“The man who raised you is no longer here,” the nurse said as we watched my father through the window of the office in the secure unit of the nursing home. Lunch was over, and he had resumed his endless pacing up and down the hallway.

No. Her casual dismissal of our relationship, her callousness regarding the impact of Alzheimer’s on the person and on the family angered me. I remained silent, too irritated to argue. Yet her thoughtlessness planted in me a seed of certainty that would grow into a conviction: his spirit, the essence of who he is, remains.

“Does your father remember you?” people want to know.

The brain contains 100 billion neurons with branches that connect at 100 trillion points. Signals travelling through this forest of neurons form thoughts, feelings and memories. It is these neurons that are destroyed by Alzheimer’s disease. My father is becoming a cave of a brain and a shell of a body, but his heart is strong. He has a whole heart. I don’t know where spirit resides, but I know it’s not only in the brain. It’s in the entire body. We are all spirit.

“Yes,” I always reply.

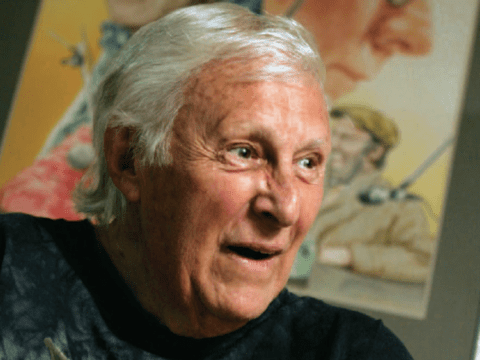

My father, Reg Jewell, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease seven years ago and has lived in a nursing home for more than four years. I feel like I have fought the progression of this disease every step of the way. Then a line in a book leaps off the page: “God dwells within you, as you,” and suddenly I understand where my father is. He is still here.

The man who raised me was impeccable in his hygiene, his hair and his dress. He was particular about keeping his fingernails clean, about wearing a suit to work every day, about his manners. Now incapable of caring for himself, he is dishevelled and slumped and in need of an electric lift and two nurses to move him from the bed to his wheelchair.

Watching his transformation has been extremely difficult, yet as he lingers, I have learned to accept my father the way he is.

Finding that line in the book was a revelation. A blessing. My father is no less a manifestation of the Divine sitting in a soiled diaper and wearing wrinkled cotton pyjama bottoms. He is no less an expression of the Divine when he is unable to speak, unable to swallow without choking, unable to hold his grandchildren. If God dwells in me, healthy and whole, God dwells equally within my father — within the plaques and tangles of the clear-cut neuron forest that is Alzheimer’s.

“My belief is that his spirit is there, that he still exists,” says Rev. David Janzen, the chaplain of the nursing home. “His body and mind are going, but the essence of who he is remains. That’s what we’re touching; that’s what we are reaching — the spirit that is eternal, that is inside, that drives the will to live.” Janzen believes: “Even if there is no sign, Reg is responding deep down.”

There are three basic stages of Alzheimer’s: early, middle and late (with further distinctions within each stage). Carolyn McIntyre is a psychotherapist in New York City who has identified three stages of caregiving: the early stage is a time of surprise, fear, denial, confusion and sadness. In the middle stage, caregivers experience frustration, guilt and resentment. By the late stages of caregiving, there is sadness, guilt, regrets, relief, solace and closure.

I experienced all those emotions throughout my time helping to take care of my father, yet nowhere in the late stage does she list acceptance. Acceptance is the elusive moment when you stop wondering, “How could this have happened to this person I love so much?”; when you stop praying for death (euphemistically referred to as “peace” or “release from suffering”); when you can look at the person you love so much and think, “This is what it is. I have felt sad and resentful and guilty, and I still want you to be released from your suffering, but the only thing left is the love I feel for you.” Without acceptance, there can’t be solace and closure.

The husband of American writer Abigail Thomas was severely brain-injured after being struck by a car. When she realized she couldn’t care for Rich at home, Thomas admitted him to a long-term care facility. Her collection of essays, A Three Dog Life, relates how she learned to cope with the unwanted changes to their marriage and her life. In the essay “Guilt,” Thomas writes about how she looks at Rich and can’t believe this happened to him. Through her mind run all the ways she wishes she could go back and prevent the accident. “But it passes,” she writes. “Rich is necessary to my happiness; I love the person he is now, I love who I am when I am with him, and I can sometimes hold these two truths in my head at once: I wish he were whole, and I love my life.”

Acceptance is a form of hope, a way of understanding that what happened to the person you love isn’t necessarily the tragedy we are conditioned to believe a catastrophic life event to be. The hardest part of acceptance is realizing that this is how life goes. The Sufi poet Rumi wrote what I believe should be the official poem of caregivers. In the opening of The Guest House, Rumi writes, “Every morning a new arrival. / A joy, a depression, a meanness, / some momentary awareness comes / as an unexpected visitor.” He closes the poem with a profound expression of what acceptance is: “Be grateful for whoever comes, / because each has been sent / as a guide from beyond.” When I read those lines, I think of my father, trapped inside a weakened body made useless by a decaying mind, and I hope somehow he has found a way to accept his state as well.

“That’s the mystery of the whole thing,” Janzen says. “You can’t prove it, you can’t demonstrate it. You can just believe it and live out of it and leave the rest of it to God.”

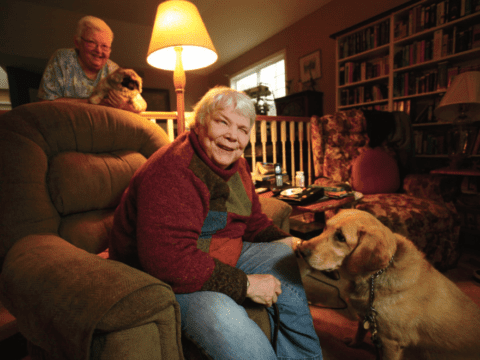

My father is now confined to a wheelchair in a private room. My mother has covered one large bare wall with photographs of their two daughters and four grandchildren; most often, Dad sits facing what we call “the memory wall.” She feeds him twice a day and sits with him for a while after the meal.

One evening, Mum says, “I heard him very clearly say the word ‘no.’ When I looked at him, he was staring at the top of the wall. Not at the ceiling but up there, above the photos. He’d been restless all through supper, moving his arms and legs, but now he was sitting absolutely still. As I watched him, he said, just as clearly, ‘yes.’ Then after a moment, he dropped his gaze and started to fidget again.”

I like to think the exchange went something like this:

Reg, this is God. Are you ready to let go yet?

“No.”

Reg, would you like to stay a little longer?

“Yes.”

The man who raised me is still here.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s February 2009 issue with the title “The memory wall.”