In the last year, if you were looking closely, you may have spotted two newspaper stories ostensibly about similar subjects. I’m referring to the story of the canonization of Brother André and the story announcing the arrival of goalie James Reimer in Toronto.

Brother André Bessette, the “Miracle Man of Montreal,” is credited with curing the illnesses of thousands of faithful followers before his death in 1937. Those celebrated cures were not, however, what lead to his canonization last October. To pass the test, one must be associated with two miracles post-mortem. The clincher for Brother André was the recovery of a Quebec boy from serious head injuries in 1999, but his first qualifying miracle occurred in 1958, when New York businessman Joseph Audino overcame terminal cancer after praying to Brother André.

James Reimer, “The Miracle Man from the Middle of Nowhere,” according to a newspaper headline, is a rookie goaltender from Morweena, Man., whose talent has to do with saving goals, not souls. Reimer was called up to play for the Toronto Maple Leafs just before Christmas, and he was actually pretty adept at keeping the puck out of the net.

For die hard Leafs fans, this was good news, but a miracle? Even if we make allowances for the hyperbole of newspaper headlines, it still seems that the word “miracle” has been demoted. In the Christian tradition, “miracle” is the name we give to extraordinary phenomena that are inexplicable by natural laws and so are attributed to the agency of God. But nowadays, if we win the lottery, it’s a miracle. If our teenager tidies up his room, that’s a real miracle, even though there’s no evidence God was in there matching up the orphan socks. “Miracle” is more likely to signify the merely surprising than the truly mysterious.

There’s even a mathematical law to this effect. British mathematician John Littlewood defined a miracle as an exceptional event occurring at a frequency of one in a million. Assuming humans experience events at one per second during waking hours, Littlewood determined that each of us would experience a one-in- a-million event every month or so. Miraculous events are therefore commonplace, he argued.

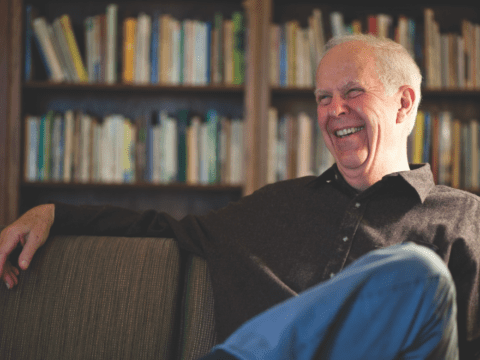

Dr. Robert Buckman is an oncologist at the Princess Margaret Hospital in Toronto who describes himself as a non-religious humanist. Buckman hasn’t watched enough hockey to feel qualified to pass judgment on James Reimer’s miracle between the pipes. Miraculous cancer cures, however, are right up his alley.

Buckman devised and hosted a television series called Magic or Medicine? Broadcast on TV Ontario in the 1990s, the program invited viewers to write letters describing medical miracles they had experienced. Buckman’s team would scrutinize their claims, revisiting medical files and interviewing the specialists who had been involved in the cases. “We investigated every one — 20 in all — and there was a perfectly logical, rational explanation for every single one of them,” he says.

The most germane example might be the case of a man who believed he had stage 4 sarcoma of the leg, which had spread to his lungs. “He was told he was going to die, but he turned his life around and prayed faithfully, and he was completely cured,” Buckman reports. “That’s what he thought.”

“I looked at his CT scans,” Buckman says. “The evidence showed that this man had never had stage 4 sarcoma, and that no sarcoma had spread to his lungs. It was either a misdiagnosis at the time or a misunderstanding, but it was not cancer. Even so, the patient could not be convinced that his prayers had not saved him from certain death.”

The miraculous cancer recovery in 1958 that helped propel Brother André to sainthood may well have been a similar triumph of wishful thinking, Buckman suggests. Or it may have been spontaneous remission, which occurs in one in every 10,000 cases of cancer. “I don’t call these events ‘miracles,’ but in 1958, maybe,” he says, acknowledging the leaps in medical science over the last half-century. “A lot of what we attribute to divine intervention is simply what we don’t yet have a legitimate explanation for.”

