In the summer of 1971, Albert McLeod had an epiphany. He never wanted to be this bored again. While his peers attended high school, he lay on his mother’s couch for months watching old black-and-white movies. Earlier that year, McLeod dropped out of Grade 10 because he could no longer stand the near-daily homophobic bullying and shaming at school. It was not easy being a feminine, gay teenage boy, much less a Métis one (from Cree and Scottish families), in his repressively colonial town of The Pas, Man.

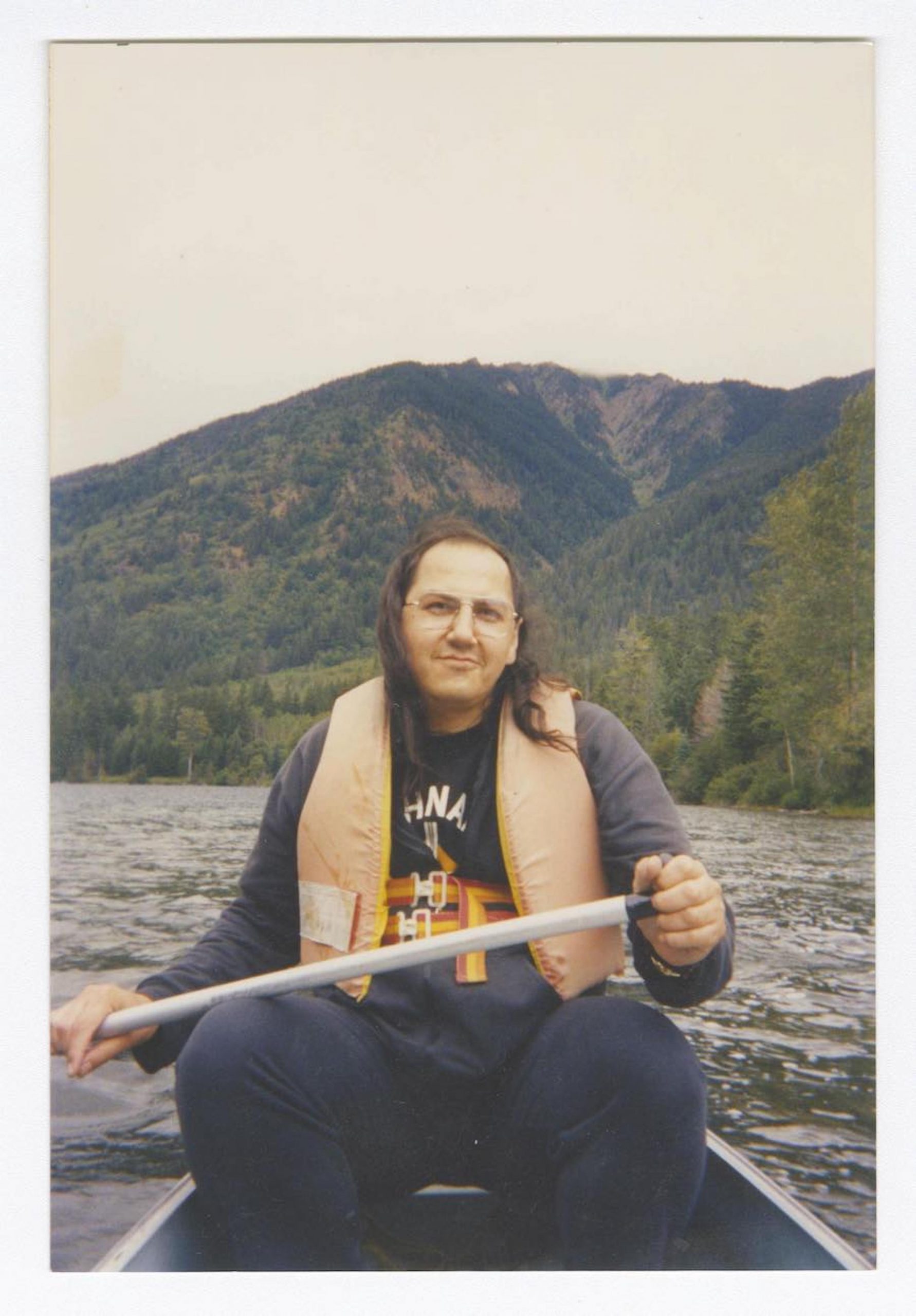

Life had not always been this way. McLeod was born in the village of Cormorant, Man., and spent his early years surrounded by his family and culture. Here he felt accepted. His Cree grandmother, Mary Madeline McIvor, taught him what it meant to maintain his authentic self. Despite colonial pressure, she refused to give up her culture and language, showing her grandson that you can be who you are without shame.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

