CONTENT WARNING: This article contains descriptions of murder, sexual assault and child sexual abuse. Please take care when reading.

A mid-July afternoon last summer found Rev. Bri-anne Swan navigating the ribbon of asphalt that connects the Texas prison towns of Livingston and Huntsville, under a fierce sun that would push the thermometer to 40 C.

Swan had spent the earlier part of the sweltering day in Livingston, meeting with a man on death row and members of his family. His name was Ramiro Félix Gonzales. He was the same age as Swan, 39, and had spent the past 16 years in solitary confinement after pleading guilty to kidnapping, raping and murdering Bridget Townsend, an 18-year-old woman from Bandera County, Texas, in 2001, when he was also 18. A jury sentenced him to death by lethal injection in 2006, but a series of appeals and other legal actions had repeatedly delayed his execution date.

But now it was imminent. In 48 hours, Gonzales would be loaded into a Texas Department of Criminal Justice vehicle and driven 70 kilometres to the state prison in Huntsville, where Texas sends condemned prisoners to die.

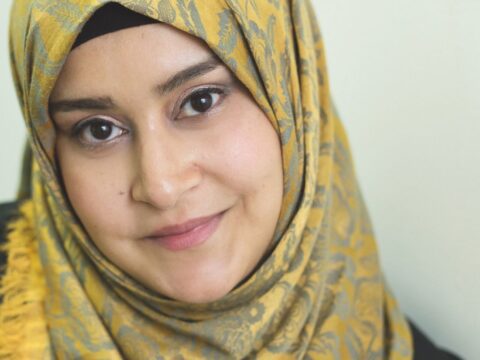

Swan, who lives in Toronto with her husband and two sons, is a longtime opponent of capital punishment. She chanced upon Gonzales in 2014 through a website where death-row prisoners advertise for pen pals. In the years that followed, Swan developed a close long-distance friendship with him.

While she abhorred Gonzales’s crime, she also abhorred the idea that the state would kill him as punishment. She had come to believe that Gonzales had undergone a profoundly positive transformation in the years since he murdered Bridget Townsend.

In 2021, Swan was commissioned as a minister in The United Church of Canada, and her relationship with Gonzales became professional as well as personal, thanks to a U.S. Supreme Court ruling that gives condemned prisoners the right to choose a spiritual adviser to accompany them as their sentences are carried out. It was in that role that Swan braved the aggravations of pandemic air travel and flew to Texas before Gonzales’s execution, scheduled for 6 p.m. on Wednesday, July 13.

While visiting with Gonzales on July 11, Swan and the condemned man discussed how she would serve communion in his holding cell before his execution. During the visit, she also received word that officials in the Texas criminal justice department wanted to meet with her on the morning of the execution. She took it as a sign that the execution would go ahead as planned. Further confirmation came later, as she set out to drive back to Huntsville, when she learned that the Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles had denied Gonzales’s request for clemency.

Behind the wheel, Swan mentally composed the prayer she would offer as Gonzales breathed his last. She thought about his family, and she thought about Bridget Townsend and her family. She thought about what she would wear to the execution — her clerical collar, for sure. As the person responsible for Gonzales’s remains, she thought about what to do with his ashes when it was all over.

“It was a lonely drive,” she later said. “I stopped for gas, and after I filled up, I got back in my car and actually sat there…thinking about the number of times I’ve driven that route back and forth between Livingston and Huntsville, and how that’s the same drive Ramiro would be taking. And I thought, at least it’s a pretty drive. I hope he can see out the window.”

Swan was almost back at her motel in Huntsville when her phone rang. She could see it was one of Gonzales’s lawyers, who advised her to pull over. The connection was bad, and she couldn’t make out what the lawyer was saying — except for one word. But that single word pulsed with ethical, emotional and, for Swan, spiritual consequence. “I was shaking. Not just my hands but my whole body — that feeling when you’re violently shivering but it’s not because you’re cold.” She remained on the side of the road until it felt safe to drive again.

