Jean Little is on her knees beside a young boy’s bed. Her great-nephew, Ben, is nowhere to be found, and she is desperate. Her sister, Pat de Vries, scours snowbanks outside while Ben’s sister, Jeanie, grows increasingly upset. There is nothing left to do but pray. “Please, Lord,” Little implores, “help us find Ben.”

Whereupon Ben pops out from beneath his bed where he had been sleeping.

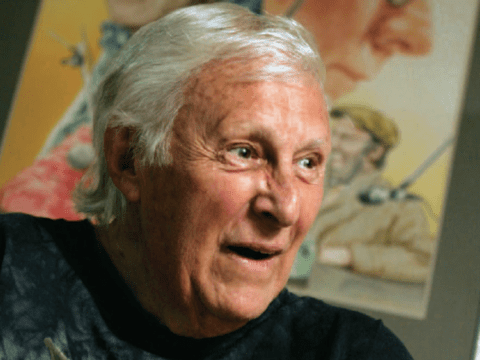

Little can smile about it now as she tells this story from real life. Publicly, Little is best known for fiction. One of Canada’s most-loved children’s authors, she has published more than 40 books. But even in her fiction, real life is often not far away. Legally blind since birth, Little is a children’s writer who addresses disability and adversity frankly; her characters learn to cope and flourish amid their challenges rather than receiving magical cures or solutions. Her books have earned her six honorary degrees, numerous awards and membership in the Order of Canada. She has been a member of The United Church of Canada almost her entire life.

Now 77, Little could be expected to rest on her laurels, but tragic events have intervened. Little and her sister, de Vries, 71, are raising two teenagers, Jeanie, 18, and Ben, 13, the children of Pat’s adopted daughter, Sarah de Vries. Addicted to narcotics and working in the sex trade in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, Sarah was unable to care for the two children. In 1998, she went missing. Her DNA, police say, was found on the farm of Robert Pickton in 2002. He was subsequently charged with her death.

The partnership between the sisters is unique, and their challenges are many. But this is a family where deep loyalty and faith are bred in the bone. “It’s not always easy,” Pat de Vries declares, “but it works, because we want it to work.”

To say that this partnership began in 1993 when the sisters decided to sell their respective houses and jointly purchase a rambling stone house outside of Elora, Ont., would be to do the relationship an injustice. The sisters, both born in Taiwan to Canadian medical missionaries, have always been close. When the family moved to Guelph, Ont., during the Second World War, the sisters shared a room and a bed. Jean, six years older and always a creator of stories and games, developed a bedtime ritual. “Truce, Elf,” she would say as she pressed her hand to her sister’s. “Truce, Goblin,” the younger sister would reply. Even when Pat married and moved to Vancouver and Jean remained in Guelph living with their mother, the bond between the sisters remained strong. “I always had this solid wall of love and support behind me,” de Vries remembers. “A big part of that was Jean.”

When Sarah gave birth to Jeanie in 1990, Pat hadn’t even known her daughter was pregnant. But Pat’s decision to raise Jeanie was immediate and final. “I wanted to keep her in the family so that Sarah, if she got it together, would have something to come back to….She had done something glorious. She had brought this beautiful little girl into the world, and Jeanie should stay as a part of her life.”

Six years later, Ben was already four months old and living with a foster mother in Vancouver when de Vries learned of his existence. The sisters set the wheels in motion to have Ben also put in their care.

When I ask Little what it’s been like raising two kids this late in life, her first answer is “tumultuous.” “It’s not been easy,” she declares, “and it still isn’t easy. We’re not of their parents’ generation, we’re of their grandparents’.” The children were born addicted to narcotics, and both have learning difficulties. “We’ve certainly had problems,” Little confesses, “but also joy, great joy.”

More than half of Jean Little’s literary output has occurred since combining houses with de Vries. There is no doubt that living with children has been an inspiration, but practically speaking, the partnership thrives on distinct roles performed by each sister.

“Jean’s the breadwinner,” says Jenny Stephens, a longtime family friend. “She takes that very seriously.”

At this point, retirement is financially impossible for Little, but the truth is, she can’t not write. During the family’s recent move to a more modest house in Guelph, Ont., Little’s computer, specially fitted with software that allows her words to be read back to her as she writes, wasn’t hooked up. “It’s like I’m an addict, I go into withdrawal….I just don’t function very well.”

De Vries, however, describes herself as “the errand runner, the cleaner-upper, the cook and the grandmother.” She is mostly responsible for decision-making regarding the children, though she takes Little’s advice and input. “I listen to her,” de Vries says, “but I don’t always agree with her.”

“People keep telling me they couldn’t live with their sister,” Little says, “and I say, ‘I couldn’t live without mine!’” That mutual support helped them get by, one day at a time, when Sarah went missing. Little’s trademark gregariousness and wit disappear in speaking about it: “It was a strange time,” she says, “but we did have each other, and we had Jeanie and Ben.”

On any given evening these days, you can find the sisters engrossed in a game of Braille Scrabble or cribbage, or hear de Vries reading to Little in the living room. De Vries helped choose the title for Little’s new novel, Exiles from the War, published this month. And although de Vries was recently nominated for a YMCA-YWCA Woman of Distinction Award for her social-justice work through the former Chalmers United, when she talks about her work — which has led to hundreds of people in Guelph receiving weekly food, clothing and support — she continually acknowledges Little’s contributions by using the pronoun “we.”

The family has always operated as “we.” Jenny Stephens remembers that even though the sisters’ mother, Dr. Flora Little, wasn’t much more than five feet tall, “she was a feisty woman, passionate about social justice and fairness.” In first drafts of Exiles from the War, Little’s editor wondered just how many people the mother character could shelter within the family home. It was something Flora Little did all the time. “That’s how we were brought up,” Little says. “If somebody needs you, you just do it.”

Little’s most recent novels reflect the world she’s encountered in the past years. The subject matter is grittier, more raw. Willow and Twig, for example, is about a brother and sister who, abandoned by their mother in Vancouver, come to Ontario to live with their grandmother and great uncle. Dancing Through the Snow, named after lines in a Voices United hymn written by Eileen Spinelli, is about a girl in foster care who finds healing when caring for an abandoned dog.

One of Little’s novels is titled The Belonging Place, and it is quite possible, she muses, that all of her novels are about such a place — “looking for it, making it, finding it.” In the future, Little has plans to co-write a book with Jeanie, her great-niece.

In the meantime, the sisters’ unique and wonderful partnership continues amid the demands of day-to-day life and the occasional family drama. De Vries articulates how it all works: “Everyone in our family has always been supportive of each other, and Jean and I are certainly that for each other and always have been. We learned that from the cradle, just what love’s all about.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s February 2010 issue with the title “Jean Little’s grown-up story.”