As he got older, started high school in The Pas and the torment got worse, McLeod knew he had to escape. “So I quit school in Grade 10, and I left the North at the age of 19 as a way to sort of preserve my identity as a queer person, but also my spirituality and integrity,” recounts McLeod.

He didn’t know it at the time, but that act of self-preservation led to a storied lifetime of accomplishments, fighting for the rights and recognition of Indigenous 2SLGBT people around the world. In response to the colonial crisis and the HIV/AIDS epidemic, McLeod and his peers adopted the term “Two Spirit” in the 1990s as a way to create community for themselves and for thousands of other sexually and gender diverse Indigenous people across North America. For him personally, the term also helped bring together his Indigenous, gender, sexual and spiritual identities.

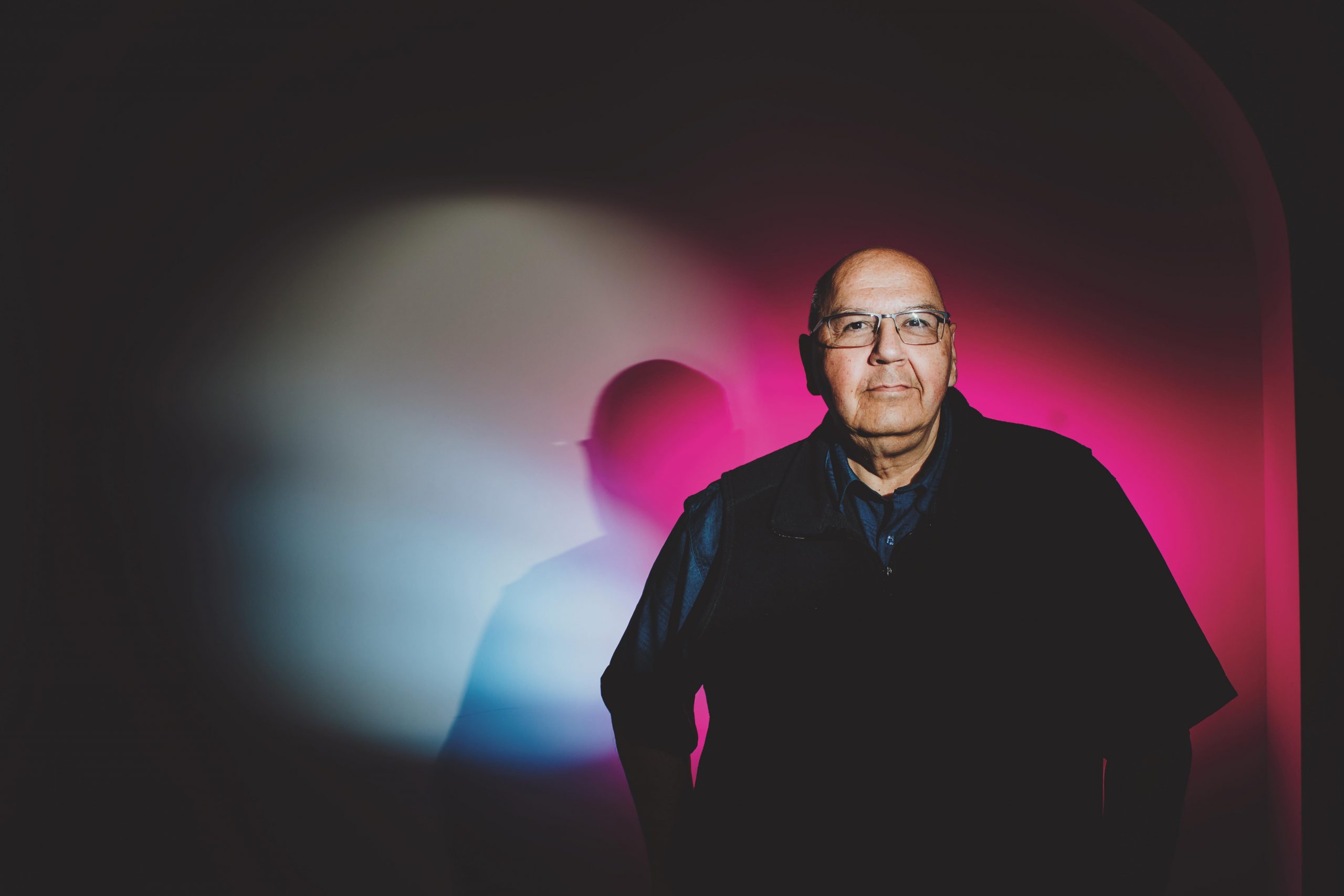

Now 67, McLeod says he doesn’t really care anymore what his pronouns are and sees himself as a “fabulous animate being.” In fact, he says, we all are. He explains that in the Indigenous worldview, humans are first spiritual beings from the universe, and the social dynamics of gender happen later.

As a Two-Spirit Elder, McLeod is not only a living library of Indigenous 2SLGBT history, but he has also been a continuous agent of change. He is lovingly referred to as the Grandmother of Manitoba’s Two-Spirit movement and carries an activist role in the community. He says that he has several Two-Spirit daughters, granddaughters and probably great-granddaughters at this point.

Ancestral grandmothers have always held a special place for McLeod. Born in 1897, his grandmother spoke only the Cree language. McLeod only spoke English. Her knowledge of her culture and her conviction to be herself created a bond not needing words between grandmother and grandchild. She showed him from a young age that in the Cree world view there was always room for feminine boys and masculine girls and non-binary people. He did not have to compromise who he was for others.

Indigenous societies largely did not have a strict gender binary of male or female before European contact. Many Indigenous peoples recognized multiple genders, each having its own unique role in creating a stable and functioning community. When European settlers saw this plurality and fluidity of gender, they viewed it as sinful and backwards. Through residential schools and legislation like the Indian Act, the church and state imposed the gender binary on Indigenous societies.

”I think in many of us [our identity] was something deeply rooted. It was a quest for us; we knew something was missing, that something was not quite right. So we set out to find those truths.”

