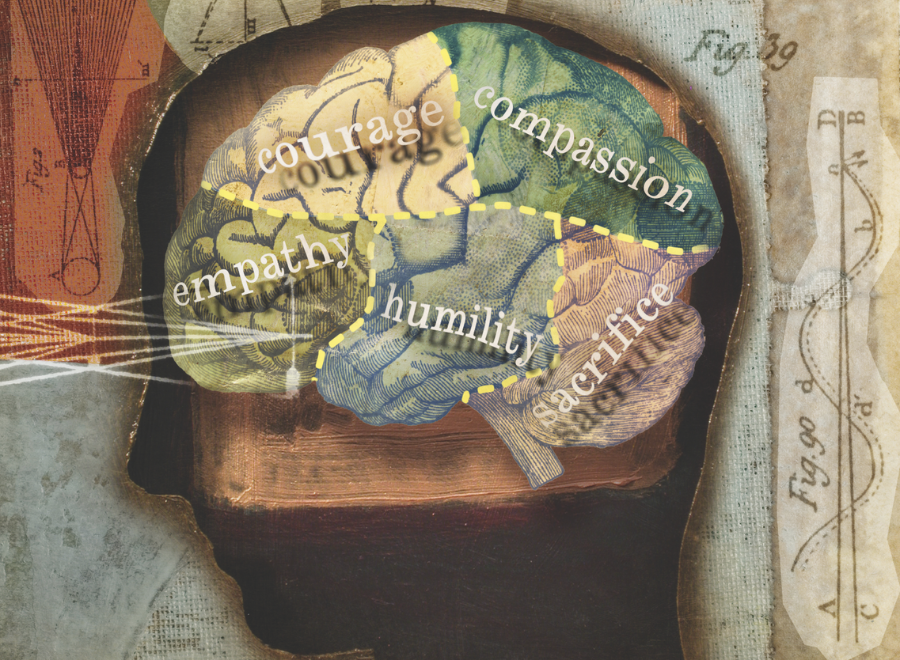

For many theologians and philosophers, the essence of morality is the awareness that other people’s needs are as important as your own — if not considerably more. In fact, this social consciousness reveals that, by and large, we’re not purely in it for ourselves. Despite the unseemly behaviour that human beings regularly unleash on each other, we are inherently empathetic creatures.

In recent years, neuroscientists have begun to illuminate this idea, tracing the evolutionary origins of empathy and uncovering the genes that dispose some individuals to senseless violence and others to acts of altruism. They’re offering an explanation for the pathologically selfish Bernie Madoff and the innately virtuous Mother Teresa, as well as the rest of us who fall somewhere in between. But their answers could pose a challenge to traditional religious views. To people of faith, such science threatens to reduce empathy to a mere physiological response — far from the mysterious interplay of forces thought to give rise to the human spirit. Still, whether we believe compassion springs from God or brain chemistry, empathy research promises to reshape our understanding of morality in coming years.

According to Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection, only the fittest of a species reproduce and pass their genes on to another generation. This incentive would seem to encourage competitive, self-interested behaviour at the expense of compassion. Yet surprisingly, empathy — and by extension self-sacrifice — happens all the time in the natural world, as Darwin himself observed. For social animals, “those communities which included the greatest number of the most sympathetic members, would flourish best and rear the greatest number of offspring,” he wrote in The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex in 1871.

Throughout human evolution, empathy is the “invisible hand” that inseparably binds us, argues ethical prophet Jeremy Rifkin. In his 2010 book, The Empathic Civilization: The Race to Global Consciousness in a World in Crisis, he describes the history of humanity in terms of ever-expanding empathic borders, from the blood ties of hunters and gatherers to our current age of growing transnational consciousness. “When we say to civilize, we mean to empathize,” he writes.

Today, research is showing how this “invisible hand” is inextricably stitched to our neural patchwork. In other words, we are genetically hard-wired to experience another’s plight as if it were our own. In its simplest expression, when one baby cries in a nursery, others invariably do also. When most people witness someone else’s suffering or read about a murder or assault, their palms perspire and their blood pressure sharply increases.

When this happens, areas of the brain that are more than 100 million years old, such as the limbic system, are actively engaged, according to Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University and the director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center in Atlanta. Empathy begins with “the synchronization of bodies,” he says — the sweaty palms, the rising pulse. We experience it first as a physical response, “not in the higher regions of imagination, or in the ability to consciously reconstruct how we would feel if we were in someone else’s shoes.”

As de Waal points out in his 2009 book, The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society, “We aren’t Robinson Crusoes, sitting on separate islands; we’re all interconnected, both bodily and emotionally. . . . Members of the species Homo sapiens are easily swayed in one emotional direction or another by their fellows.”

There is even evidence that empathy is present in highly social mammals, such as dogs, elephants and of course other primates. For example, chimpanzees show consolation: they embrace, kiss and groom others who are distressed. De Waal, who was ranked among Time’s 100 most influential people in 2007, has collected thousands of examples of animal consolations, and found that the comforters are more typically females than males, as it is with human children.

Although genes tell us much about the roots of empathy, they’re not the whole story. De Waal says we are likewise influenced by the environments in which we grow up. Every experience throughout our lives can “modify genetic expression” — activating certain genes or switching others off — which, in turn, can set in motion new behaviours. In this way, “genes and environments intertwine.”

