A decade ago, two clowns were standing in a hospital hallway, about to meet a young girl who lost her leg in a boating accident. The four-year-old had recently received a prosthesis, so Helen Donnelly and her clowning partner, Jamie Burnett, hatched a plan to make her feel better about the experience.

Donnelly and Burnett, a.k.a. Dr. Flap and Ricky, went into the girl’s room and asked her if the two of them looked okay. “We’re about to meet Leg for the first time, so we want to look our best,” said Dr. Flap. After the little girl made some suggestions for how they might straighten up a bit, the two clowns knelt down and talked directly to the leg: “Hello, Leg! I like pizza, and I’m wondering if you like pizza?” In response, the little girl started animating the leg, playing along by answering back in character. “We managed to [take] something potentially awkward or stressful,” says Donnelly, and turn it into a moment of play. “To me, that’s the magic of clown.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Donnelly is one of Canada’s key champions for the therapeutic clowning community, bringing her red nose into hospital rooms and eldercare facilities, and pushing for greater recognition of a skilled and undervalued profession. Contrary to popular impressions, healthcare clowns don’t typically wear wigs or greasepaint. Nor does their work involve an ad hoc combination of over-size shoes and physical thrashing, moving from ward to ward in an attempt to elicit big laughs from prostrate patients. Therapeutic clowning is actually closer to a well-calibrated dance, balancing the divergent needs of patients and knowledge of the medical environment with the importance of consent, family dynamics and the psychology of being sick.

More on Broadview:

- How this family farm illustrates Canada’s vulnerable food system

- More older women are drinking too much. A new sobriety movement aims to help.

- Why it’s time to let native plants shine over lawns

Therapeutic clowning is fairly widespread in much of the world, though levels of professionalization can vary significantly in different countries. Canada’s oldest program, which started in 1986, is at Winnipeg’s Children’s Hospital, but there are also programs at Toronto’s SickKids, BC Children’s Hospital and Alberta Children’s Hospital.

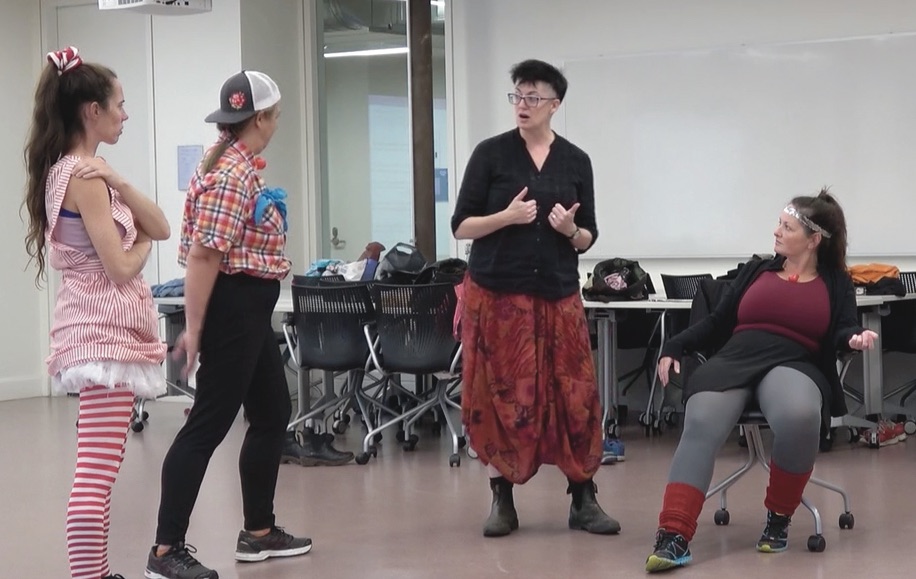

In fall 2018, guided by Donnelly, Toronto’s George Brown College kicked off a certificate program in therapeutic clowning — the first of its kind in North America and only the second in the world. Intended to run every three years, this new program formalizes protocols and bolsters respect for an often misunderstood vocation. It was a milestone achievement for Donnelly, the culmination of years of work and advocacy. But in June 2019, as the first class of students celebrated their graduation, her life took a devastating turn: she was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, an incurable blood cancer. Despite chemotherapy and stem-cell transplants, her remission was brief, and last fall, she learned she has only months to live. “It’s impossible for me to articulate just how much I’m mourning right now,” she wrote in a Facebook post in late October. “Seeing my professional life as a fool wind down is heartbreaking.”

