Vikki Hopes was destined to become a journalist. As a child, she loved to write stories. By Grade 7, her teachers were steering her toward a future as a reporter. She got her first taste of journalism writing for the student newspaper in high school. Afterwards, she landed jobs at small papers in British Columbia. In 1991, she joined the Abbotsford News, a community newspaper serving the Fraser Valley area east of Vancouver. She’s been there ever since — 31 years — covering the courts, police and a little bit of everything else.

On the weekend of Nov. 13 last year, Hopes should have been enjoying a couple of days off. Instead, she was laid low by a nasty chest cold. She wondered if it might be COVID-19. As she languished indoors, a river of moisture-laden air from the Pacific Ocean was dumping torrential rain on the Abbotsford area. Illness may have scuttled her weekend off, but it hadn’t blunted her reporter’s curiosity; checking social media on Sunday, Nov. 14, she noticed a video that showed flooding in an area of Abbotsford known as Clayburn Village. At first, she thought nothing of it. A creek there often floods.

That afternoon, Hopes went for a COVID test. Returning home, she noticed an uptick in social media traffic about Clayburn Village. “It looked like a pretty serious situation, worse than they would normally experience,” she recalls. “I thought I’d better get something up online.” She made some calls, fired up her laptop and filed a story that went up on the newspaper’s website, abbynews.com.

Hopes had no way of knowing that the flooding in Clayburn Village foretold a much greater catastrophe. Or that the story she filed would be the first of dozens she’d write over the next three chaotic weeks as epic rains left huge swaths of the Abbotsford area under water. What she did know was that she was one of only two reporters working for the paper at the time. Sick or not, she felt a duty to keep the community informed.

As Hopes told me her story last winter, I found myself reflecting on my own time as a reporter for a community newspaper in Midland, Ont., in the late 1970s. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough. I was new to the game, and my sights were set on bigger things than squabbles on the town council, ambulance-chasing and civic officials who expected reporters to be cheerleaders. I lasted less than two years.

I discovered Hopes and the Abbotsford News as I followed the paper’s coverage of the flooding online last fall. It was exceptional, a lifeline of authoritative reporting for a community in the crosshairs of a major disaster. I also realized something I was too young and headstrong to grasp when I was a small-town reporter: local news reporting can be a calling as honourable and impactful as journalism practised anywhere. Reporters who mostly toil out of the limelight may not realize it, but they are stewards of the local greater good.

