Janine Seymour was shocked when she learned that she would not be on the ballot as the Liberal candidate for the Kenora-Rainy River riding in the 2022 Ontario election. She had received local endorsements from two Grand Chiefs, she was a practising lawyer in the region and she had previously run as a candidate for a major party (Seymour ran in 2021 as the federal NDP candidate in Kenora). She found out the news less than one month before the provincial election last June. “I was in a very vulnerable position,” says Seymour, who ended up running as an independent. This time, Seymour would embrace her Anishinaabe spirit name. On the ballot, she was Mi’Azhikwan.

Both times Mi’Azhikwan had pitched her tent with a major party, the results were similar — an opaque internal process that left her feeling isolated and unsupported. Of her experience with the Ontario Liberal Party, Mi’Azhikwan says, “I felt quite used. And then just discarded without explanation, without reason, without warrant in my opinion.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Mi’Azhikwan says she was never told why her candidacy didn’t go further. But if she had to guess, she would point to an interview she participated in as part of the party’s vetting process, describing it as “an interrogation.” One question Mi’Azhikwan recalls being asked is whether she had ever sent an inappropriate picture to a minor. She had not. During the interview with a lawyer and recruiter from the party, Mi’Azhikwan says she did willingly admit to smoking marijuana occasionally, for therapeutic reasons. “I didn’t think about it as a bad thing.”