Over the course of more than two decades, Donnelly has blazed a trail like few others. She found her own way into clowning after attending theatre school at the University of Toronto. Attracted by the physicality of performance, she signed up for classes in the Pochinko method, named for the celebrated Canadian clown Richard Pochinko, and eventually toured the United States, England and Brazil with Cirque du Soleil. She also served as the resident clown of Circus Orange, based in Hamilton, for 10 years. Alongside her circus work, Donnelly taught clowning students and created independent theatre projects, “mostly one-person musicals in clown gibberish.” And she has been active in therapeutic clowning since 2004.

The motivation of therapeutic clowns varies, but for some it’s a childhood brush with the healthcare system. When Donnelly was five, she was bitten in the face by a dog. She needed reconstructive surgeries to repair the damage, but she remembers her stay in Hamilton’s McMaster Hospital as positive. “I got so much attention, and who doesn’t love attention?”

Decades later, Donnelly clowned at SickKids for two years before moving to the Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital in 2007, where she worked as Dr. Flap. “That’s been a true joy,” she says, a way to share her art with a completely different audience. “They didn’t pay to see you, they’re not anticipating seeing you….So you’re always seeking permission [and] an opportunity to connect in a really profound way.”

Therapeutic clowning advocates describe the work as a studied, healing art — really, the merging of art and science. These clowns are trained to engage with vulnerable patients in evidence-backed ways to help reduce isolation, pain and stress. Both academics and healthcare practitioners have explored the benefits of therapeutic clowning, including the importance of laughter in anxiety reduction; the connection between humour and quality of life; and the role of music and non-verbal communication in stimulating cognitive function. A 2016 paper in Europe’s Journal of Psychology observed that clowns reduce anxiety and stress for both patients and family members. And a 2017 Israeli study found that children undergoing physical examinations experienced shorter discomfort when a medical clown assisted. Further, 94 percent of pediatricians reported that the clown’s presence improved their ability to perform a complete exam.

Bernie Warren, professor emeritus of drama at Ontario’s University of Windsor, has published widely on therapeutic clowning and led training sessions all over the world. He says the commonalities of therapeutic clowning across cultures and practices come down to this: “Medical staff work with the parts of the person that are sick; clown doctors work with the rest.” Both Warren and Donnelly describe therapeutic clowns as an integral part of the healthcare team. “The most successful programs [have a] flow of information between the healthcare staff and the clown doctors working on shift,” says Warren, whose hospital persona was Dr. Haven’t a Clue.

Donnelly says that many programs, including Holland Bloorview’s, grant clowns full access to each patient’s chart; the clowns document what transpired during their visit, leaving notes for other clinicians. “It’s a way of staying connected to each other, updating the progress the patient is making,” says Donnelly. “It’s best practice at work.”

She recalls one visit with a young refugee girl with an eating disorder. After consulting the patient’s file, Donnelly and her partner developed a plan to engage her in a pretend picnic. “We proceeded to mime items from an imaginary basket, sniffing them, tasting them,” says Donnelly. “We passed her an ‘apple,’ and she chomped into it!” The girl went on to describe her own favourite foods, a small breakthrough the clowns later recorded in her chart.

Clowns “can’t treat a broken bone. They can’t prescribe drugs,” says Warren. “But they work with the patient and the staff to encourage the body to heal itself in some ways.”

A big part of their role is helping patients feel more control over their situation. “Because you go to a hospital, and you lose all of your ability to do things for yourself,” Warren says. “You’re told when to eat. You’re told when you sleep. Your clothes are taken away and you wear this outfit that, unless you’re an exhibitionist, you don’t really want to wear.”

