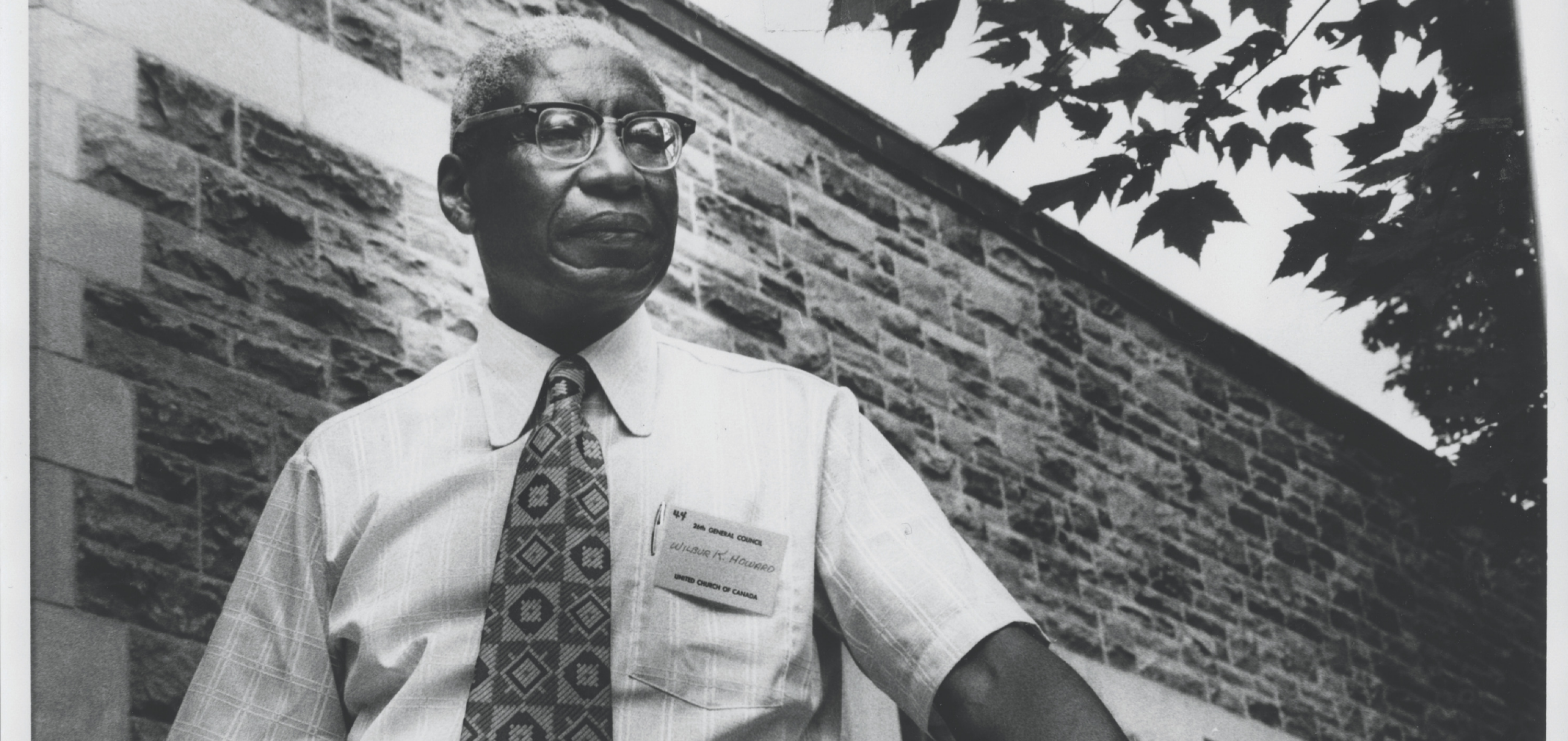

In the spring of 1941, 20 students graduated from Emmanuel College in Toronto. Among them was 29-year-old Wilbur Howard, a man who did not know he would one day occupy The United Church of Canada’s highest elected office. He was a witty and humorous type who wrote in the yearbook that he had been “in demand as [a] poet” and a “post-prandial punster.” He was also the school’s first Black graduate.