A week before Gonzales was scheduled to die, I met with Swan in a downtown Toronto coffee shop. She seemed more anxious than I’d seen her before. It had been two weeks since she’d returned from Texas and a crash course in execution orientation she was required to attend as Gonzales’s spiritual adviser. A judge had ruled that Swan should be allowed to hold Gonzales’s hand as he died, but other 11th-hour legal issues remained up in the air. Her phone kept alerting her to incoming messages, but none were from the lawyers labouring to secure Gonzales a reprieve.

Reminiscing about her roots seemed to lighten Swan’s mood. She described growing up on a farm near Moonstone, Ont., about a 90-minute drive north of Toronto. The Swans were a churchgoing family, members of Eady United. Rev. Linda Butler, a minister at Eady when Swan was a Sunday-schooler, recalls her as “being quite a serious young girl, relatively quiet and, right from the beginning, extremely nurturing.”

In high school, Swan befriended twin sisters who were activists. Swan was a charter member of the club they started and named “In Our Small Way.” The club promoted causes like anti-racism and environmental justice, organizing fundraisers to boost awareness. Swan also joined Amnesty International letter-writing campaigns against capital punishment.

She graduated in 2001 and moved to Toronto, working at various office jobs while figuring out what to do next. A career in academics was a possibility. So was becoming a professional singer-songwriter. Swan had dabbled in music since teaching herself to play the guitar as a youngster. She’d performed for school assemblies, at seniors’ centres, at events like White Ribbon campaign rallies — and at the church in Eady. “The congregation sat through rather a lot of terrible performances,” she quipped.

Swan was 18 when she left home to begin the next chapter in her life. It’s not lost on her that she was the same age as the killer and his victim when Ramiro Gonzales murdered Bridget Townsend — and that they all shared a rural upbringing. “You know,” she said, “Moonstone’s not so different from Bandera.

The scant information that exists about Bridget Townsend paints a picture of an outgoing, generous young woman from Bandera County, Texas, who was studying to be a nurse but had fallen into bad company. Bridget was the youngest of Patricia Townsend’s three kids. “She was one of the sweetest, kindest, most gentle children you’d ever know,” her aunt Clara Kunkler told the San Antonio Express-News in 2005. “Any time she saw an elderly person she’d say hello. She could never pass a newborn child without saying hello. She was always giving people gifts.”

On the evening of Jan. 14, 2001, Townsend was alone in the trailer of her boyfriend, Joe Leal, a drug dealer. The phone rang. It was Ramiro Gonzales, whom she had known since middle school. He was high on cocaine and looking to score more drugs. Hearing that Leal wasn’t home, Gonzales drove to the trailer, pushed his way past Townsend and began scouring the place for drugs and cash. When Townsend tried to call her boyfriend, Gonzales pushed her into a bedroom and tied her up. He then marched her out to his truck and drove to the ranch where he lived with his grandparents. He grabbed a deer rifle, got back in the truck, drove to a remote location in the brush and forced Townsend to walk toward a wooded hillside.

The terrified woman offered Gonzales anything he wanted — money, drugs, sex — if he’d spare her life. He took her back to the truck and sexually assaulted her. Then he walked her to the brush and shot her.

Her remains would not be found for two years. In 2002, Gonzales pleaded guilty to kidnapping and raping another woman and was sentenced to life in prison. Soon afterwards, he told the Bandera County authorities that he had information about Bridget Townsend and could take them to her body. The sheriff and Gonzales, accompanied by a Bandera County jail official, drove to the site in neighbouring Medina County where Gonzales said he shot the young woman. There they found a human skull and other remains, as well as the jewelry that Gonzales had told them Townsend was wearing when he killed her.

Gonzales at first tried to deflect full blame for the murder, but eventually he confessed that he was solely responsible. A trial in 2006 found him guilty of capital murder.