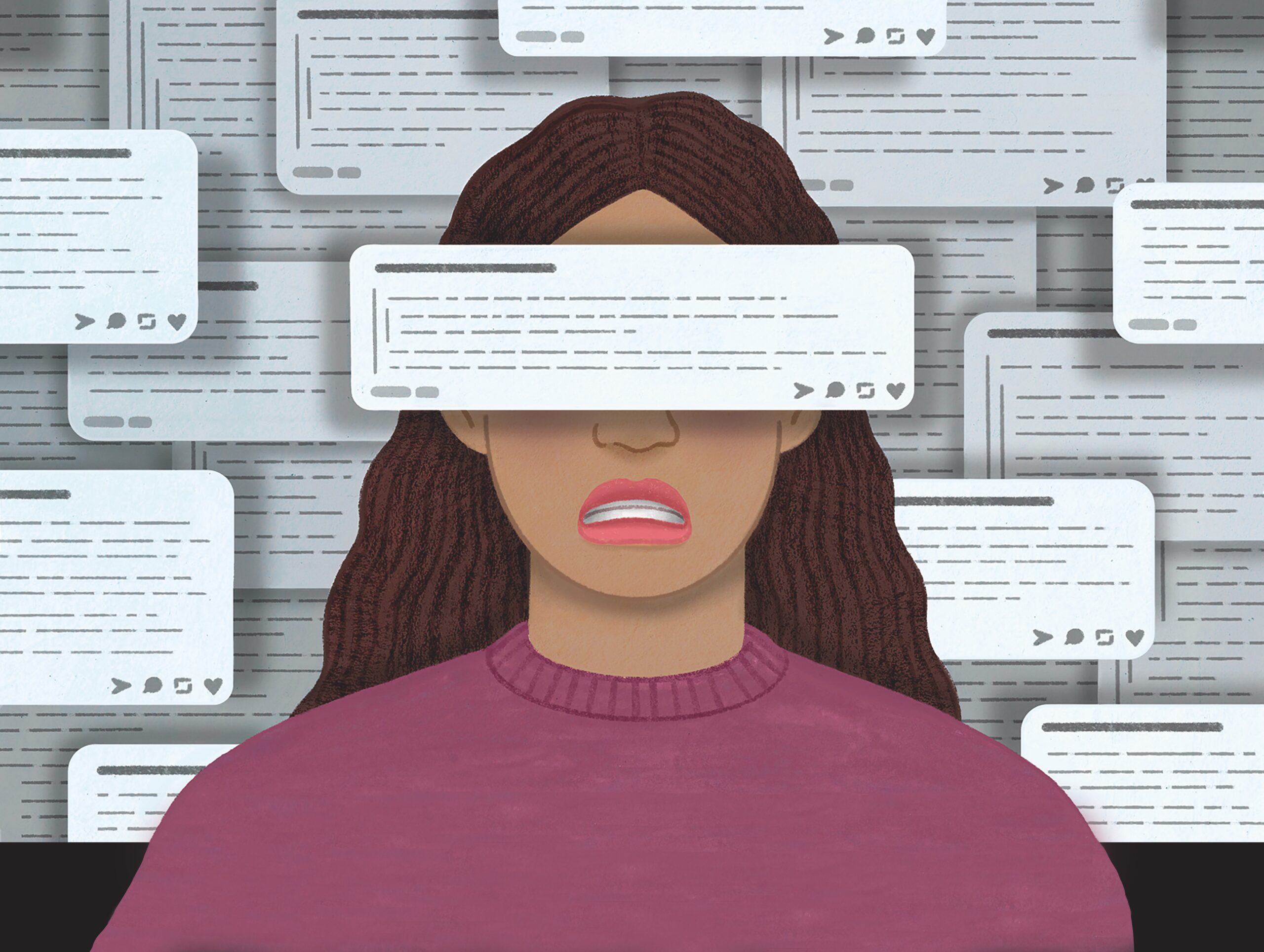

While the Ontario Liberal Party did not select Mi’Azhikwan to run in last year’s election, the party did approve three candidates it eventually dropped: two for problematic social media posts and another who self-published a book that treated homosexuality as a disorder. Recent gaffes like this have led many to question how parties select who will represent them on the ballot, and who the process leaves out. Like Mi’Azhikwan, some candidates and experts point to the vetting stage as invasive, inadequate and unclear. “Who is making the decisions? It’s white men,” says Mi’Azhikwan. “And their policies are completely broken.”

Researchers have described the candidate recruitment and selection process as a “black box” with little public oversight. Parties must report who runs in nomination contests, where riding members choose an official candidate. But earlier stages of recruitment and vetting remain shrouded in secrecy. Erin Tolley, an associate professor in the department of political science at Carleton University in Ottawa, says researchers lack data about which candidates don’t make it through the process and why, but one can gain insight by looking at the demographics of candidates who do. “We can make some guesses based on who actually ends up on the nomination slate,” says Tolley of internal party contests. “And those nomination slates aren’t fully reflective of the demographics of the Canadian population.”

In a study that examined race, gender and intersectionality in legislative recruitment, Tolley looked at more than 800 political aspirants in Canada across three major parties during the 2015 election. She found that as racialized Canadians move through the recruitment process, their presence shrinks at each stage of selection. “Racialized candidates come forward for party nomination in numbers that exceed their share of the population, but parties still show a preference for white candidates,” she wrote in a column. Data collected by Tolley and other researchers reveals that of 4,516 candidates who ran in the 2008, 2011, 2015 and 2019 federal elections, 83 percent identified as white.

According to Tolley, filtering out diverse candidates during the vetting stage can start as early as when a potential candidate simply expresses interest in running under a party’s banner. “Some of that ‘vetting’ is even just a person saying to a member of the party executive, ‘I’m thinking of running to be the Liberal candidate in my riding,’ and the party executive either saying, ‘That’s a great idea’ or ‘Hmm, I’m not sure about that,’” she says. “You can definitely see how it would result in discouragement. That’s an informal way of sifting through the potential candidates, and parties absolutely do that.”

Political vetting is a screening process all major parties employ to ensure they do not “select candidates with controversial pasts or those who are not committed to the party,” notes the Samara Centre for Democracy, a Toronto-based advocacy group for citizen engagement and participation. What is publicly available about the process depicts it as a multi-step regimen. Would-be candidates typically receive a nomination package and complete a detailed questionnaire that asks for very personal information. A committee selected by party leadership then creates a shortlist of candidates by interviewing applicants and conducting background checks. Once an individual is deemed satisfactory, they may participate in a party nomination contest, where members of the riding vote for a candidate. In some cases, a party will simply appoint who will represent it on the ballot.

