Picture it: a cruise ship, once alive with celebration, now rests in eerie silence under an icy coating of barnacles on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean. Salt water has rusted away large sections of the hull, which curiously faces upwards. If you could see inside this overturned ghost ship, you’d notice a giant metal Christmas tree sprawled on the ballroom floor amid other decorations. On the side of the ship is painted the name of the Greek god of tempests: POSEIDON. Fitting, as it was a 27-metre-high tidal wave that capsized the ship on New Year’s Eve half a century ago, killing everyone on board except for a handful of tenacious passengers.

The ship isn’t real. It was the set of a disaster movie, a holiday blockbuster, but there is a lot we can learn from the imaginary wreckage of this fictional ship — about how far we’ve come in terms of leadership and how far we still have to go toward understanding salvation.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Fifty years ago, in 1973, The Poseidon Adventure sailed into the Oscars with eight nominations and won two: Best Song for The Morning After and a Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects (it was up against an unbeatable trifecta: The Godfather, Deliverance and Cabaret). Still, The Poseidon Adventure was a smash hit, earning over US$125 million worldwide. The glittering cast included Leslie Nielsen as the captain, Ernest Borgnine as a mouthy detective and Stella Stevens as his former-prostitute wife, and Shelley Winters and Jack Albertson as a sweet, elderly Jewish couple.

The star of the film was Gene Hackman playing renegade Rev. Frank Scott in tight dress cords and a snug cashmere turtleneck. When the wave hits, he drags his flock out of the rapidly sinking upside-down ship, through a dangerous labyrinth of fire, floods and burning oil, all the way up to the keel and a possible (but not guaranteed) rescue. Though the film’s creators Ronald Neame and Irwin Allen claimed Poseidon wasn’t a Christian allegory, the religious themes were right on course.

Before and after the wreck, Scott uses fiery evangelical-style preaching to motivate other passengers: “Resolve to let God know that you have the guts and the will to do it alone. Resolve to fight for yourselves, and for others, for those you love. And know that part of God within you will be fighting with you all the way.”

His beliefs clash with the cruise ship’s own chaplain, Rev. John (as in the Baptist), who decides to stay and tend to the injured and frightened, confident that salvation will meet them where they are.

Their argument illustrates two sides of the eternal coin for Christians, with some believers sure they have to “fight” for their salvation by being active in their spiritual practice no matter their personal struggles. By pushing through challenges with tough love, and continuing to follow rules, avoid sin, perform sacraments and do good deeds, they’ll be admitted when they make it to the pearly gates. Other believers say all who receive God’s love are welcome without the sweat equity.

It’s when religion and politics swirl together that things get murky. The belief that salvation is granted only to some people —those who work for it—is another way of saying, “God helps those who help themselves.” Politicians who align with that statement often use it to justify laws that push vulnerable people on the margins further out.

I remember Jesus being fairly specific about God wanting us to help others. I suspect Jesus would have substituted Scott’s word “fight” with “love.” Resolve to show LOVE to yourselves, others and those you love. And know that part of God within you will be LOVING you all the way.”

To present-day eyes, the way Scott bullies and screams at his followers is a wild display of 1970s-style leadership. The injured are dragged along for their own good. The frightened are told to pull themselves together and keep moving. There is one path. One leader. He is the most charismatic and assertive man in the pack, so he insists they get behind him or risk being consumed in the fires, literally.

The young women in the film are first ordered to take off their dresses, which Scott deems impractical (although men’s suits and tight pants are fine). Women are called emotional, fat, old and weak. One character, Belle Rosen, played by the incomparable Shelley Winters, begs to lead the team through a treacherous underwater pass because she has experience in endurance swimming. Scott rejects her request and plows forward alone, only to need rescuing by Belle, who dies as a result of the extra time it takes to free him underwater. His bullish insistence on performative heroics is Belle’s demise.