The gender binary itself, McLeod states, is a tool of colonization. “For Indigenous people, the polarization of the genders has led to this imbalance of authority, of power, in communities,” he explains. “In families, that has led to discrimination where women and children are treated differently. And that leads to violence, particularly domestic violence. So it’s no surprise for me that in Canada we have a national inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people, because it is a legacy of patriarchy, but also the legacy of this imposition of this artificial binary structure.”

For as long as McLeod can remember, his ancestral communities of Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation and Norway House were ringing with the trauma of Indian residential and day schools. Countless generations of culture, language and spirituality were stripped away, and in their place these schools forcibly taught obedience, conformity and shame. As a result, the people in McLeod’s community were afraid to accept or acknowledge children like McLeod who would not — could not — fit the gender binary, and so the homophobic teasing and bullying began.

“It was all about assimilating into western thought, western ways of being,” McLeod says. “But I think in many of us [our identity] was something deeply rooted. It was a quest for us; we knew something was missing, that something was not quite right. So we set out to find those truths.”

***

McLeod was studying art at Brandon University in Manitoba at age 19 when he decided to go somewhere new. He moved to Vancouver in 1979 and found other gay Indigenous men living openly. He also discovered the Greater Vancouver Native Cultural Society, a newly formed organization for LGBT Indigenous people.

It was here that McLeod met like-minded Indigenous people from all over, who had similar stories as his own. Together they reclaimed and strengthened their culture, sexuality and identity, while exploring their social roles as queer folk within Indigenous societies. “There was knowledge there that we all carried,” remembers McLeod. “Our language, our memories of our families, our memories of living on the land — all of that was so critical to our identity in a huge city like Vancouver.”

Many felt estranged from their culture because of their gender and sexual identities. Yet they did not feel like they belonged in the larger LGBT community either, in which they faced racism and ignorance. At the Native Cultural Society, McLeod first saw what a queer Indigenous community could look like. “It was a matter of us coming together and really helping each other validate that,” says McLeod.

