online, usually while commuting back and forth to work,” Valentino tells me over the roar of espresso machines and fingers feverishly banging away on computer keyboards. At times, the 36-year-old website developer talks with an instant-message brusqueness. Other times, he enthuses expansively about online social networks while trying not to sound too much like a fan.

Valentino was an early user of the social media website Twitter, which was launched in July 2006. Today he has three accounts. He admits he likes the acknowledgment Twitter brings — a response or retweet. “It’s exciting; you’re letting these people inside in what seems to be the safest way possible,” he says. “It’s a strange hybrid of the impersonal and personal.”

Earlier that day on Twitter, Valentino mused about mouth-watering pies, public transit woes and Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s vow to dismantle “the most democratic campaign finance laws in the world.” In one tweet he asked, “Was George Washington the victim of 18th century airbrushing?” In another, he riffed on a possible sequel to The Big Lebowski: “Guessing the plot will be about getting a new rug.”

Within a single generation, social networking on the Internet has reshaped modern culture and revolutionized how we relate to each other. For many people under the age of 50, online social networks have replaced television, newspapers and radio as their primary sources of entertainment and information. Social networking sites such as Facebook and Twitter are the first places they go to find love and ask spiritual questions. They have helped not only to organize political activists but to extend their reach in places such as the Middle East and Europe, accelerating movements for change. Inside these electronic villages, we can connect with as many people as we like, simultaneously or successively. We can rebuild — albeit virtually — the kind of old rural communities where everyone knew everyone else.

But we’ve also lost control, say critics such as Steve Wozniak, the founder of Apple computers. “We can’t turn off our Internet; we can’t turn off our smartphones; we can’t turn off our computing devices,” he told CNN in December. So what are the implications of living in such a wired world? What impact will this constant connectivity have on future generations? Culture and technology critics focus on not only the exciting possibilities but also the distressing inevitabilities of this new society: the lack of authenticity, the loss of empathy for others and an erosion of physical relationships.

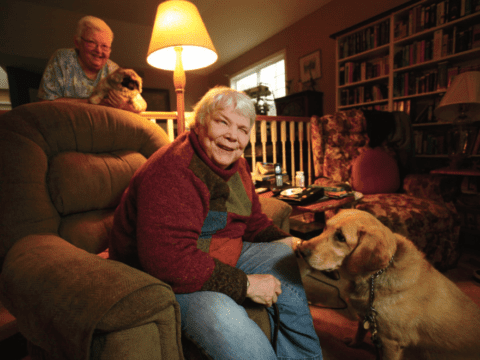

Canadians are right in the thick of the social media revolution. According to a 2010 study on Internet use, we spend more time online than users in any other country. About 68 percent of us are now online, and on average we log about 42 hours on our computers or smartphones every month. Statistics Canada says Internet use has increased steadily since 2000, with seniors being the fastest-growing segment of the wired population.

Canadians are also enthusiastic users of social media — more than 17 million are on Facebook, which places us 10th on the list of countries with the most accounts. Worldwide, Facebook has attracted more than 600 million users; 200 million and counting use Twitter, generating about 140 million messages — or tweets — a day.

With all of this interaction, you might guess that human relationships are flourishing as never before. You’d be wrong, says Robin Dunbar, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at Oxford University and the author of How Many Friends Does One Person Need?

Facebook friends shouldn’t be confused with real friends, he says. “Issues of social status and approval and the potential permanence of Facebook posts subvert all tendencies toward the types of authentic, risky communications that might lead to healthy and interesting relationships.” Put simply, people online are who they pretend to be, not who they actually are.

Dunbar argues that social networking has allowed us to amass thousands of acquaintances, but sites like Facebook and Twitter have not yet devised a way to cut through the “clunky, old-fashioned nature of relationships” themselves. Our circle of actual friends, he says, remains “stubbornly small,” limited not by technology but by human nature. Dunbar’s research suggests humans max out at about 150 meaningful relationships.

“The emotional and psychological investments that a close relationship requires are considerable, and the emotional capital we have available is limited,” he says. “In the end, it’s actually meeting face to face — actually doing stuff together — that really makes the difference. And if you try to do it virtually, you are not only having increasingly impoverished relationships with people; you’re blocking the opportunity to go and meet new people and engage in the real live world.”