Other than the basics, the vetting process is opaque. In fact, research by Alex Marland, a political science professor at Memorial University of Newfoundland, and Brooks DeCillia, a journalist and assistant professor at Mount Royal University in Calgary, indicate that applicants are asked to sign “a quasi-legal document declaring that they will not divulge information about the process and may be subject to forfeiting a financial deposit if they do so.”

For all the secrecy surrounding the process, candidates undergoing vetting are expected to be open books. Research by Marland and DeCillia lists an example of a 43-page vetting document from Alberta’s United Conservative Party that questioned applicants about their sexual lives and use of dating apps in response to the 2015 data hacking of the Ashley Madison extramarital dating service. Applicants were asked if naked photos of them existed. Candidates are also routinely required to turn over past and present social media handles so that parties can scrape and scrub the internet for posts that are in the public domain.

For as long as they’ve existed, political parties have scrutinized candidates. “It’s the intensity that has increased,” says Marland. Attitudes changed dramatically in the 1980s after scandals shook prime minister Brian Mulroney’s government, he notes. “There were a lot of people who ended up with criminal charges, and this became a source of embarrassment for the [party].” In the early 1990s, Marland and DeCillia report, fact-checking of candidate resumés grew in response to public outrage over some incidents of embellished and falsified credentials. More recently, vetting has evolved to include even more probing questions. For example, parties are more likely to ask about accusations of sexual harassment, which Marland says is a result of the #MeToo movement. “As society evolves, people get more upset about different things, and political parties react to what is going to be sensitive in the media.”

Experts say the vetting process can help prevent surprises during an election. John Penner, vice-president at StrategyCorp, a business and government-relations consulting company, says that more than looking for gory details to avoid embarrassing a party, thorough vetting ensures that a candidate isn’t dropped during the campaign, costing the party a seat. “If that riding is a competitive riding, or a riding you should win, you don’t want to lose a seat because of it.”

But the process, as it stands now, is “exacting, inadequate and troublesome,” write Marland and DeCillia. Parties can also hide behind the vetting process as an excuse to delay or deter potential candidates. “Within weeks, you should have the vetting process done, even if you’re vetting numerous candidates,” says Allan Bonner, a crisis manager and political consultant. “And stuff is pretty easy to find these days. So any of that delay, hemming and hawing and prevarication, that’s just BS to cover the fact that they didn’t get the job done quickly.”

When Krista Li put her name forward to represent the NDP as the candidate in Calgary-Bow ahead of the upcoming provincial election, she didn’t think it was going to take nearly a year to go through the vetting process. Li, who was at that time president of the constituency association, expressed her interest in running and received a nomination package, which she completed in February 2021. And then she waited, for almost a year, to be vetted. After repeated requests for follow-up, Li says she was given a 45-minute interview in January 2022 with the Alberta NDP’s chief of staff, Jeremy Nolais, and the party’s executive director, Sandra Houston. Li emerged from the meeting feeling deeply confused.

“At no point was I asked what I could bring to the table,” she says. “The entire focus was on what potentially could be embarrassing for Rachel Notley,” the Alberta NDP leader. Li, whose husband is from mainland China, says she was asked if she had any ties to the Communist Party — “an incredibly insensitive question” — or if she had any sexual preferences that might be considered unusual. “Basically, what could someone have on me?” says Li. “I was prepared to come and sell myself as to what I could do as a potential candidate. But instead, I’m sitting there defending myself for 45 minutes. It was an incredibly unnerving experience.”

Bonner says the process isn’t perfect, but effective vetting “treats the candidate as the enemy,” as if you privately “want to destroy that person.” The tactic encourages parties to think like the opposition and unearth any information they might find and use against the candidate, and ultimately the party. “By enemy, I mean, you have to have the zeal to get this person. And if you don’t exercise that zeal, you will pay a price, eventually,” says Bonner. “You’re not helping anybody by going light.”