It was a peculiar year for Howard to complete seminary school. Most western countries had troops fighting on either side of Nazi Germany. The Canadian Forces had only recently begun accepting Black recruits into the regular army and the officer corps. Some of the powers battling in Europe still held a colonial grip on African states. African-Americans lived under the gaze of Jim Crow segregation laws. Here in Canada, all Japanese Canadians had been declared “enemy aliens” and were asked to register with the government. Canada still had some racially segregated schools.

The world seemed to be falling apart, and The United Church of Canada was dealing with its own troubles. It was in the thick of a minister shortage aggravated by wartime conditions. Church leaders worried about what they saw as a pending crisis: students graduating from theological colleges were called to serve the nation before they could serve the church. “At present, men attending college are not being affected, because they are taking military training,” wrote George B. King, dean of theology at Winnipeg’s United College, to the United Church’s Toronto head office in 1941, “but they will be sooner or later, unless our Church authorities approach the government for clearance on the matter.”

The United Church joined other denominations in lobbying Ottawa to exempt ministry students from compulsory training and service. General Council started to consider summer courses to expedite graduations. A motion was eventually brought forward to study the possibility of preventing ministers from retiring “unless compelled to do so by actual physical incapacity or other sufficient reason.”

Degrees in hand, Howard and his graduating class stepped into this landscape. But few can explain what happened to him over the 24 years that followed. Graduates interested in ministry had to complete a mandatory three-year placement, called a “settlement,” in a congregation. Yet Howard was unable to find a church despite the national shortage of ministers. In fact, he wouldn’t be called to a church until the age of 53.

Howard never publicly mentioned the issue and doesn’t appear to have reflected on it in his diaries now housed in the United Church archives. But many believe this extensive delay was because he was Black. And despite the fact that Howard’s experiences took place over four decades ago, Black ministers in The United Church of Canada still deal with their own forms of racism today. The difference now is that they’re speaking up about it.

Wilbur Kenneth Howard entered the world as an exception — he was born in Toronto on Feb. 29, 1912, a leap-year child. He was a third- or fourth-generation Canadian; his parents, James and Mary, were most likely the descendants of Afro-Canadian or African-American enslaved peoples. In a 1974 article in The Observer, Howard described his mother as a “great church person” who was active in missionary and women’s work in the British Methodist Episcopal Church. “When she died,” he added, “ministers came from all over to share in the service at her funeral.”

His father and brother worked as railway porters — labour jobs were some of the only forms of employment available to Black people at the time. But Howard seems to have taken after his mother. One day when he was young, his white neighbours invited him to a United church, and he never stopped going. At some point, he decided to pursue a life in ministry.

He spent his undergraduate years at the University of Toronto’s Victoria College, where he was heavily involved in campus life. In his yearbook, he wrote that his time at Vic helped him grow “from a freshman, trembling at the obfuscous cosmorama of university life, to a graduate whose feet hit the ground in a new way.” He completed his bachelor of arts in 1938.

Some of the earlier stories of different treatment because of his skin colour come out of Howard’s time at Emmanuel College, where he obtained his bachelor of divinity. During one summer, he did outreach work at Toronto’s Fred Victor Mission. But he spent his two other summers volunteering at camps while his fellow students took up mission posts. According to that same 1974 Observer article, his classmates suggest this was because “the Home Mission secretary was afraid he would be rejected on a charge because of his color.”

Church records betray few details surrounding Howard’s mission placement or the inability to secure a settlement for him upon graduation. Like other graduating ministry students, his name was sent to his home Presbytery, which was responsible for finding him a congregation. But Howard was never placed by Toronto’s Presbytery settlement committee, and there are no records of discussion or action regarding the matter. All that remains are lists of ministers left without a charge, on which Howard’s name repeatedly appears.