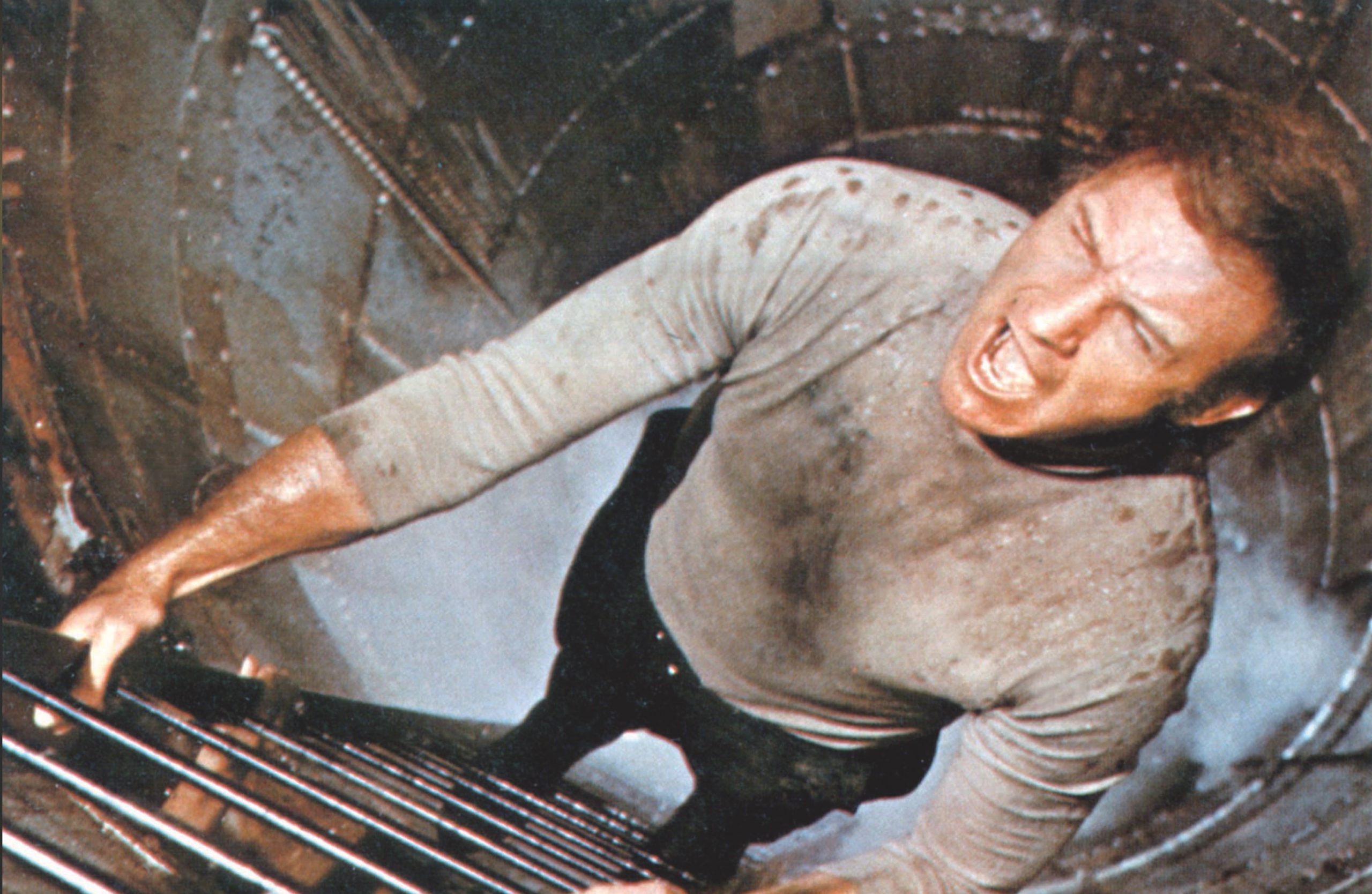

Along the treacherous way, more lives (and two wives, including Belle) are lost to the water before the film ends. Scott, upon finding their path to freedom blocked by a broken steam pipe, hurls himself across a flaming oil spill to hang from the valve wheel, his sweat-drenched muscles rippling, feet at the fire, as he closes the steam valve and screams at God: “What more do you want from us? We’ve come all this way, no thanks to you. We did it on our own, no help from you. We didn’t ask you to fight for us but damn it, don’t fight against us!…You want another life? Then take me!” To complete the allegory, Scott drops into the water in a Christ-like sacrifice, using his death to secure his followers’ entrance to the hull (their salvation) and a happy ending.

More on Broadview:

- ‘We Meant Well’ explores saviourism and complicity in international aid

- In ‘Women Talking,’ the repressed refuse to remain compliant

- ‘Riceboy Sleeps’ explores the burden of belonging

However he gets them there, Scott’s escape plan works, and some of his group are saved. Rev. John, who stayed in the ballroom caring for the injured, is drowned along with all the other passengers. But following Scott’s direction came with a side-helping of verbal abuse, guilt and shame. Was he the only possible leader?

If you had been watching the film closely, you might have noticed another man who was there the whole time: the quiet, humble haberdasher with a gentle smile on his face, James Martin (Red Buttons). All the way through, he shows empathy. When someone is too frightened to move, Martin offers to wait with them until they are ready. When someone is hurt, he carries them. When someone needs answers, he offers a scientific explanation and reassurance for their spirit.

He doesn’t do anything particularly heroic. The only time he screams is when, with tears in his eyes, he calls out to the rescuers for help. And when he sees their faces, Martin’s only question is not for himself or his group, but to ask, “Did you save anyone else?” Martin shows the best of both paths to salvation by pushing himself and the people he cares about forward using love and compassion.

Now, of course, the ship isn’t real; it isn’t at the bottom of the ocean. It’s a disaster movie, not a religious allegory, and Martin is a simple businessman, right? But in the end, I must say, that was mighty Christ-like of him.

***

Allyson McOuat is a writer in Toronto. Her debut book, The Call Was Coming from Inside the House, releases in spring 2024.

This piece first appeared in Broadview‘s June 2023 issue with the title “Shipwrecks and salvation”

There is something almost Christ-like in the pose in which Terry, the young man in the tuxedo who dances with Susan, falls to his death.