Still the Prairies called to him, and four years later, as the HIV/AIDS epidemic took root on the West Coast, McLeod returned to Manitoba, moving to Winnipeg. Here he hoped to connect with an urban queer Indigenous community that was closer to home. Not long after his move back, on a six-hour bus ride returning from visiting family in The Pas, he struck up a conversation with someone who would become one of his closest friends: Connie Merasty. They would go on to work together to promote and protect the rights of the Indigenous LGBT community.

The two already knew of each other as being among a handful of queer Indigenous people in The Pas. Like Merasty and McLeod, many gay Indigenous people had left their communities for cities. Some did it to connect with people like themselves or for adventure; others moved because it was not safe to be out in their home communities. McLeod saw that there wasn’t much support for queer Indigenous people who were in the city for the first time, many combatting racism, exploitation and poverty. The spectre of HIV/AIDS had also begun to find its way to the Canadian Prairies.

In 1986, after a number of Indigenous gay and trans people in Winnipeg died by suicide, McLeod, Merasty and others decided to try to help their community. They formed the Nichiwakan Native Gay Society, one of the first queer Indigenous groups in the country, and provided peer support, social advocacy, counselling and cultural education.

The following year, McLeod, Merasty and a small crowd of activists and allies from all backgrounds gathered outside Manitoba’s legislative building to await the results of the government’s decision to include sexual orientation under the Human Rights Code. If the government voted against their inclusion, they would march in opposition; if it voted in favour, they would walk in celebration. The government voted in favour, and Winnipeg’s first Pride Parade was born.

“I marched in that parade in Winnipeg in 1987 — there were 250 of us. And this year, I think there were 20,000 people,” reflects McLeod. “I do see the changes, and I do see the youth. They’re standing on the sides. They’re happy. And I don’t know if they’re gay or straight or trans, and I don’t need to know. It’s just they’re there. They get it.”

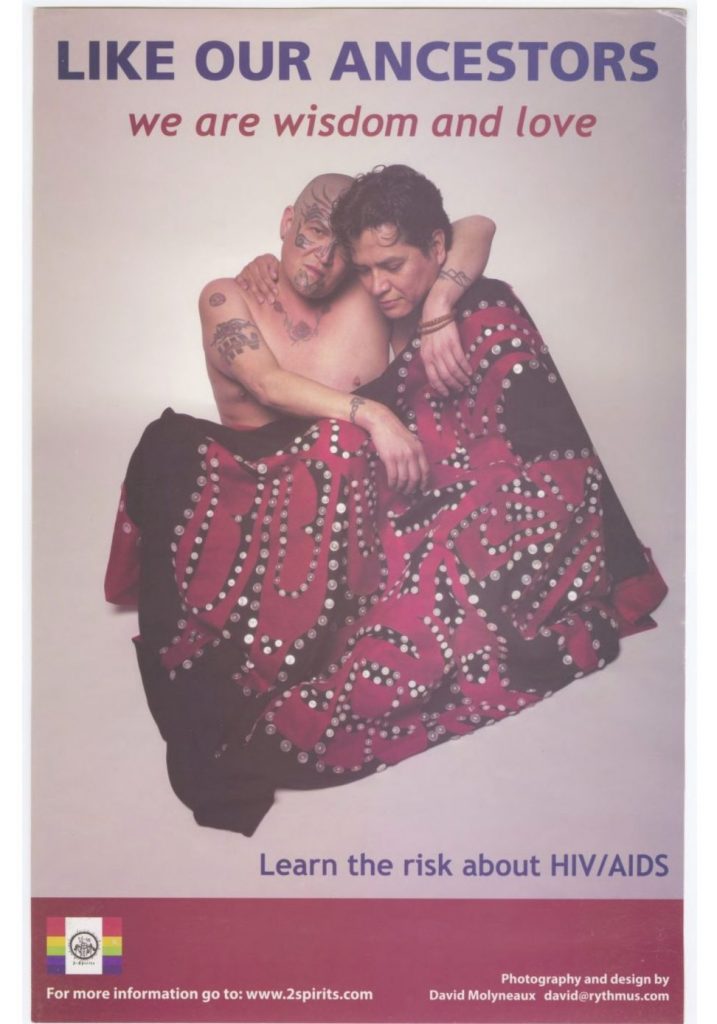

Back in the late 1980s, though, a lot of people didn’t get it. In the face of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, McLeod saw that LGBT Indigenous people were underserved and often overlooked by gay rights advocates and Indigenous health authorities. They were also fighting both racism and homophobia. McLeod knew that they would need recognition as a community with specific needs to get help from healthcare providers. This meant access to life-saving tools, including information in Indigenous languages on safer sex, culturally specific health campaigns, and resources for health and social workers to better understand the intersection of queer and Indigenous culture.