In grappling with her own illness, Donnelly has experienced the same identity shift she attempted to relieve in others. “There’s a sense of surrendering,” she says. “You become a patient, and that is your new job.” Society expects sick people to act sick, and we have specific ideas about what that means. Some level of mourning or reflection is considered normal; cheerfulness and silliness, less so. But therapeutic clowning works to expand the experiences available to those undergoing treatment, to acknowledge the full person beyond the hospital bed.

It’s a gross oversimplification to suggest that therapeutic clowns try to make people laugh. The point, says Donnelly, is to make a connection — but she also emphasizes the more pragmatic aspects of her work. She might playfully distract a nervous child who needs blood drawn, bringing out a “big and bright and silly” syringe or making up songs about how she wishes she were getting the needle instead. She has circulated in complex care units, where patients are on breathing machines, and where she has to depend on movement, music and miming instead of verbal exchanges. In the brain injury unit, she knows to slow down, keep her sentences short and create enough space between statements to allow the meaning to sink in.

Therapeutic clowns tend to work with certain populations of patients — in particular, children and the elderly. Warren says that this narrowing largely comes down to available resources and perceptions of clowning work. “People perceive that clown work should be done with children, and so money is found for that,” he says. “They don’t find money for people in adult cancer wards. Clowning in that context is perceived as inappropriate.”

Warren says that some of his best work as a clown was done in a palliative setting in Windsor, Ont., working with Dr. Charmaine Jones, whom he describes as a “visionary” in hospice care. He recalls one of his first gigs in that environment, heading into a room where a patient’s whole family was present: “I told Charmaine, ‘I’m very apprehensive. Should I be very quiet?’” She told him this woman was probably going to die in the next two or three days, and to be as big and loud as he could. He went in like a circus clown and did backflips. “The walls were almost vibrating from the laughter,” he says.

Clowns are increasingly being dispatched to work with veterans and those in eldercare settings, and Donnelly’s work with dementia patients has focused on legitimizing their participation and recognizing their wisdom. “You’re dealing with clients who have had full lives,” says Donnelly, with relationships, careers and families. “In spite of dementia, they have so much to offer.”

She and her clowning partner might ask a dementia patient to weigh in on a jokey argument they’ve been having, like whether to wallpaper or paint the room. With children, the clowns typically wear lab coats and wield toy stethoscopes. But with dementia patients, they don clothing and use music from the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, a touchstone to memories more likely to be intact. Donnelly’s elder clown is named Kat, modelled after the actor Katharine Hepburn.

Donnelly is starting to see an increasing number of clowning programs serving adults with cancer — a development she welcomes. “Many times I wished I had a couple of idiots to help me pass time in a waiting room,” she says.

But not everyone is warm to this kind of diversion. Some patients have a genuine fear of clowns, and others may not be in the right mood. Donnelly says that asking consent in her work is paramount. In addition to reviewing files and consulting with medical staff, therapeutic clowns are constantly seeking permission and scanning for cues that indicate whether patients want to engage, prefer to watch or would like to be left entirely alone. If they don’t want to play, “we will just move on to the next client,” says Donnelly. She still views it as a win “because they’re able to have agency.”

When she started out at SickKids, Donnelly clowned on the seventh floor, for a mix of cancer, infectious disease and respiratory patients. She was gowned and gloved, working solo, and that’s where she had to learn to adapt her art to her circumstances. She says she did a lot of “hallway and window play.” But she missed having a fellow clown to help guide the play or to bounce frustrations off of at the end of a long shift. “It felt lonely and challenging and exhausting,” she says.

Working in pairs is a common standard in the therapeutic clowning world. In hindsight, it’s “the only way to go,” says Donnelly. “It’s a witness to the work, an opportunity to [give and get] feedback.” It also takes pressure off the patient. When one clown approaches a room, a patient might feel an obligation to respond, she says. “But if you have two clowns standing in your doorway arguing with each other, it sets up a choice. Are you interested? Are you looking up from your book? It really [ties] back to respecting their privacy and who they are.”