Our online acquaintances can be great sources of new ideas and information, and the Internet allows us to harness the power of these networks with “marvellous efficiency,” but they are distant, flimsy connections, according to award-winning writer Malcolm Gladwell. In a New Yorker article last year, the Canadian-born author of The Tipping Point and Outliers argued that online social networks are built around “weak ties.” The “evangelists of social media,” he wrote, “seem to believe that a Facebook friend is the same as a real friend and that signing up for [organ] donor registry in Silicon Valley today is activism in the same sense as sitting at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro in 1960.” Facebook doesn’t succeed in motivating people to make a real sacrifice, he continues. “If you are of the opinion that all the world needs is a little buffing around the edges, this should not trouble you. But if you think that there are still lunch counters out there that need integrating it ought to give you pause.”

Researchers at the University of Texas, however, have reached a different conclusion. According to a study they conducted last year, social media websites strengthen ties in unique ways for different age groups. “Facebook is not supplanting face-to-face interactions between friends, family and colleagues,” media professor S. Craig Watkins told Reuters in November. “In fact, we believe there is sufficient evidence that social media afford opportunities for new expressions of friendship, intimacy and community.”

Last year, on the eve of Valentine’s Day, hundreds of people flocked to inaugural “Flitter” parties in Canada. They tweeted flirtatiously on their iPhones and BlackBerrys, vying for the attention of other single “tweeters.”

For Vancouver native Meg Fowler and her partner Gradon Tripp, love steadily bloomed 140 characters at a time. They both started using Twitter in early 2008. Soon they began to follow each other’s tweets and blogs. What began with mundane messages, like “I’m drinking coffee, so are you,” rapidly progressed into private notes between the two. After months of long-distance communication, they decided to meet in person in Boston, where Tripp lives and works. Sparks flew, and in April 2010, Fowler moved to Boston to live with Tripp.

“(Gradon) seemed nice and articulate online . . . and when I clicked through to his blog, he didn’t look too shabby, either,” Fowler, 36, explains. “But five minutes after I met him, I was completely comfortable. It’s impossible to describe how that was possible because I know it sounds loopy, but perhaps it was the result of the hours of online conversation prior to that fateful day.”

She continues, “Sure, [social media] comes with all the dents and frustrations that humans have in real life. It exposes you to weird people and not-so-great people. But with it comes an extra layer that can embolden people to say things they otherwise might not mention….It not only leads to new relationships, but new opportunities, too.”

Fowler, a communications professional and co-ordinator of the charity group Social Media for Social Change, admits that not everything she says is particularly interesting or meaningful. But as she pointed out in a tweet from February 2008, “I know a lot of people who don’t need back story. They just take what they see. Just for those that do, I want to be warts and all.”

What does the explosion of online networks mean for communities of faith? Aaron McCarroll Gallegos, the digital content strategist for The United Church of Canada’s interactive WonderCafe.ca website, suggests that “WonderCafe, and its French-language partner site, Caféchange, offer people in the United Church a unique way to connect with each other across regional and congregational lines. To others, they have offered the first real opportunity they’ve had in their lives to discuss spiritual questions. In our post-Christian society, situations like this are more common than many may think.”

The “give-and-take, more transparent character of social media,” he adds, helps the church shed its “sage on the stage” image in favour of a “guide on the side” model — something the church’s research has shown younger Canadians are looking for.

But surely biblical community requires more than fan pages and tweets?

As it happens, more people are using the Internet for religious and spiritual purposes than banking or dating services, according to Christopher Helland, an associate professor of the sociology of religion at Dalhousie University in Halifax. In a paper published in 2008, Helland examined the impact of computer-mediated communications on a variety of religious traditions. He cited a recent study by the Pew Internet and American Life Project, which found that 64 percent of wired Americans exercised their faith online. Although no comparable studies have been completed in Canada, these numbers reflect all North American Internet activity, Helland said.

