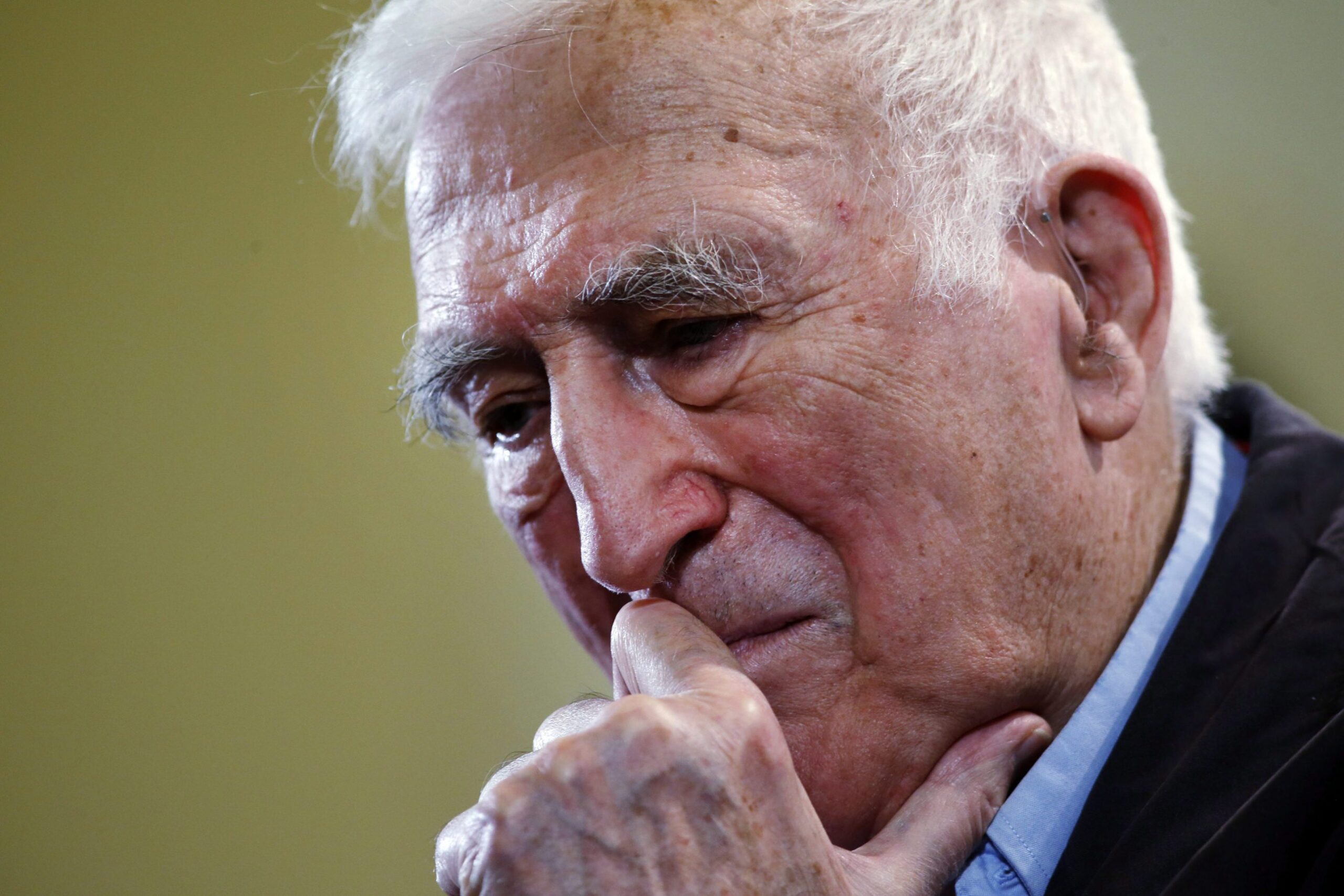

L’Arche International announced on Saturday that an independent inquiry had revealed that its late founder Jean Vanier had “manipulative and emotionally abusive” sexual relationships with at least six women between 1970 and 2005. The organization says the inquiry did not find that Vanier was abusive to people with intellectual disabilities. You can read more from the inquiry here.

In Broadview’s April issue, you can find a review of Carolyn Whitney-Brown’s new book, Tender to the World, about the relationship between L’Arche and The United Church of Canada. The magazine was already printed when we heard about the alleged abuse. Broadview recently spoke with Whitney-Brown, who has researched L’Arche and Vanier extensively, about the news and the lessons it holds for the United Church.

Emma Prestwich: What was your reaction to the news about Jean Vanier?