Since 1976, Texas has accounted for more than a third of all executions in the United States. Texas law requires prosecutors seeking the death penalty to show that a person convicted of capital murder has a high probability of reoffending, even while serving a life sentence in prison. The standard is called “future dangerousness,” and the prosecution at Gonzales’s sentencing trial produced psychiatric testimony suggesting that Gonzales more than met it — he was the “worst of the worst.” The jury agreed and condemned prisoner number 999513 to die.

Gonzales later claimed it was remorse over the anguish he caused Bridget Townsend’s family that led him to confess to killing the young woman. Swan discerned genuine remorse and a longing for redemption when she came across his online pen-pal profile, and later in their first exchange of letters. “I wish to speak to your heart as a person,” he wrote, “in the hopes that you would give me a chance to bring before you the person that I really am.”

By the time the two began to correspond regularly, Swan was pregnant with her second child and studying to be a psychotherapist after several years of gigging as a singer-songwriter. Gonzales was into his eighth year of solitary confinement on death row in Livingston. Alone in his cell for 22 hours a day, in a prison one writer described as “the most lethal [death row] anywhere in the democratic world,” Gonzales had taken up yoga and drawing, embraced religion and obtained a degree from a Christian college. He expressed his new-found faith in sermons he wrote for the prison radio station.

Swan kept her busy letter-writing relationship with Gonzales mostly under the radar until the Toronto Star caught wind of it and published a 2,300-word article headlined “My friend on death row” in September 2016. Gonzales’s execution had been set for August, and he had asked Swan to be a witness. The execution was postponed, but she journeyed to Texas anyway, travelling mostly on her own dime, with help from a fundraising concert she gave at Rosedale United Church in Toronto.

She came home from the trip — the first of four she would make to visit Gonzales ahead of last July — steadfast in her belief that he was no longer the brute that prosecutors made him out to be. “I have no qualms about saying, that in 2022, Ramiro is a good person,” she said last spring. “I would not feel unsafe around him without the glass separating us. Do I think he should be released into the world? No. Nobody is advocating that. Only that the state not kill him.” Well aware that her views angered those who believed Gonzales should die for what he did, Swan shunned the spotlight after the Star article appeared, keeping a low profile even as the execution approached last summer.

Texas has a long history of executing convicts who were teenagers when they committed their crimes. The majority have been Black and Latino. Gonzales was 71 days past his 18th birthday when he killed Bridget Townsend — just over the threshold for executions set by the Supreme Court in 2005. Critics, including the American Bar Association, contend that the threshold of 18 years fails to reflect research showing that key regions of the brain do not develop fully until later in early adulthood. This, coupled with the failure of Gonzales’s court-appointed attorneys to enlist mitigating expert testimony about the effects of trauma he experienced in childhood, as well as the possibility he suffered from undiagnosed fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, confirmed for Swan and his new attorneys that the death sentence was patently unjust.

The details of Gonzales’s early life are extremely disturbing. His 17-year-old mother had been a victim of childhood sexual violence. She abused drugs and alcohol and sniffed paint fumes while pregnant with Ramiro, trying twice to abort the fetus she carried. She vanished after she gave birth, leaving the infant to be raised by his grandparents. The manager of the ranch where he lived remembered Gonzales being grossly neglected as a toddler.

When Gonzales was barely school age, a male cousin began sexually abusing him. Adults at the ranch would get drunk and beat him, with no consequences. When he was 12, a 19-year-old woman sexually assaulted him, resulting in the birth of a child. Around the same time, he began using drugs and alcohol. At 14, he was arrested for public intoxication after police found him on a bridge, threatening to jump. Many more run-ins with the law followed. He stopped going to school after Grade 7, his substance abuse spiralling after an aunt, described as his sole source of love and support, was killed by a drunk driver. By age 16, Gonzales was a full-blown addict. Mental health records suggested he was obsessed with death and decay.