The United Church and the country at this time were mostly white in their ways of being. While the denomination does not track race-related statistics, Greer Anne Wenh-In Ng writes in her essay “The United Church of Canada: A Church Fittingly National” that “the ‘face’ of the United Church until and including the postwar baby-boomer church expansion period was still predominantly white and western European, even if it was less exclusively Anglo-Saxon.”

Sure, there were Black ministers in the United Church, but most worked at Montreal’s Union United, which was founded by Afro-Canadian railway porters. Howard, who lived in Toronto, was an outlier.

Despite the fact that he wasn’t able to find a congregation, those were not years he wasted. He served as administrator of the United Church’s Boys’ Work Board, a recreational organization similar to the YMCA, first at the denomination’s national office in Toronto and then in Manitoba. He returned to head office in 1953 to work as the associate editor of Sunday school publications. In this role, he helped shape the controversial New Curriculum of the 1960s. Then, in 1965, he finally got the call — to team ministry at Ottawa’s Dominion-Chalmers United.

John Oldham, whose father knew Howard well, attributes this placement to the influence of Howard’s friend and co-minister at Dominion-Chalmers, Rev. Douglas Lapp. Five years later, Howard went on to lead a church of his own, Emmanuel United, which is also in the nation’s capital. “The congregation wanted him,” recalls Oldham. “People from that church obviously got to know him in Ottawa through the Presbytery meetings and whatnot. They intentionally called him, and they loved him there.”

Howard became president of Montreal-Ottawa Conference and, in 1974, was elected moderator of The United Church of Canada for a three-year term. He continued serving at Emmanuel United even during his time as moderator. He was scheduled to retire in 1977, but the congregation unanimously voted to extend his ministry by a year four times, until he finally stepped down in 1981. Howard died of Parkinson’s disease in 2001 at the age of 89.

Howard’s accomplishments over his years in the church do not erase the systemic nature of the racism that limited his possibilities. Similarly, his decision to remain silent on the racism he faced does not diminish its reality.

Very Rev. Wilbur Howard never married or had children. All that is left to paint his picture are archival documents and articles, along with anecdotes from those who knew him. Many remember him as a man who was both private and modest. Howard rarely imposed his opinion on others. At meetings, he would say “that’s an idea”rather than declare outright whether it was good or bad. He didn’t often share his intimate feelings, let alone his thoughts on race and the church.

He seemed to compensate for his extreme sense of privacy by exhibiting a renowned wit. When elected moderator, for example, Howard quipped, “They had to decide when the commissioners vote ‘Black’ on the ballot whether they meant John Black [a fellow nominee] or me.” Some say this sense of humour is what helped Howard cross racial boundaries.

“He had a respected place in the life of the United Church. And if there were some congregations that didn’t choose to give him a chance, he didn’t dwell on that,” says Very Rev. Bruce McLeod, 89, who served as moderator before Howard and knew him well. “He was a private person. He certainly wasn’t a crybaby. He wouldn’t appreciate his story being used to say, ‘Oh, wasn’t that awful about Wilbur Howard.’ He wouldn’t appreciate that because he didn’t think it was that awful.”

But this isn’t the only opinion that exists on Howard’s silence. “I can see that he had been bruised in terms of racial prejudice and that there was a vulnerability there,” Douglas Lapp told the Globe and Mail after Howard’s death. “Maybe that was why he was so private.”

Howard wasn’t an activist. He was a poet, an author, a minister, a funny and kind man whose spiritual presence was felt and appreciated by those who came to know him. But Howard’s accomplishments over his years in the church do not erase the systemic nature of the racism that limited his possibilities. Similarly, his decision to remain silent on the racism he faced does not diminish its reality.