More on Broadview:

- ‘I say with pride that I am from the favela’

- I was ashamed to be Chinese and queer, but now I celebrate

- These Indigenous activists stood up for their rights and were forced to flee Russia

McLeod began to advocate to all different levels of government, navigating colonial bureaucracies and political structures, and securing funding for the community. “He realized that if he didn’t do it, then who was going to do it?” Merasty says. “It really kept him humble because he knew people struggled all the time to navigate those systems.”

Intelligent, passionate, well-spoken and not the least bit shy, McLeod was a natural advocate and very good at creating social connections. Meeting after meeting with government and health agencies, he became one of the go-to proponents for LGBT Indigenous people in Winnipeg. Along with that came invitations from political allies or even the mayor to attend formal events.

Whether it was a community fundraiser or a fancy dinner, McLeod maintained his inclusiveness and sense of humour.

“When I was younger,” Merasty recalls with a smile, “I did a lot of drag performances around the community in Winnipeg. And I was never invited to the big galas — but [Albert] was because he was really active in the community, so he always had an extra ticket. So he would always invite me to dress up in drag and go to these gala events with him, with the mayor of Winnipeg, with the Chiefs, with the politicians. And people would always ask Albert, ‘Who was that tall lady with you?’”

***

While progress was being made for recognition of the Indigenous LGBT community, the fight for survival against the HIV/AIDS crisis began laying the foundation of what would become the Two-Spirit movement. Back then, no one was keeping statistics on how the disease was impacting Indigenous people, but anecdotally activists knew time was running out. They needed to act if they wanted to survive the epidemic.

“We had to decide what to do because our friends were dying of AIDS. We stood up and we went to conferences; we sat on committees; we flew across Canada. Many of us had never been on a plane before and that took courage,” remembers McLeod. “We contributed our voice to the first response…and we’re still doing it today. We haven’t stopped.”