I had never spoken to a murderer, much less a murderer condemned to die. I didn’t know what to expect when Swan arranged a telephone chat with Gonzales six days before his execution date. Earlier, I’d asked Swan about his emotional state. “It’s as positive as it could be for someone who’s going through his situation,” she said. “We are trying as best as possible to maintain hope while simultaneously treating this as if it’s going to happen.”

For a man who was going to be killed in less than a week, Gonzales was surprisingly buoyant. I did not detect fear or bitterness. Even discussing the deficiencies in his legal defence, he was forgiving. “I don’t think it was so much the legal team I had, although there were things they did not do or should have done. It’s the courts. The courts only allow you so much when it comes to funding for experts, investigations, mitigations — all those things.…Maybe they did the best they could with what they had.”

Gonzales was equally philosophical about the fact that he’d spent almost all of his adult life in solitary confinement. “The thing about this segregation part is you can’t go nowhere, you’re 24/7 locked up in a cage. And you’re faced with your own worst enemy — that’s you. You think about your regrets, the things you should have done, would have done, could have done.” Shouldn’t have done? I asked. “Sure,” he said, “shouldn’t have done.” Gonzales described how he’s taken to calling Swan “Mana,” a term of endearment derived from hermana, the Spanish word for sister; how Swan has made him feel that he’s part of her family; and how she’s become “a moral compass, a spiritual compass” who helps shape the decisions he makes simply by being a presence.

Prison life can irrevocably harden a person. Listening to Gonzales speak, I found it hard not to conclude that, improbably, he had risen above his circumstances. Fury had given way to empathy; introspection had overtaken impulse. “What I share with Bri-anne and my attorneys, all those who have been involved with me,” he said, “is everything I’ve learned about humanity, about the sacredness and sanctity of human life. Even I matter, despite my mistakes.”

He said if the execution were somehow not to happen, he could rationalize spending the rest of his life in prison “if I can do certain things — get into school, get a vocation and just basically spend whatever time I have in a real productive manner.…I’ve learned this one thing: freedom is not a place.”

Afterwards, I mentioned to Swan that I’d been surprised by Gonzales’s intelligence and thoughtfulness. That probably said more about me than him. I recalled something Swan said in an earlier conversation, about how she, too, had underestimated him. “I had this really flawed idea that I was just going to do this nice thing and write to him, without any openness to the fact that I might be changed in the process.…You don’t enter into a relationship with Ramiro without feeling profoundly moved.”

Swan thinks she “might have been in shock” as she tried to regain her composure at the side of the road on that hot afternoon in Huntsville last July. At the same time, but more than 2,000 kilometres away, Cantor Michael Zoosman was planning a vigil for Gonzales that would coincide with his execution. It would start with a traditional Jewish prayer for Bridget Townsend and feature a song chosen by Gonzales.

A chaplain at a federal hospital near Washington, D.C., Zoosman heads a Jewish organization dedicated to abolishing the death penalty. He had been trading letters with Gonzales when he mentioned that a member of his home congregation needed a kidney transplant. Gonzales “jumped at the opportunity,” says Zoosman. “He said he wanted to be able to give back life, the life he took, as a way of being right with his God.” The prisoner started a process within the Texas corrections system to donate a kidney for transplanting before he died.

The match didn’t work out, but with the clock ticking, Gonzales, Zoosman and sympathetic lawyers pressed ahead with a request to postpone the execution so Gonzales could donate a kidney. The effort caught the attention of the media, and with just days to go before his scheduled death, Gonzales was making headlines worldwide. Zoosman dismissed speculation that the bid to donate a kidney might be merely a delaying tactic. “I have had no doubt from day one that it was not his intention to stop the execution,” he told me.

More from Broadview:

- Christians need to grapple with their relationship to the death penalty

- This month’s incredible cover story was 6 years in the making

- Canada came through for me. Not so for Sacha Bond.

The vigil Zoosman planned never happened. The word that Swan managed to make out amid the hiccups of the bad phone connection with Gonzales’s lawyer was “stay” — as in, a stay of execution.