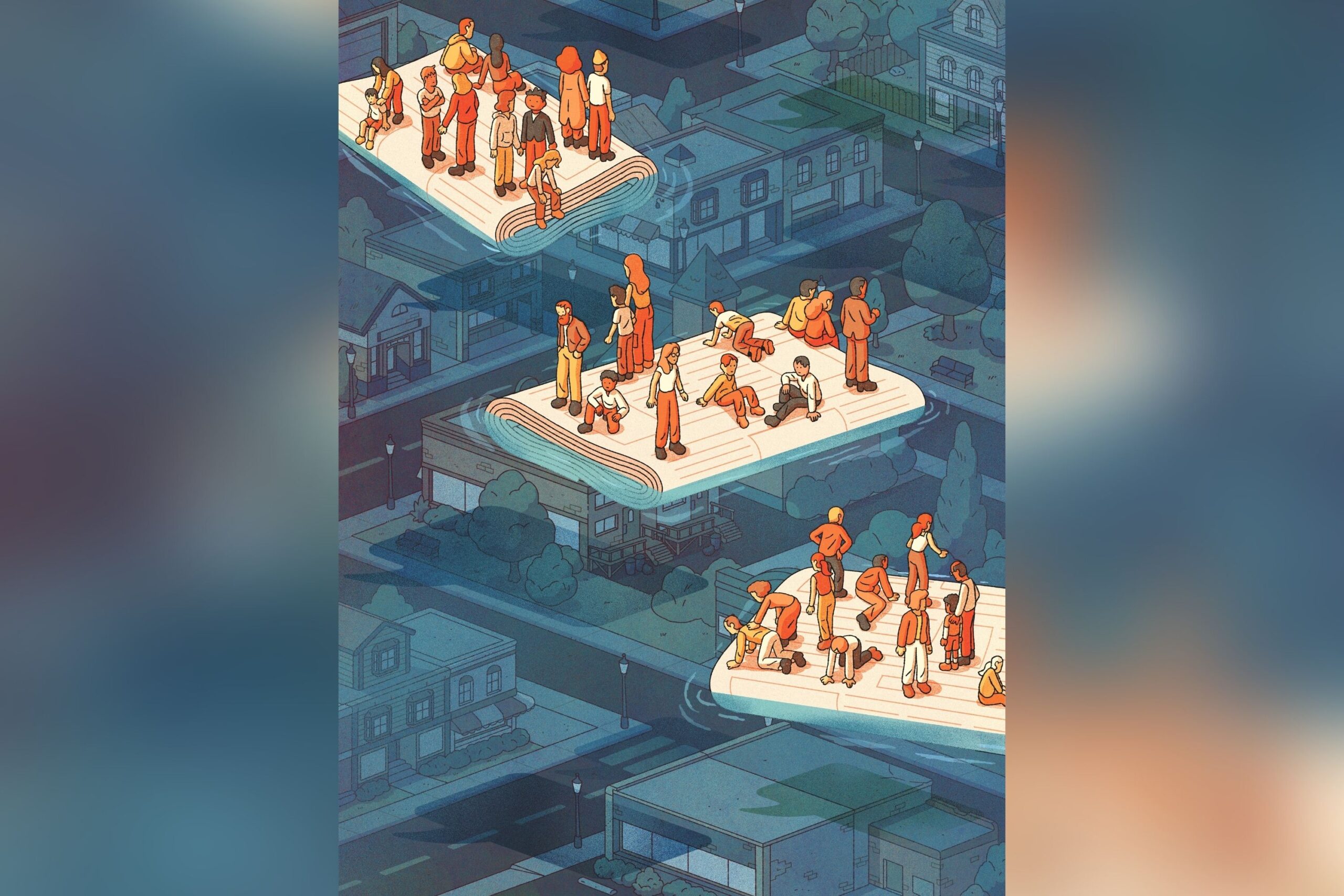

They’re also an endangered species. Whether it’s print, broadcast or digital, news outlets are vanishing at a breathtaking rate. Communities once served by robust local media are being transformed into news deserts starved of credible sources of critical information. Civic engagement and community cohesion suffer, but in this age of big lies, alternative facts and parallel realities, the biggest casualty may be truth itself. The great Abbotsford flood of 2021 was an object lesson in the value of committed, conscientious local journalism. It sprang from a passion for local truth-telling — a passion often taken for granted until it’s gone.

In 2007, April Lindgren left 20 years of high-profile newspaper reporting for a faculty job in the School of Journalism at Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson). A year later, the Great Recession struck. The fallout on Canadian journalism soon became her main research focus.

Lindgren heads the Local News Research Project, an initiative born from her conviction that “local news is as important to a well-functioning community as a good fire service, quality drinking water and safe streets.” Since 2016, she and her collaborators have been charting the changing local media landscape in Canada with a crowd-sourced online map that divides the country into dozens of regional spheres.

The picture is not pretty. The map shows that a total of 450 news operations have closed in 324 communities across the country since 2008. Almost three-quarters of them have been weekly or non-daily newspapers. Start-ups have made only a slight dent in the loss.

COVID-19 has accelerated the downturn. A separate map tracking the pandemic’s impact shows that 53 news outlets closed since March 2020; four-fifths of them were community newspapers. A further 31 local papers cut some or all of their print editions.

The pandemic highlighted a bitter irony: access to public health information has never been more critical, but for many communities it’s never been more scarce.

Numerous factors have triggered the crisis, including advertising revenue that plummeted during the recession and tanked again when the pandemic struck; the migration of readers and advertisers to social media; the consolidation of local news outlets into centralized regional operations; and mergers such as the 2017 deal that saw Postmedia and Torstar Corp. swap 41 community and daily newspapers, 36 of which were eventually closed. Newsrooms that survive takeovers and streamlining often undergo “an absolute gutting,” says Lindgren. “If they aren’t closed, they’ve been scaled back considerably, to the point where…there’s nothing substantial meeting the critical information needs of the community.” She calls this “news poverty.”