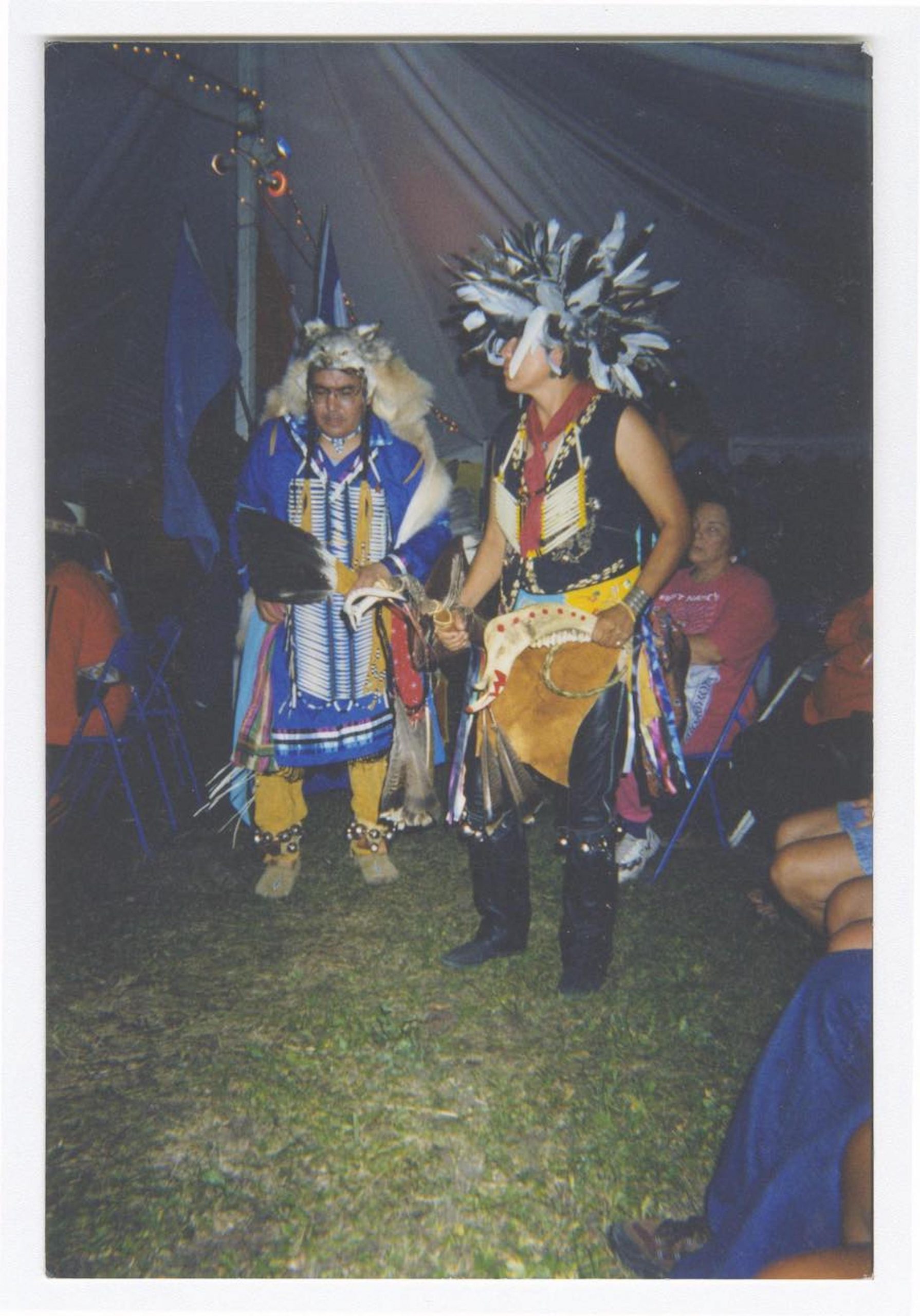

In 1988, McLeod travelled to Minneapolis for the first Annual Gathering of Native American Gays and Lesbians. He had never witnessed so many LGBT Indigenous people together at once. They discussed strategies for the fight against HIV/ AIDS, including the importance of cultural and language-specific resources. It was also a place where attendees could learn about and reconnect with their culture, language, dance and ceremony. Many had been estranged from their communities and spirituality due to adoption, foster care, abuse or residential schools.

One of the first things the gathering decided was that it was to be an annual event held in different locations, on the land and not in the city. It is now one of the longest-running LGBT movements in North America, celebrating 35 gatherings and counting. “We made the effort to meet each other — from the desert in Tucson, [Ariz.], to Long Island, N.Y., to northern Alberta,” explains McLeod. “That is how our ancestors lived. They didn’t live in small territories. They travelled across this continent. They visited each other and traded and told stories and shared their culture and food with each other. So we’ve been doing that for a long time… It is picking up that thread of the past.”

As gay rights activists continued their fight into the 1990s, Indigenous Peoples across the continent were also demanding better for the future. A cultural renaissance was taking place, and Indigenous people stood up for their rights with a revitalized sense of pride, sometimes clashing with Canadian society.

In the early summer of 1990, for example, Oji-Cree politician Elijah Harper refused to accept the Meech Lake Accord, which was designed to gain Quebec’s acceptance of the 1982 Constitution Act. Harper was upset because no efforts had been made in the Constitution to include Indigenous Peoples. The accord was defeated, unable to receive unanimous support.

A few weeks later, in the Kanien’kehá:ka community of Kanesatake, Mohawk Warriors began their defence of the community’s burial ground against a golf course expansion and housing developments. This turned into the 78-day act of resistance commonly known as the Oka Crisis.

While the Kanesatake Resistance grabbed the country’s attention, another historic moment occurred at the Annual Gathering of Native American Gays and Lesbians in Beausejour, just north of Winnipeg. On Aug. 3, 1990, Myra Laramee, now a professor at the University of Winnipeg, had a vision while in ceremony of a new name for their community. She brought the term forward, and “Two Spirit” was received and accepted by those in attendance. Even though people had come from different directions and cultures, they now had a name to unite them.