In a statement to Broadview, the Alberta NDP said it could not discuss individual cases for privacy reasons, but the party did share details about the vetting process generally. “All potential candidates are required to complete the same process, which has two goals. The first is to ensure that every candidate represents the values of the Alberta NDP. The second is to ensure that both the party and the potential candidate are fully aware of any matters that may become public during the campaign and are comfortable with proceeding on that basis,” the statement reads. “The process is invasive because the goal is to be thorough.”

More on Broadview:

- Main drag: Meet the reigning queens and kings of small-town Canada

- Pretendians betray the trust of the Indigenous community — and downplay our struggles

- Peer support workers could be a solution to Canada’s surging mental health needs

While Li turned in information about her social media usage, she says she was told that she was “too expensive to vet” because she had a prolific online presence. Li says her application was never officially rejected by the party — she just didn’t hear anything about it, despite repeated follow-ups.

In response to questions, the party told Broadview that while there are no budget constraints on the vetting process or standard time frames, the work is highly specialized and highly confidential, and so the number of people able to perform it are limited. “Each potential candidate is vetted to the same level of detail, but the volume of public statements, work history, and so forth can vary dramatically from one applicant to the next.”

In February 2022, Li learned that former Calgary city councillor Druh Farrell was seeking the nomination to run for Alberta’s NDP in Calgary-Bow. The announcement blindsided Li, who claims the party made exceptions for Farrell, as the former councillor was not required to notify the constituency association of her intention to seek the nomination, a step that had applied to Li and another aspiring candidate. The Alberta NDP declined to comment on individual cases.

The following month, 15 NDP riding presidents and regional executives wrote a letter to party leaders laying out their concerns about problematic nomination practices, among other issues. These concerns included vetting delays that lead to perceptions of favouritism, and inadequate communication with applicants and local riding volunteers. In response to such criticism, the Alberta NDP committed last year to accelerating the pace of the vetting stage.

Disillusioned by the party’s internal processes, Li stepped down as riding president days after the news about Farrell. Li says in her experience, the candidate selection process reflects the party’s desire to maintain control of who represents them on the ballot. “The vetting process, to me, didn’t seem like it was meant to find good candidates,” says Li. “It was meant to find candidates who could support the brand.”

In their research paper, “Reputation and Brand Management by Political Parties: Party Vetting of Election Candidates in Canada,” Marland and DeCillia write that when parties are viewed as brands, candidates “are expected to use centrally produced messaging; to stick to the party platform when asked about policy; to repeat what the party leader says; and to follow the herd in piling on opponents.” Using vetting to exert control over candidates can have implications for democracy and how we’re governed. “We’re unlikely, in Canadian legislatures, to find representatives who are willing to stand up to the leader,” says Marland.

Sam Kaplun first got involved with the NDP at age 16, inspired by Alexandra Nash’s 2019 race as the federal candidate for the party in Toronto’s Eglinton-Lawrence riding. Only a few years younger than Nash, Kaplun volunteered on the campaign, which Nash lost. After the race, he stayed in touch with the party. In November 2020, he was acclaimed as vice-president of the riding association, and eventually began to consider running as a candidate for the NDP. At first, he planned to run in the federal race, but with uncertainty about the timing, decided to run in the June 2022 provincial election.

Kaplun expressed his interest in June 2021, and about two months later, he was given an interview and provided with the candidate package, which he completed on the same day. He says he then didn’t hear about his application until March 2022, despite following up more than a dozen times. After he reached out for the 14th time, Kaplun says he was told by the party that he had failed the vetting process due to his “social media comportment.” He learned that the party had been displeased by a tweet he had liked that referred to Ontario Premier Doug Ford as a murderer, following the deaths of thousands of seniors in long-term care homes during COVID-19. While Kaplun acknowledged the tweet’s provocative nature, he noted that other NDP politicians have used comparable language. “Jack Layton had similarly, and rather famously, gotten in hot water for criticizing the deaths of homeless people under Paul Martin!” wrote Kaplun in a post-election Twitter thread about his experience with the party. Kaplun added that he had also publicly criticized the Ontario NDP on issues, but wasn’t told whether that played a part in his failing the vetting process. “The party has no obligation to share any information from your vetting report and there is no appeal or complaint process,” he tweeted.