“I frantically disconnected my phone from the car system and called her back,” Swan recalled. The lawyer reported that the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals — the last viable line of defence between Gonzales and the execution chamber — was sending the case back for review to the county court that sentenced him. For the time being, the execution was off.

“It didn’t seem real,” Swan said. “I remember having both hands on the steering wheel and saying, ‘He’s not going to die. He’s not going to die.’ Over and over. There was no reason to hold it all together anymore.”

Gonzales’s attorneys had zeroed in on the 2006 finding of “future dangerousness.” The psychiatrist who had diagnosed Gonzales with anti-social personality disorder and declared him a continuing danger had based his assessment largely on data suggesting that sex offenders were almost certain to offend again. Legal scholars have since debunked the data as junk social science with origins in a single unsubstantiated claim in a 1986 article in Psychology Today magazine that inexorably worked its way up the judicial food chain to become a doctrine that swayed hundreds of thousands of cases.

“You don’t enter into a relationship with Ramiro without feeling profoundly moved.”

Rev. Bri-anne Swan

Numerous studies, including research commissioned by the statistics arm of the federal Department of Justice, have since shown that the likelihood of sexual offenders committing new offences is far lower than the rate cited at Gonzales’s sentencing. This is especially true for offenders who are young, as Gonzales was. In a petition to the court of appeal, Gonzales’s lawyers noted that the psychiatrist who testified against Gonzales had recanted his testimony; after a recent re-evaluation, he’d also concluded that Gonzales “is now a significantly different person, both mentally and emotionally.” The court agreed that Gonzales’s death sentence merited a fresh look.

Once she had come to grips with the dramatic turn of events, Swan spoke with her husband back in Toronto and read scores of social media posts from people pleased with the court’s decision. She also read reactions from “folks who were very angry that the execution was not moving forward.” A petition on Change.org denounced “this monster Ramiro Gonzales,” lashing out at “activist[s] from other countries and states interfering with our Texas legal system.”

Swan tried to talk her way into another visit with Gonzales but was turned down. She returned to Toronto the following evening and went back to corresponding with him by letters and brief phone calls.

Gonzales remains in solitary confinement on death row, waiting for the outcome of the review. The best he can hope for is to spend the rest of his life in the general prison population, with no chance of parole. But another date with the executioner remains a distinct possibility.

Swan once told Gonzales in a letter that “it is not my job to keep you alive. I am here to journey with you no matter what happens.” If anything, the events of last summer reinforced the pastoral side of the relationship. She says her job as a minister is to practise and foster compassion, unconditionally. “I can care immensely about what happened to Bridget Townsend, and be so angry that Ramiro did it, and yet still have an enormous amount of empathy and compassion for Ramiro. I can hold those two things at the same time,” she reflects.

“Compassion is not a finite resource.”

I was reminded of a meeting last spring when Swan and I chatted about her time as a singer-songwriter. Afterwards, I realized I hadn’t asked if she’d ever written a song about Ramiro Gonzales. I messaged her with the question. Her reply: “Half a song. Not sure if I will finish it.” That seems apt.

***

David Wilson is a journalist in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2023 issue with the title ”Keeping faith on death row.“

Good day, I’m deeply concerned about Capital Punishment to be abolished! How can America call itself a diplomatic country when it kills people in the name of the law?? Since about 25 years I’m being activ in writing letters, petitions to the governors, mainly the Texas one!

Kind regards from Germany – Ruth

It’s too bad people like Gonzales couldn’t have found God, remorse and spirituality before they committed heinous unspeakable crimes. It would sure save everyone a lot of trouble and pain. He put himself on death row, No sympathy for the killer. None. All sympathy for his victim. He may be sorry now, but it’s too late for that. The damage is done. Now let justice be done. On June 26th, 2024 Ramiro Gonzales, God willing will meet his maker and the world will be better for it.