About 10 years ago, Cate Cochran prepared for her aging mother, Janet Cochran, to move in with her and her 20-something adult children. Janet would become a co-owner of Cochran’s downtown Toronto house. “We lived two very different lifestyles, my mother and I,” Cochran says from her century home. “I’m a very urban downtown person. She was a suburban person.”

Cochran’s house was already subdivided into four apartment-style units with kitchens and baths. But she decided to take her mother’s apartment “right down to the studs,” renovating the space to include a kitchen, study, two bedrooms and bathroom to Janet’s “exact standard.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

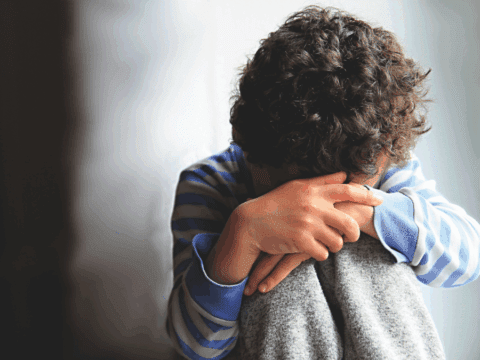

Still, the living situation isn’t without its hiccups. Such is the case when you start sharing a roof with your parent again after a nearly 50-year hiatus.

“It brings its own unique pressures. Suddenly I was living with my mother, and even though we have separate apartments, you have to adjust to those things,” the retired CBC producer says. “People can go into co-housing with a rosy view of it, [but] it’s not easy.”

Cochran’s home currently accommodates her 32-year-old daughter and her partner on the third floor, her 91-year-old mother on the second floor, herself on the main floor and her 36-year-old son in the basement apartment.

At the time her mother moved in, Cochran’s living arrangements were unusual. Today, multigenerational households — defined as dwellings containing three or more generations under the same roof — are on the rise.

In fact, multigenerational households are the fastest-growing family household type in Canada. According to Statistics Canada, as of 2021, 2.4 million Canadians, or 6.4 percent of the total population, lived in multigenerational households — a 50 percent increase since 2001.

While sharing space with three generations has always been more common among new immigrants and many eastern and Indigenous cultures, multigenerational living is now gaining traction across the cultural spectrum as financial pressures rise and our notion of the nuclear family shifts. Families who live in multigenerational homes point to benefits like cost savings and sharing household chores, but they also caution that the challenges can be abundant.

More on Broadview:

As multigenerational living grows in popularity, it’s important to better understand where the growth is coming from. For example, it’s primarily occurring in Canada’s major cities, reflecting the increasing number of new immigrants concentrated in large urban areas as well as the higher costs of downtown living.

Many First Nations and Inuit also live in multigenerational households, due in part to cultural preference. But financial savvy and the overall shortage of adequate and suitable housing are factors too.

“For some people — particularly those from cultures where multigenerational households are more common or even the norm, such as among some newcomers and Indigenous families — there would be positive connotations, as it can facilitate intergenerational support,” says Nathan Battams, a communications specialist at the Vanier Institute of the Family, which published its own report analyzing the growth of multigenerational households.

However, for those who weren’t already accustomed to living intergenerationally, the trend is growing amid mounting financial pressures. Rising inflation, combined with stagnant wages, is creating a financial imbalance that many Canadians are struggling to overcome.

Finding affordable housing for rent or purchase has also become a nightmare for many. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation reported that the rental vacancy rate across the country in 2023 was 1.5 percent, a record low. At the same time, average rents spiked by eight percent compared to the previous year. The aggregate price of a home in Canada, which is an adjusted median of all home types, rose to $815,500 in the third quarter of 2024, according to the latest Royal LePage House Price Survey.

“Canada’s cities are notoriously expensive places to buy or rent a home,” says Battams. “There’s a strong financial incentive to share a roof with multiple generations. For some, it might not be much of a choice.”

Cochran agrees. “I’m a single person, and to stay in this house would become impossible if I didn’t have [support],” she says. “For instance, rent coming in and vice versa. My kids couldn’t possibly find housing for the cost of the housing that we’re able to offer them.”

For Cochran’s mother, Janet, living with family saves money. After a fall in October 2023 that shattered her femur, the family installed a stairlift to help her reach her second-floor unit. But those expenses are “a fraction of what it costs to have somebody in care,” says Cochran. “She can now age in place in her apartment.”

Splitting the cost of living also provides Cochran some additional support. “It allows us to live affordably, and therefore I can take off and go on a vacation and someone will watch over my house and my dog…so it works in so many ways,” she says. “The financial benefits are really good.”