In March 2022, Kaplun and other members of the riding association wrote an open letter to the party opposing its decision to reject him. “To see a highly dedicated and principled young person living with disabilities be refused the opportunity to seek the Ontario NDP nomination due to his ‘social media comportment’ is a great disappointment to all of us and an indication of our party’s unwillingness to stand beside and support equity-seeking candidates through even the smallest instance of controversy,” read the letter. (Kaplun has ADHD and Tourette syndrome.) The letter also identified “structural problems” within the nomination process, including inconsistent vetting standards and not allowing candidates to defend themselves. The Ontario NDP did not respond to Broadview’s requests for comment.

In May 2022, the party selected Natasha Doyle-Merrick, a young Black woman, to run in the riding, and Kaplun stood as an independent. Both were defeated by the Progressive Conservative incumbent.

Velma Morgan, chair of Operation Black Vote Canada, says while vetting differs in some ways across parties, it ultimately comes down to what risks the party is willing to take, and who they want to take those risks for. “I don’t think there’s a set criteria, because if there is, then they don’t apply it across the board.”

Morgan points to recent controversy with Ontario education minister Stephen Lecce, who participated in a mock slave auction during his time as a fraternity leader at Western University. After the news outlet PressProgress reported the story, Ontario Premier Doug Ford defended Lecce, saying, “This is something he did when he was 19 years old in university.” Morgan says the rule applied for Lecce is not guaranteed for every equity-seeking candidate, particularly candidates of colour. “I’m quite sure if it was a racialized person that did something that is thought to be not acceptable now, the party wouldn’t take a risk.”

What does an equitable vetting process look like? And how would it be implemented? Political scientist Erin Tolley says the Canada Elections Act could be modified to require reporting on which prospective candidates came forward to participate in the nomination process, and who didn’t make it. “We’re looking like a stage too late,” says Tolley. “It’s not just who got on the nomination slate and who ran in the nomination contest. What happened before that stage? Because that stage really influences, ultimately, the backgrounds of the candidates who party selectors are choosing from.”

Marland says parties, particularly smaller ones, need increased resources to conduct vetting. And there needs to be more public disclosure about the process itself. “Political parties get [potential candidates] to sign these forms and say it’s all confidential. And often the [candidates-to-be] aren’t told why they were given the boot. So the fact that everything is shrouded in mystery is a bit of a challenge,” says Marland. “The public is not served well when the party controls the information.”

Not being elected to represent her community is still something that saddens Mi’Azhikwan. “The realization that radical change will not come from within [the political system] was shattering,” she says. But she’s still committed to addressing the issues of some of the most vulnerable in her community, including single mothers, children and newcomers. “Leadership takes many different roles,” she says. “I’m going to keep leading, and my community is going to grow.”

***

Ashley Okwuosa is a writer and journalist in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s April/May 2023 issue with the title “No contest.”

Dear Mi’Azhkiwan,

Thank you for your commitment “to addressing the issues of some of the most vulnerable…single mothers, children and newcomers.” I pray you and others like you will find the support you deserve and need to continue.

I’m the daughter of settlers who came here after WWII. At 65, under the tutelage of professor Gregory Scofield, U of Victoria, BC I learned the names of great teachers, writers and film makers: Katherena Vermette, Alanis Obamsawin, Marie Clements. I learned that I was robbed of the true history of this country and this granny is grateful you are willing to share your part of the story. Well done.

Peggy Nash’s recent book, “Women Winning Office” touches on some of the issues raised in this article.

How does the lack of public oversight in the candidate selection process affect the trust Canadians have in their political system? regard Telkom University

How does the lack of public oversight in the candidate selection process affect the trust Canadians have in their political system?