Some people dismissed the term for being new and trendy, but McLeod believes there is power in the language of reclaiming identity. He says the term is evolving and is opening pathways for Two-Spirit people to rediscover the traditional names and titles they held within their own languages and cultures. “To me, they fit like a puzzle,” McLeod says. “It awakened my spirit and my mind, and gave me a path that, for me, was enlightening, alive, hopeful and full of magic and full of wonder that I could not find in mainstream society or in mainstream Christian religions.”

For McLeod, the term “Two Spirit” is not about two genders but about having two spirits: one connected to the land and his ancestors and the other to the love and inclusivity of family and community. “When I think about Two Spirits, it’s not so much about gender or sexuality. It really is about our place in history and our place in the world,” he says. “As Indigenous people, we have a unique history and a unique path and then a unique future as well.”

***

Over the years, McLeod has collected a lifetime of materials and memorabilia. Posters for fundraisers, photos of friends and allies, VHS tapes of drag shows – and they all document the birth and flourishing of the Two-Spirit movement. In 2011, he began gathering his collection to donate to the University of Winnipeg. It would become the start of the Two-Spirit Archives, which is one of the most comprehensive records of Two-Spirit history in the country.

“The materials that we’ll find in the archives…that is our foundation. Those pieces, those people, those events, those efforts have brought us to where we are today,” says Chantal Fiola, who is Michif from the Red River community in Manitoba and an advisory member of the archives. “Two-Spirit folks in general have had to fight to come back out of the closet and into our communities as a result of colonization. So the archives are really useful in terms of highlighting some of our efforts and also celebrating some of our achievements.”

Fiola is thankful for McLeod and other Two-Spirit Elders who carved the foundation of the community. “That generation has done a lot of really difficult work in creating space within Indigenous communities, within the non-queer and non-Indigenous larger Canadian population,” she says.

After three decades of activism, the biggest win that McLeod can see is that life in Indigenous communities is changing for 2SLGBT people. Many obstacles still bar the path to full acceptance and recognition, but he is blown away by the progress from his high school days. “There are so many Pride events on reserve in Canada and the U.S. this year. It’s phenomenal. I can’t even keep track,” McLeod says with a grin.

“It is really showing that this generation of parents and community leaders are onside. They’re taking responsibility,” he adds. “They’re risking, in some cases, their careers….They are saying we honour and respect our citizens who are LGBTQ and Two Spirit, and we’re going to show it.”

Still, McLeod knows more work needs to be done, and he shows no signs of stopping. It’s too important. He has seen how celebrating Two-Spirit people helps to heal Indigenous societies, making them safer for everyone. “It changes the dynamic, the conversation, the structure of society and community, and provides other pathways for people so they do not have to go through the trauma of trying to attain an identity,” McLeod says. “The pathway has already been made, and now they have choices. And that’s what freedom is about: having choices.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated that the 3rd Annual Gathering of Native American Gays and Lesbians took place in Winnipeg. In fact, it took place in Beausejour, Man. This version has been updated.

***

Ossie Michelin is an Inuk journalist based in Montreal and North West River, N.L.

This story originally appeared in our June 2023 issue with the title “A Fabulous Animate Being.”

You have done your job and broadened my perspective on the whole issue of Indigenous gay rights. I will post this article to my church justice committee. I am glad to meet Albert McLeod. Thanks so much.

This article is very well written.

However, there’s much more complexity in how the movement originated and has progressed than your focus on one person might tell. Albert is an amazing speaker and an engaging presence. From my understanding, there are many others, including one of my closest friends, who started Two Spirit Manitoba and made important contributions in addition to Albert. Women, Indigenous women, are often left out of the many magazine and TV/radio accounts that focus on one person, the face of the movement. There are many sides to the story(s) here.

Nonetheless, when I seek out a person who might speak authoritatively on the topic, I would seek Albert if Albert is available.

Sincerely,

I continue to be enlightened and uplifted with your support of inclusive journalism. Being exposed to new writers who breathe fresh air into our communities and our world by sharing their journeys in all walks through life, continuing to link the past with the present with great belief, foresight and optimistic reality going forward into the future thus providing hopeful opportunity, positive guidance and possibilities and , perhaps, most importantly, courage, strength and supportive community.

Thank you, Broadview, for your ongoing vision in striving to bring inclusivity in all ways to our chaotic, struggling, tired peoples.