Carolyn Whitney-Brown: Well, it’s certainly shocking. I felt gutted. You’ll see in my writing, I’ve always been a little uneasy about how much he could be idealized as a saint or put on a pedestal. He didn’t like that himself, but that there was this very, very secret side of him is a whole other thing. I wanted to affirm that he was a normal human being like everyone else, since we all have flaws, but the level of this has been really, really painful to read about.

EP: Besides what L’Arche has put out, are there folks who are involved with L’Arche communities who you’ve spoken to, and what have they said?

CWB: I heard a story that I keep turning over in my mind from France, from Vanier’s own home community, that when the news was announced to everybody in the community, including people with disabilities, one of the women with disabilities immediately said — it would have been in French, of course — “Those poor women, we should write to them and tell them that we are thinking of them.” And then she added something like “that sometimes women say yes, even when they don’t want to.” And I was very moved by that, because her first concern wasn’t for herself or her own hurt, and it wasn’t for Jean Vanier, it was for the women who have been hurt, and she understood that you can say yes and not quite understand whether you did, in fact, say yes.

EP: You’re processing this on a personal level, obviously. What do you think this means for L’Arche as a whole?

CWB: Well, it will take time for L’Arche. I was really moved by their letter. I hope people will read it directly, because they say that while it’s a huge blow and confusing, that they hope what they lose in certainty, they’ll gain in maturity. And I just love that. I think about the United Church too. I think there’s something there that’s a model for us, as we try to face our histories and our realities. So I’m actually quite moved by how L’Arche is responding and it makes me quite hopeful that if they can respond without trying to cover up or soften it, or excuse it, there’s just really incredible leadership there. L’Arche has always been bigger than Jean Vanier.

More on Broadview: South Asian Women’s Centre mends abuse survivors’ lives

EP: It’s interesting you mention a parallel to the United Church and how it grapples with its own history. Which events or parts of its history are a good parallel to this problem?

CWB: Perhaps ironically, as you know, I just published a book about L’Arche and Jean Vanier and the United Church in October. If you think about the residential schools, the United Church is still trying to grasp the enormity of the abuse. That doesn’t mean that nothing but abuse happened, right, there’s a bigger story. But the abuse is huge and very hard to reconcile with the church’s sense of itself in that period. Even now, in terms of what we call truth and reconciliation, I think the United Church is still trying to grasp the truth of what that meant and means. It doesn’t entirely define the United Church now, but you’ve got to grapple with that history.

It reminds me too of the final session of the United Church General Council in 2018, that stunningly fascinating final session where for more than two hours, racialized commissioners stepped up to the microphones, just openly telling their colleagues and friends about their painful experiences. That’s not sexual abuse, but those were stories of disappointment, of betrayal, stories of how power and privilege can carry on without the people who have that power and privilege even noticing its impact. How people can get hurt and even crushed and others not notice. I see a parallel there, of courage, of people being willing to tell their painful stories in the hope that the communities they love can do better. And my sense is the women came forward to L’Arche because they really think this history matters. L’Arche has to grapple with it, and L’Arche can do better. It’ll be OK over time, but they need to know this. I hope the United Church looks at this with a lot of hope and encouragement. The United Church has always been an ally to L’Arche in Canada, and I really hope the church will continue even more so to step up being a friend and an ally in this very, very painful time.

EP: I know this is difficult for you, especially at the time when your book is coming out.

CWB: If I’d known in advance, it might have been an even better book. But the way I end the book, I end by talking about this event at General Council in 2018, of what it meant for the racialized commissioners to step forward with such courage and really try to communicate their experience to their fellow commissioners, and I end with the words of the late, great Ian Macdonald, who was a songwriter and a member of Common Cup Company. One of his songs said, “go be broken, go be whole.” You just get comfortable and then something breaks open and you have to rethink and figure it out over again. I guess I have such respect for the L’Arche leadership taking on being broken open like this with a kind of hope. It’s the great Christian hope, eh? That when you get broken open, that it will lead you to greater wholeness.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

Thank you for this very helpful interview. Yes, L’Arche is bigger than Jean Vanier. In fact it never was about him. It was about all those men and women whose gift of disability taught the world so much. More needs to be written about what this aspect of this movement truly meant and will continue to do so for decades.

YES YES.

The words ” inappropriate sexual relations” describe these few acts by Vanier with another women. We give them the colour of the abusive acts of the film director Weinstein who deliberately used his position of power to force sexual relations.. As a man you almost must not look at a women these days ; if you do here comes the book writers & the lawyers. I DON’T condone sexual abuse but reality is that some men & women use sexual incitement to achieve a personal goal in our society; Vanier was NOT one of those men; you may judge his relationships as inappropriate.