Embedded in this simple assertion is a profound challenge. The essence of faith is to accept, and even to revere, that which cannot be understood. The essence of science is to strive to understand what is not yet understood. Viewed in this way, science seems determined to whittle away at faith by explaining the mysterious.

In 2003, Cambridge professor Colin J. Humphreys published his study The Miracles of Exodus: A Scientist’s Discovery of the Extraordinary Natural Causes of the Biblical Miracles. In it he explained that the miraculous parting of the Red Sea was caused by high winds. “I’ve done the maths and the calculations for what would happen with a hurricane force wind of 80 mph in the Gulf of Aqaba,” he said. “The water would be pushed out from the seashore and would create a wall of water about four or five feet tall and maybe 800 yards out to sea.” Pharaoh’s army found out what would happen when the wind died down.

Even the great miracle of Creation has had to endure some adjustments. For centuries, Christians believed the Earth was about 6,000 years old, but radiometric dating shows it’s actually been around for 4.54 billion years. The universe is three times older than that, but, incredibly, researchers at Cambridge University recently used light from a black hole to peek at what the universe looked like 13 billion years ago. How they did it, I’m not sure. But if they can do that, is anything inexplicable anymore? Or merely “as yet unexplained”? And what need is there for miracles in such a brave new world?

“When you find something as successful as science has been, there’s a danger of being idolatrous about it, to take that great success and say it must be everything. But that’s a leap, and it’s not justified,” says Robin Marjoribanks, a physics professor at the University of Toronto.

Marjoribanks’s parents were long-standing United Church members, but his own faith languished until a life crisis taught him that there are aspects of human experience where reason does not apply. “I’ve trained as a mathematician, and I don’t think rationalism is absolute,” he says. “As a scientist, there’s nothing that says my observations are complete or definitive.”

Marjoribanks challenges the idea that the term “miracle” has no place in the modern world. And he’s not referring to winning the lottery, adolescents behaving well or the Leafs making the playoffs. For him, the idea of a miracle as a “phenomenon inexplicably contradicting expectations or experience” is not inimical to science at all. “Scientists watch for contradictions, even seek them out, because that’s where deeper understanding often comes from,” he says, citing Isaac Asimov’s claim that “the most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not ‘Eureka!’ but rather, ‘Hmm. That’s funny . . .’”

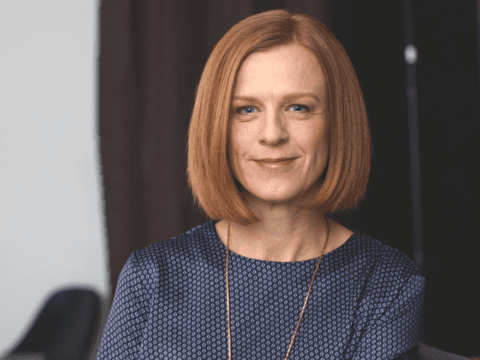

Ursula Franklin is an 89-year-old physicist, a professor emerita at the University of Toronto, a peace and women’s rights activist, and a practising Quaker. Like Marjoribanks, she cautions against putting too much faith in science.

“God made nature,” Franklin says. “Scientists have a conversation with nature, and the more a scientist understands of the language of that conversation, the more he or she also sees how much more there is to talk about.” Franklin says that the more sophisticated her own dialogue became, the more she sensed that some aspects of life cannot be captured in scientific terms.

For example, you can use math to analyze music, “but that is not sufficient,” she says, because it fails to describe “the joy you get, the feeling of revelation when you experience the totality of all these sounds integrated With science alone, you can’t say, ‘This is a moment of grace, this is blessed.’”

Joseph Audino, the man who prayed to Brother André and overcame cancer, must have experienced a moment of grace and blessing when the shadow of disease was lifted from his life. Who’s to say this was not a miracle? For Franklin, that personal capacity to believe is the key.

Ever the teacher, she imparts some advice: “Don’t create a false problem [by opposing science and faith], but rather point to the fact that the best science and the best faith can coexist in people. The rest is probably just huffing and puffing.”

As for the Leafs, they finished out of the playoffs again this year, losing their last game with Reimer in net. Next year, maybe they should call up Brother André.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2011 issue with the title “Too modern for miracles?”