The federal government has responded to the crisis with tax incentives and the creation of a $50-million five-year program that subsidizes media organizations for hiring journalists to bolster coverage of civic issues. It’s not a silver bullet but it’s a start. Administered by an arms-length consortium of seven organizations, the Local Journalism Initiative (LJI) currently funds about 130 reporters across the country.

Derek Howard is one of them, working in the same town from which I fled 43 years ago. The paper I worked for, the Midland Times, is long gone, and its competitor, the Midland Free Press, closed in 2013 after a run of 134 years. In their place is an online news site called Midland Today. Howard had been in and out of journalism until a series of freelance articles for the site led to a job offer under the LJI program in 2020.

Howard and I traded tales from the trenches in a long phone chat earlier this year. The stories he files today are virtually interchangeable with ones I filed when I was in Midland — clashes on the town council, controversies over development schemes, concerns around water quality, and the inevitable feel-good pieces about local service clubs, new businesses and worthy civic causes. The only difference is that he loves the work, loves having his finger on the pulse of a community where he has lived most of his life. But he has no illusions about the job being permanent. There’s always the risk that his contract won’t be renewed or that the program will disappear altogether with a change in government. “Right now,” he says, “I’m focused on getting through this first year.”

Vikki Hopes’s COVID test was negative. But she still felt lousy. Across the border in Washington, the Nooksack River was overflowing its banks. Floodwaters charged north, inundating a rich agricultural area called Sumas Prairie between Abbotsford and the neighbouring town of Chilliwack. It had been a lake until it was drained in the 1920s; with pumps overwhelmed, it was a lake again, submerging a section of the Trans-Canada Highway, forcing the evacuation of 1,100 homes and drowning hundreds of dairy cows, thousands of hogs and over half a million chickens.

With the situation becoming more dire by the hour and forecasters predicting further onslaughts of rain, Hopes knuckled down to work, filing stories from home. “I felt we had the biggest story in my career happening right now, and I didn’t want to miss it,” she says.

The paper’s editor couldn’t get to Abbotsford and was quarterbacking coverage remotely, calling in reinforcements from other newspapers in the Black Press Media chain that owns the Abbotsford News. By the third day of the crisis, Hopes was feeling well enough to pop into the newsroom. It was crowded with reporters and crackling with energy — “like a newsroom from the past.” Stories were breaking faster than reporters could write them.

“What happens when a mayor starts talking about an event from five years ago and not even your editor knows what the event was?”

April Lindgren, who leads the Local News Research Project

The paper was lucky to be able to fall back on the resources of a large organization, and the reporters reassigned to help out were fortunate to be working alongside colleagues who knew the local ropes.

In 2018, April Lindgren led a study on working conditions at small-market newspapers, most of them weeklies. The study found that seasoned journalists like Hopes were few and far between. “Many community newsrooms no longer have the veterans who have seen it all and done it all in the community,” wrote one respondent. “What happens when a mayor starts talking about an event from five years ago and not even your editor knows what the event was?”

The value of experience was not lost on civic leaders in Abbotsford who counted on the paper and its website for coverage that reflected the life-and-death gravity of the unfolding disaster last fall. “The reporters at the Abbotsford News understand the diverse needs and opinions of our community like no other,” says Mayor Henry Braun. “When a community faces a crisis, local reporters are able to harness this knowledge and share context other outlets less familiar with the community may not be able to.”

Eventually, the relentless pace of covering the flood began to take a toll on Hopes and others. “You feel like you can’t do another story,” she says. “You don’t know how you’re going to get through this. But you tell yourself this is just temporary, you’re not going through what other people are going through, and the work you’re doing is important.”