As Donnelly was looking to make a transition, a clown at Holland Bloorview, Jamie Burnett, was also tiring of working solo. “We became partners, and everything fell into place,” says Donnelly. (Author’s note: Burnett and I were acquaintances in university, which is how Donnelly’s work crossed my radar.) “He really taught me to dream big, to envision five years down the road,” she says.

In 2011, after three years of clowning together, Burnett died of cancer. As his health declined, he and Donnelly shared their desire to build a therapeutic clowning program, a way to train students to serve in health care in a safe, effective and compassionate manner — in other words, a vehicle for taking clowning seriously. The kernels of that idea became the program at George Brown.

She sees the program as an essential push to fully prepare therapeutic clowns throughout Canada. Unlike France, which has particular qualifications for clowns, most of Canada’s programs are less regulated. Training is typically done on the job, and Donnelly was increasingly uncomfortable with this informality in such a specific, often delicate context. “You end up with a well-meaning artist who knows very little about what their client has undergone in terms of their condition, their mental health and the family dynamics involved,” she says.

Donnelly spent three years producing a 200-page student handbook, and she sought out five mentors around the world, in France, Brazil, the United States, Scotland and Quebec. The first George Brown class comprised eight clown artists, who were introduced to the history of therapeutic clowning, medical environments, the lives and experiences of patients and caregivers, and bioethics. Their artistic training included the development of both pediatric and geriatric clown personas, how to work in a duo, and engagement techniques. Another significant theme focused on the emotional demands of clowning and how to practise self-care. Watching patients struggle can take a toll. “It’s really vital that we know what to do with our emotions when they come up,” says Donnelly.

After completing placements in two health-care facilities, the class graduated in June 2019, and all have since joined Red Nose Remedy, a not-for-profit organization founded by Donnelly to promote the education and employment of therapeutic clowns.

Angola Murdoch is a professional aerialist who graduated from the George Brown program. Like Donnelly, she spent some of her early life in the hospital, being treated for severe scoliosis. She recalls meeting a therapeutic clown when she was 12. “I remember everyone just talking around me,” says Murdoch. “But this clown didn’t even give the time of day to my mom. She was just talking to me like I was special and in control.”

Since graduation, Murdoch has been working as a therapeutic clown at several facilities, including Safehaven, a residential program in Toronto for youth with complex needs. (Some of Murdoch’s work has gone online during the pandemic, with video calls replacing in-person visits with patients.) She has been able to draw on both the artistic persona and theoretical techniques she developed at George Brown. “Our job is to listen to our clients and to make them feel heard and to make them feel in control and to make them feel joy, happiness and love,” says Murdoch. “We sing, we play ukulele and we use touch. A lot of these clients are only being touched to have medical procedures happen. And so we hold people’s hands. We touch their faces. And when we leave, we always ask if it’s okay to come back, and we’ve never had anyone say no.”

In November, Donnelly marked her permanent retirement from Holland Bloorview with an emotional farewell party on Zoom. While she’s confident that the work will continue without her, she still has much to teach the clowns in her orbit. She has been handing the reins to other clown performers, and plans on “passing her nose” to Derek Kwan, executive director of Red Nose Remedy. “She has run so much of it herself for so long,” says Kwan, who has worked as a therapeutic clown in both Canada and Taiwan. “A lot of this is just downloading her brain and trying to understand her vision for the future. It’s delicate because it’s a lot of saying goodbye.”

Kwan says that the fate of the George Brown program is unknown, but he hopes Red Nose Remedy can “grow [in] size and scope all over Ontario to include multiple populations (pediatrics, elders, others) and also to serve as a hub for the therapeutic clown community.”

In the time she has left, Donnelly is trying to balance her inclination for gratitude with her acceptance of drawing a short straw. Clowning friends from near and far have circled around her and tried to keep her spirits up. “I just keep thanking my lucky stars that I chose a career that involves being a professional idiot and being partnered with a horde of idiots from around the world,” she says. “It’s just been so joyous and life-affirming.”

***

Sarah Treleaven is a writer and podcaster in Halifax.

This story was first published in Broadview’s April/May 2021 issue with the title “Bedside laughter.”

This article was a breath of fresh air