But there’s a downside to Internet religion. “It’s amazing how quickly people can get nasty online,” Helland tells me, pointing to Second Life, a virtual world on the Internet where people can attend worship, among other things, in avatar form. Some users do “inappropriate and horrific things” that they would never do in an actual sacred space. The Church of England, which hosts an eye-catching, three-dimensional environment, has booted out thousands of people for their improper behaviour, he adds. “For some, there’s maybe not as strong — and maybe not as deep — a religious commitment online. There aren’t the same ethical consequences for bad behaviour as there are offline. We all know the rules and regulations of traditional churches. They’re sort of embedded, even in the architecture.”

At 10:53 p.m. on Christmas Day last year, Simone Back, a 42-year-old charity shop worker from Brighton, U.K., posted her final Facebook message: “Took all my pills be dead soon so bye bye every one.” British newspapers reported that as many as a thousand “friends” looked at her page that night, and not a single person called for help. In fact, some Facebook users even taunted Back over her final status update, with one declaring that the fatal overdose was “her choice.” Another dismissed Back’s cry for help, saying, “She’s not a kid anymore.”

Sociologist Sherry Turkle says that the more we immerse ourselves in online social networks, the more we sacrifice in the way of depth and empathy.

“We have invented inspiring and enhancing technologies, yet we have allowed them to diminish us,” writes Turkle in Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. In the book, Turkle paints a dismal portrait of human disconnectedness. She describes teenagers who are shaped not by self-exploration but by how they are perceived by others online, and mothers who are better at texting their children than talking to them. According to Turkle, users’ ability to relate to others spontaneously has atrophied as a result.

I asked Derrick de Kerckhove about why social media networks seem to differ from the corporeal kind. De Kerckhove is the former director of the University of Toronto’s McLuhan Program in Culture and Technology and author of The Skin of Culture and Connected Intelligence. He explains that social media networks are global pulses emanating from individuals and connecting with others who are like-minded but not known. With real-life relationships you get a buzz — from the body, from movement, from just being somewhere. “You’re not going to get that kind of buzz if you’re exclusively online.”

But de Kerckhove says there’s nothing to fear— social networks are another chapter in the story of language and technology. “We must always keep in mind that the big metamorphoses going on right now are the consequences of human languages being reprocessed by electricity,” he says. “The first big transformation occurred when language emigrated from the bodies of speakers to text written on walls, papyrus, animal skin and later paper. These shifts were accompanied by several revolutions, psychological and social. . . . So in effect, being human is now subjected to language transported by electricity, which is moving us into very different kinds of social individual conditions.” Personally, de Kerckhove has opted not to have a Twitter account— he prefers socializing face to face.

Back in Toronto, Nick Valentino sips his now-lukewarm coffee. Almost invisible in the vastness of the coffee house — dotted with blinking laptop and smartphone screens — he reflects on what all this 24-7 connectedness might mean.

“When the first novel was written, they thought it was going to poison people’s minds, right?” he quips. “Sure, I see [online social networking] bordering on egotism sometimes. But I feel it enriches me and has put me in touch with good friends — people I wouldn’t have been able to connect with in real life. If I’m ever in Philadelphia, I wouldn’t hesitate to contact my Twitter followers and invite them out to coffee.

“Does it mean less time reading War and Peace? Absolutely. But is that necessarily a bad thing?”

For the record, Valentino has posted poetry on Twitter, too — daily and in exactly 140 characters. In March 2009, Valentino wrote in a self-serious tone, “Lately buoyed by the joy of sharing, a waiting message brings spirits crashing. Hope languishes, lies fallow, like too ripe fruit unplucked.” The following month: “Yet, not quite the fetid landscape some might have us believe. These pre-drawn worlds still inspire, provide a fertile ground for imaginings.”

For all their slick certainties, Facebook and Twitter may one day peter out. But there will undoubtedly be successors. The world is irrevocably binary. You’re either wired or you’re not. You’ve either given “thumbs up” on Facebook and tweeted on Twitter, or you’re curiously left on the sidelines. Like it or not, social media is a virtual experience that is pop cultural, political, amorous and, yes, even spiritual — perhaps just the stand-in we need for a real world that is fractured and ailing.

As the 17th-century philosopher René Descartes said, “I tweet, therefore I am.” Well, he would have said it if he were alive today.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s May 2011 issue with the title “Alone together.”