“Racialized beliefs and practices, although widespread and persistent, are frequently invisible to everyone but those who suffer from them,” write Frances Henry and Carol Tator in the introduction to their book The Colour of Democracy: Racism in Canadian Society. “White Canadians tend to dismiss evidence of their racial prejudice and their differential treatment of minorities. Victims’ testimonies are unheard and their experiences unacknowledged.”

Howard had onlookers who spoke out for him — whether he may have wanted them to or not. A 1974 Globe and Mail editorial about his election as moderator said Howard “has known the face of racism in his ministry,” and his appointment was “just as noteworthy for that fact as would be the first black federal Cabinet minister.” The Toronto Star took a similar view, calling his election as moderator a departure from the “assumptions of white racial superiority” that prevailed not only in Canada but also”among church people.” And in its 1974 report on General Council, The Observer wondered “how many humiliations had been visited on this brother. For he never let it show, never complained and never talked about it.”

But some of the discrimination Howard faced did surface as he took on the role of moderator. In a speech to General Council commissioners after his election, he told a story from early in his career with the church, when during a visit to an Ontario city he was refused service at a restaurant because he was Black. A local United Church leader wrote the national office to say Howard should be let go if he couldn’t be accepted.

“Today,” Howard continued, “is a high moment of acceptance” and “a great step forward.”

It was also a rare instance of openness for a man with a “ministry of eloquent silence,” as Rev. Adam Kilner puts it. Kilner, a minister at Dunlop United in Sarnia, Ont., researched Howard as part of his theology studies. “[He] wouldn’t out of the blue say upon becoming moderator ‘This is a high moment of acceptance’ coming out of a neutral culture. That kind of statement is a statement you make coming out of a rough situation.”

Kilner points out that Howard’s reserved language should be contextualized. The year Howard was giving his speech, a man named Don Andrews, who led a white supremacist organization called the Western Guard, was running for mayor of Toronto (he placed second). The Toronto Star was reporting cases of police brutality against Black men and women and a spike in racial violence across the city.

Over in Nova Scotia, Africville — the historically Black community — had recently been torn down by Halifax officials despite residents’ outcry. In Ottawa, the federal government had refused to sign the 1973 United Nations Convention on the Suppression and Punishment of the Crime of Apartheid. Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated just six years earlier.

Kilner agrees that Howard was soft-spoken. But, given the larger context, he also thinks the moderator could have been being strategic in how he used his voice. Very Rev. Anne Squire, who served as moderator from 1986 to 1988 and passed away in 2017, told the Toronto Star after Howard’s death that “everyone knew he meant acceptance not just as moderator, but as a black moderator.”

The first time Rev. Paul Douglas Walfall of Fort Saskatchewan, Alta., heard about the former moderator’s struggle to be settled, he thought it was odd. “One could argue it takes a while for a minister to get a church. But oh God, so long? And is that not indicative of what the story continues to be for many Black ministers . . . and many Black people in the United Church?”

Douglas Walfall helped bring these racialized experiences to the church’s attention last July when he served as an intercultural observer at the General Council meeting in Oshawa, Ont. On the last day, he took to the podium and delivered a sobering address: “I must confess that for the most part of the past week at General Council, I struggled with the feeling of being invisible. Invisible because in so many ways, I did not see myself, the experiences or cultures of those who like myself live in black or brown skins reflected in the corporate things we did in Council. It was almost as though we do not exist.”

He continued, “I also felt invisible because, to date, I have yet to hear in the Council an acknowledgment that racism exists in our church and that the experiences of racism felt by every Black person within The United Church of Canada are real.”

His speech opened the floodgates as dozens of commissioners came forward with their own experiences of not only racism, but also discrimination and ableism in the United Church. The audience listened as the meeting went overtime for a two-hour session of truth-telling.