Beyond making ends meet, cultural apprehensions that once cast a shadow over multigenerational living in North America are shifting, says Battams. “There isn’t the same kind of stigma associated with living in the parental home well into young adulthood as in previous generations. This is largely just because it’s increasingly common.”

According to a 2022 Pew Research Center report, 56 percent of adults in multigenerational households in the United States say living with adult family members has been at least somewhat positive, though the assessments skewed more positive among higher-income respondents.

Pedrom Nasiri, a doctoral candidate in the University of Calgary’s sociology department, says multigenerational living is on the rise because Canadian perceptions of family structure are shifting. The concept of a nuclear family, consisting of two parents and two children, is not as important nor universal as it once was, Nasiri says.

“If we maintain this familial myth about a nuclear family that was maybe only around for a short period of time, we miss out on that multidimensional existence that Canadians are engaging in when it comes to constructing their families and households,” Nasiri says.

Cochran says that shift is far from complete, as the stigma that young adults are failing to leave the nest is alive and well. “The nasty take on it is always, ‘Oh my God, the kids can’t move out, why don’t they move out?’” she says. “Which I just think is not understanding what’s happening around us.…The positive way of looking at it is that you can take a house that you’ve lived in as a family and find ways to rethink it.”

Reimagining nuclear families also means rethinking the traditional roles of its members. Rania Tfaily, an associate professor with Carleton University’s department of sociology and anthropology, says the nuclear family model is “not working for a large number of people,” noting that it places heavy burdens on individuals, especially women, who are often working long hours while also caring for other family members.

Cochran’s family divides the household tasks, including mowing the lawn, cleaning, gardening, caring for pets and carrying Janet’s groceries up to her unit when she has them delivered. “It means we can run a fairly big house, without it being too much of a weight on any one of us,” Cochran says.

“My mother always [said] to me that the nuclear family isolated within itself is a relatively young form of family,” she says. Janet’s father died before she was born, so she grew up with her mother and grandparents. “What we’re doing echoes previous generations’ efforts at housing themselves,” Cochran reflects.

While living in extended families can be a blessing, tensions can easily arise. “It just takes some work, not just to get the kinks ironed out,” Cochran says, “but also to figure out who’s going to do what.”

And it takes flexibility. For instance, Janet was an avid gardener — until she broke her leg. After that incident, the family had to figure out who would step up to tend the yard, under Janet’s guidance.

Family dynamics aren’t the only hurdle for multigenerational living. Canada’s housing market isn’t exactly friendly to extended-family households, Cochran says. “We design condos that are 600 or 700 square feet,” she says. “Everybody’s atomized in these tiny little places you can’t possibly grow and expand in.”

In 2023, the federal government offered some support to people who want to live with extended family. It introduced the multigenerational home renovation tax credit, which can provide families with up to $7,500 to assist with the cost of adding a secondary unit to their home.

But that amount is unlikely to cover all of the costs. “I doubt this would help much for families that are sharing a roof because it’s all they can afford,” notes Battams of the Vanier Institute. “They would need to have enough money to renovate.”

Other families are rethinking the idea of multigenerational living in novel ways. Architect Joe Lobko and his wife, Karen, have lived in east Toronto in a three-storey, five-bedroom home for 30 years. They raised their kids and then became empty nesters. “We have more room than we need,” Lobko says.

After the City of Toronto approved the construction of laneway homes in 2018, Lobko took up the challenge in their backyard, creating plans for a two-storey, 900-square-foot home that is currently wrapping up construction. Lobko and his wife will move in upon its completion, allowing them to rent out the larger residence.

But the project goes far beyond Lobko and his wife; it’s a legacy project for their daughter, who is in her mid-30s and renting an apartment in west Toronto. Even if his daughter decides against having a family when she inherits the house and secondary dwelling, she’ll have a rental property that can serve another family’s needs while providing her with additional income.

To Lobko, multigenerational housing and rental housing can often be interchangeable, serving different needs at different times. That’s one of the reasons he believes multigenerational households are here to stay.

In stark contrast to 17 years ago, when she first bought her home, Cochran sees snowballing interest in intergenerational living, while Lobko says he’s seen dwellings like his pop up all over his neighbourhood.

It’s a new way of living. And while many Canadians are being economically squeezed into multigenerational houses, the trend can also encourage new ways of thinking. “People adapt,” Cochran says, “and then people’s ideas change.”

***

Janson Duench is a freelance journalist studying journalism and humanities at Carleton University in Ottawa.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2025 issue with the title “Under One Roof.”