If you ask Paul Zak, the key to empathy lies with a 400-million-year-old neurochemical: a single molecule called oxytocin.

Zak is the founding director of the Claremont Graduate University’s Center for Neuroeconomics Studies in California. In 2004, after searching for a neurochemical basis for empathy, Zak’s laboratory discovered oxytocin — what he refers to as the “moral molecule” or the “love hormone.” Oxytocin is the social glue keeping families, communities and societies together, Zak writes in his new book, The Moral Molecule: The Source of Love and Prosperity.

He believes that oxytocin first forged the bond between mothers and their babies. It then became the neurochemical motivator for positive social behaviours: holding the door open for a stranger or picking up something dropped, even if your own hands are full.

Says Zak, “We found that positive social stimuli of many types stimulate the brain to release oxytocin, and when it’s released, the self-other divide melts a bit and we start treating strangers like family.”

He continues, “The existence of a moral molecule shows that we are a better species than sometimes we give ourselves credit for. In a real biological sense, we are one big human family: we have the potential to care about nearly everyone on the planet. . . . As it’s written in Galatians 5:14: ‘You shall love your neighbour as yourself.’”

Zak, a “hopeful Christian” whose mother is a former Catholic nun, confesses to being enthralled by churches — St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome brought him to tears. He’s conducted several oxytocin experiments in places of worship and claims that religious rituals cause oxytocin release in about 60 percent of participants. Such rites endure because they “bring us closer to others — and perhaps closer to our loving selves,” he says.

Zak adds that the “highly empathic personalities” of Mahatma Gandhi and Mother Teresa likely released more oxytocin than most. “These moral exemplars had crises of faith and purpose like most of us do, but for much of their lives, they loved even those whom others thought to be unlovable.”

In another series of studies at Zak’s laboratory, when oxytocin was administered by nasal spray, it reportedly heightened trust and co-operative behaviour within social groups. The upshot? Researchers are convinced they will soon be able to cultivate empathy in human beings pharmacologically.

“To understand how something works is also to begin to see ways to modify and even control it,” says Guy Kahane, deputy director of the Oxford Centre for Neuroethics and the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics. “We can try to understand how the heart works from a purely theoretical perspective, but this knowledge would also be of immense use to doctors trying to treat heart disease. In the same way, our growing — though still rudimentary — understanding of the way our minds work will inevitably suggest ways to influence our minds or even directly tinker with our brains.”

Kahane points to sex offenders taking anti-androgen drugs to curb their libido and students using Ritalin to focus in school. In like manner, he says, we will eventually “influence our emotions, attitudes and behaviour by making ourselves more motivated to actually act on our moral principles.”

The idea of a morality pill calls to mind A Clockwork Orange, the Anthony Burgess novella adapted to film by Stanley Kubrick. The story sees an unrepentant psychopath, Alex, programmed by the state to respond with nausea to violence and sex. What makes us human, the narrative suggests, is our freedom to choose both good and evil, and for society to force individuals into righteousness is as sadistic as the actions of Alex himself.

Kahane acknowledges the story’s Christian theme but takes exception to the message: “Many believe that if you’re coerced to be good, then you’re not really good, and the act of forcing you in this way might itself be deeply immoral. But we punish people all the time. We coerce them. Secondly, the psychopath in A Clockwork Orange freely chooses to undergo treatment. . . . So it’s hard to see how [drug-induced moral improvement] will reduce our freedom.”

Still, the ability to choose to resist apathy is something precious, Rev. Ambury Stuart argues. “[Empathy] is not a broken clock that scientists should simply fix.” Stuart, of Toronto, was a meteorology scientist for more than 30 years before being ordained as a United Church minister in 2004. “Free will is the great gift of our consciousness, although also a source of great suffering,” he says. “If we didn’t possess free will, we simply wouldn’t be capable of grace. . . . If we limit ourselves by manipulating body chemistry, we become limited in a way and certainly far less human.”

He agrees with another scientist-turned-clergyperson, Rev. John Polkinghorne. The English theoretical physicist and Anglican priest has argued that “a world with a possibility of sinful people is better than one with perfectly programmed machines.” While scientists are keen to study and tinker with almost everything, the human spirit is not something they can ever measure empirically and eventually manipulate, Stuart says. It’s “purely a concept and principle of faith.”

He continues, “In the beginning of the modern era, it was believed that science would answer everything about the fundamental processes of life. That was the consensus. But the 20th century proved to be the great implosion of that hypothesis. It even brought us atomic weapons and pollution, among other things. . . . Science definitely has limitations; eventually its practitioners hit a proverbial wall.”

Stuart echoes the sentiments of Albert Einstein, who cautioned that we should be careful “not to overestimate science and scientific methods when it is a question of human problems.” The famed physicist also weighed in on empathy, noting in 1954 that “our task must be to free ourselves . . . by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

While they may differ on the means, both scientists and the faithful can agree that it’s high time for humanity to transition from the kind of me-first culture that provoked the global financial crisis and its ongoing aftermath. If we can harness our innate empathic sensibility to harmonize the planet’s many relationships, as Jeremy Rifkin proposes in The Empathic Civilization, we will move beyond our “detached, self-interested and utilitarian” mindset into an entirely new era.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s November 2012 issue with the title “Decoding our good side.”