“The institutionalized racism that exists in Canada is so deep and saturated and in the system that the level of oppressiveness is intense beyond having it in your face,” one commissioner shared. “It is like having a wall that you cannot see . . . because you don’t know exactly where the issue is.”

Rev. Marlene Britton-Walfall has experienced this wall first-hand. She is currently the minister of Knox United in Thunder Bay, Ont., but she moved to Canada from Barbados in 2013 and first settled in Alberta. During her search for a ministry position, she sat before a church’s three-member hiring committee and took part in an interview that she felt was normal. She was later told she did not get the job because the committee thought the congregation was not ready for a woman. But a few months later, she learned the same congregation had hired a woman — and the new hire was white.

Britton-Walfall was disappointed but not surprised: “I just said, ‘Well, there we go again . . . the whole thing of race becoming an issue.'” She says she felt powerless in this situation and didn’t feel there was anything she could do. “There is no calling out of anybody,” she says. “It’s what it is.”

Besides, speaking out can be exhausting. If a Black minister feels invisible, silenced or erased and raises it within the church, “other people want you to explain yourself, which then makes you so tired that either you regret bringing it up and you just say, ‘You know what? Everything is okay,'” says Rev. Maya Brathwaite of Queensville, Ont. “Or you’ve been browbeaten so much into explaining yourself that you really second-guess yourself the next time something happens.”

The United Church has tried to promote anti-racist values over the years. Training documents are available to ministers and churchgoers alike on the church’s website. These include sermon notes, worship resources and blog posts about racial equity and justice. Ministers must also participate in a mandatory racial justice training program.

These efforts could be a step in the right direction. But Rev. Sadekie Lyttle-Forbes of Windsor, Ont., says, “If you’re a Black minister, it’s a tad more psychologically problematic to offer anti-racism training to your white congregants. If you’re a white minister in the pulpit, you can preach, ‘This is wrong, my people,’ but if you’re Black, it’s harder to say, ‘You people are wrong.'”

It has taken Lyttle-Forbes a while to even identify those “wrong” moments. When she arrived from Jamaica, she didn’t expect to experience racism in Canada — a country with a reputation for being a multicultural Shangri-La. “So when I have an experience of it, I would dismiss it as an isolated event,” she says. “But as it starts to happen more frequently, it begins to occur to me that things are not what I thought they were. And that raises consciousness.”

Sadly, Black ministers have no shortage of examples of racism and microaggressions they can share. Douglas Walfall says he was once approached by a congregant who congratulated him for being a “credit to his race” because he is well-spoken. Kilner was preaching at a funeral where, to his surprise, the son of the deceased announced to the mourners that “my father would have never wanted a Black man leading the funeral.” There are stories of Black ministers whose handshakes are refused or whose white predecessors are regularly invited to events instead of them.

Hearing the stories aired at General Council has been illuminating for the church, even including some Black ministers. “I had no idea that the problem was so pervasive,” says Lyttle-Forbes. “And I think that the wider church also has that sentiment, that they thought this is just a one-off congregational thing — not [an overall] church thing.”

What do the experiences of Brathwaite, Britton-Walfall, Kilner, Lyttle-Forbes, Douglas Walfall and those who have yet to be heard reveal about the present-day church? While many may want to believe that we’ve come a long way since Howard’s time, the current climate surrounding race relations should not hastily be called better. As the United Church begins to deal with its lingering anti-Black racism, it is faced with another question: where does it go from here?

According to Douglas Walfall, “if the church is to have a prophetic voice” in an era when anti-immigrant rhetoric is on the rise in Canada, it first has to “deal with its own stuff.” Only then can it comment on issues of society with integrity. “I think the church is open for a step of reawakening,” he reflects. “The work has started quite a long time ago now. A lot will depend on what happens hereafter.”

This story first appeared in The Observer’s November 2018 edition with the title “Wilbur Howard and the white church.”

Such an interesting, well researched article . Looking forward to reading more work by Mugoli Samba.