The decline of local journalism in Canada mirrors the situation south of the border. Statistics compiled by the school of journalism at the University of North Carolina show that the United States lost one-quarter of its newspapers between 2004 and 2020. More than 2,000 of them were weeklies or non-dailies. At least 200 counties in the United States have no newspaper or other credible news outlet. An analysis by Politico found that areas with low subscription rates to mainstream news sources were significant centres of support for Donald Trump’s spurious campaign in the 2016 presidential election, perhaps tilting the vote his way in a few key swing states. More and more, it seems, lies, half-truths and crackpot theories will move in when fact-based journalism moves out.

“A lot of what we’re seeing in society right now in terms of polarization, in terms of people who are starting to become disillusioned with democracy, with politics and traditional media…is rooted in a loss of journalism at a local level,” says Mike De Souza, a veteran broadcast reporter and now managing editor of The Narwhal, a non-profit online magazine focused on Canada’s environment. “It’s driving people to seek their information from dubious sources, and often that is driven by platforms that are kind of acting as publishers but are not designed to responsibly sort and share information.”

De Souza is chair of Press Forward, a new association of independent, community-focused Canadian media organizations operating mostly online and supported in large measure by readers, not advertising. De Souza says the member publications are joined in common cause to counterbalance the growing mistrust of media and the “tendency for people to buy into misinformation and conspiracy theories.”

No such measures were needed when I worked at the Midland Times. We enjoyed a healthy degree of trust among our readers. Fabricated versions of reality may have lurked in the darker corners of the community, but there was no boombox like the internet for sharing and spreading them. Today, a strong, credible media presence is a critical bulwark against the contagion of dangerous untruths. Just ask people in Peterborough, Ont.

Earlier this year, kawarthaNOW, a 13-year-old online news publication, broke a story about militant anti-vaxxers harassing the new regional medical officer of health, Dr. Thomas Piggott, and his family. Two prominent anti-vaxxers showed up on Piggott’s doorstep one night in January, claiming to be neighbours welcoming him to the community. In fact, they were delivering a homemade “cease and desist” document purporting to show, among other fantasies, that the COVID-19 virus “is a worldwide lie.”

That was the last straw for Jeannine Taylor, kawarthaNOW’s publisher who herself had been harassed for the publication’s coverage of the pandemic and anti-lockdown rallies. Taylor set up a Facebook group supporting Piggott and publicized it on kawarthaNOW. Within days, it had more than 1,400 members. The two anti-vaxxers were arrested and charged with intimidation and harassment of a health official under a federal law that came into force just four days earlier. “It was just a matter of seeing a need and acting on it quickly,” says Taylor, a lifelong Peterborough resident.

Peterborough is hardly a news desert. In addition to kawarthaNOW and another online startup called Peterborough Currents, the city of almost 84,000 boasts a television station, half a dozen radio stations, the venerable Peterborough Examiner and a related tabloid, Kawartha Lakes This Week. The Examiner, a daily, closed its newsroom two years ago; reporters now work from home or out of their cars. After kawarthaNOW broke the story about the anti-vaxxers, other local news outlets picked up on it, prompting a massive outpouring of support for Piggott and public health in general. But imagine this occurring in a media-starved community where it’s open season on the truth. The kind of deceit pedalled by the anti-vaxxers could easily fester into something more toxic. Projected across a wider canvas, incidents like this erode the norms of civility that underpin the social order. Democracy is only as strong as it is healthy at the grassroots. You could argue that it’s diminished each time another news outlet falls silent.

April Lindgren bristled when I complained that there’s too much soft, feel-good reporting in local journalism. I mentioned that a headline reading “Rotary barbecue a success” on a story I wrote was the tipping point for me at the Midland Times.

Stories like this help communities “build a common set of values so that everyone’s not operating in a silo,” she countered. “You shouldn’t dismiss that kind of news out of hand.”

Vikki Hopes has done her share of soft stories for the Abbotsford News; she, too, defends them as community touchstones. And experience has shown that these stories can sometimes evolve into something harder-edged. About a month before the floods, Hopes wrote a piece about a farmer in Sumas Prairie who had begun growing saffron. It was a story “about the great success he was having with this new crop and how optimistic he was about the future.” She thought about him and his ruined crop as the floodwaters rose. Later, she visited his home for a follow-up article. “It was just so sad, to walk on carpet that’s squishing beneath your feet, to smell the mould in the air. He’s crying because he doesn’t know what he’s going to do next. He’s working as a truck driver now.”

More than 50 flood-related stories ran under Hopes’s byline in the Abbotsford News during the peak of the paper’s disaster coverage — all in addition to her regular beats. She and the rest of the reporting team were running on fumes as the crisis dragged on. “I would come home, and the first thing I’d do was throw my bags on the floor, collapse on the couch and look at my husband,” she recalls, her voice trailing off. “But you have to pick yourself up and do it again because this is what we do.”

The Abbotsford News has been publishing in one form or another since early last century. Its coverage of the great flood of 2021 was perhaps its finest hour. In his final daily flood briefing in December, Mayor Braun thanked the local media for their work. “I really don’t think [the Abbotsford News team] know how much I appreciated them during the 27 days we actively dealt with the disaster,” he now says. But all the while, many of the forces challenging community news outlets everywhere loomed in the background. Abbotsford is a one-paper city because Black Press Media purchased a competitor in 2013 and closed it. When Hopes started in 1991, the Abbotsford News published three times a week and carried an editorial staff of a dozen reporters and three photographers. Then it was twice a week. Now, thanks to the pandemic, it’s a weekly, employing three full-time reporters, an editor and a freelance photographer. And it finds itself confronted by a growing clatter of disinformation, distrust and outright hate on social media. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” says Hopes. “The pandemic has just accelerated it.”

Today, flood stories in the Abbotsford News tend to be pieces about the community getting back on its feet. More and more, its pages are repopulated with the everyday stuff of local journalism — police reports, potholes, property taxes, local kids making good, cheque presentations, sports scores and sunny predictions from the chamber of commerce.

I never worked a story on the scale of the Abbotsford flood during my brief stint in community journalism. Chances are Vikki Hopes and her colleagues will never see anything like it again. But the stories they crank out week after week are just as important — each in its own way an episode in the unfolding first draft of a shared community history. The work is rarely glamorous and getting harder all the time. But no one ever said that championing truth and safeguarding democracy was easy.

Reporters labouring in local journalism don’t ask for much more than a steady paycheque and the assurance of a continuing place to publish their stories. Hopes speaks for many when she says, “I’m just happy that we’re still working, that there’s still a newspaper around.”

We should all be happy that she and others like her are still working, and that outlets like the Abbotsford News are still up and running when so many others aren’t. Newsflash: the healthier they are, the better off we all are.

David Wilson is a writer in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2022 issue with the title “Local lifelines.”

I saw it first in 1970 in Newfoundland while working at the family owned newspaper The Evening Telegram. The paper was sold to the Thompson group. The staff was told there would be no changes so not to worry. But all too soon there were. Staff were laid off, new technology brought in and things changed. Today the newspaper is a shadow of its former self having changed owners several times. Broadcast news was never very good, pandering mainly to politicians for easy stories but one of the pluses of broadcasting was that there used to be a real person in the radio station seven days a week. Not so today. As a minister in Cumberland Pastoral Charge in Nova Scotia many years ago there was a snowstorm and we decided to not have Sunday service. We decided to call the radio station to make an announcement. Well it was no longer that easy. The weekend programming was pre recorded and the station was on autopilot. No more personal contact. These days local CBC “news” has a couple of real stories and the rest of the news hour is taken up with human interest and weather. No wonder there’s so much misinformation going around. There’s too much hearsay and not enough solid information. My time in the media as a broadcaster, newsman and photographer was about 12 years and I’ve seen it go steadily down hill.

The comment section appears to use algorithms to filter out personal comments. Doesn’t seem fair but that’s the way this part of the media is these days. When that happens, it is also a form of censorship. If a person is unable to relate personal experience because the algorithm denies that comment, then the publication has lost real contact with the public. Let’s see if the algorithm lets this comment through.

As far apart as we are sometimes in our approach to Christianity. I am always amazed when our thoughts agree in certain matters.

This comment, among others, is when I’m amazed.

(It appears that censorship is not always biased.)

I feel we can agree that we each have an ongoing relationship with God. We just come at it differently.