I’ve gazed up at the stars from many parts of the Earth in my 24 years — tree planting in northern Ontario, lying on a dock in central Ontario, trekking in the Himalayas, camping in the Sahara Desert. But the stars over the Atacama Desert in Chile are unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Watching the night sky there is as close to an out-of-this-world experience as you can have on Earth.

In search of what is considered the best stargazing in the world, my companion and I boarded a bus in Santiago, Chile’s capital, last March. The daylong ride finally delivered us to the peaceful town of Vicuña, located in the southernmost part of the Atacama Desert. The sun was just setting as we stepped off the bus.

Walking around town at 8 p.m. in search of lodging proved to be more difficult than we had expected. It wasn’t for lack of rooms or friendly locals. It was the sky’s fault. Even in the glow of the town, even before the sun had fully set, the sky was coming alive with stars. I couldn’t help looking straight up as we wandered through town, nearly stumbling right off the sidewalk more than once.

Our necks were still craning upward when we finally found a campground and pitched our tent for the night. It was too late to catch a tour to an observatory, so we simply lay on our backs and took in the spectacle above.

Conditions in the Atacama Desert are perfect for stargazing: the region boasts at least 300 cloudless nights every year, it’s one of the driest places on Earth, and there’s minimal light pollution or radio interference. As a result, observatories have popped up all over, some catering to astronomers and others to tourists.

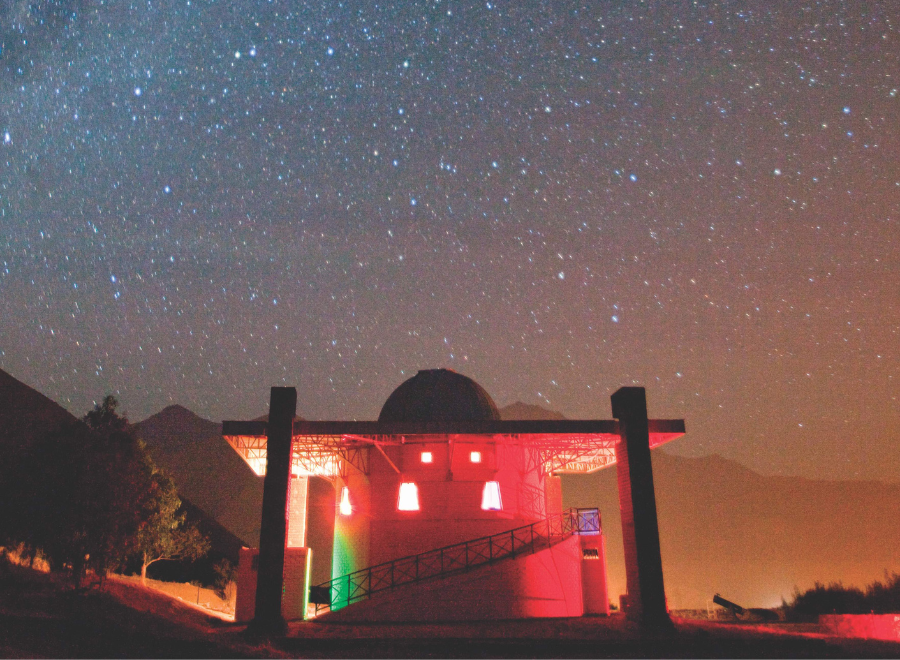

Normally, visitors have to book observatory tours months in advance. We hadn’t, but got lucky: the day after we arrived in Vicuña, we reserved a spot on a tour leaving for the Mamalluca Observatory at 10:30 p.m. that night.

As we drove out of town that evening, the lights of Vicuña faded behind us and the sky grew darker. I kept trying to glimpse the stars from the van, but the bumpy desert roads and the lights of the vehicle made it impossible. Twenty minutes and nine kilometres later, we pulled up to the observatory. I stepped out of the van into the cool night air and looked up.

You have not seen the stars until you have seen them in the Atacama Desert. Everything about the view is massive — more stars than you’d think were possible, stretching across the whole horizon. I’m used to the stars directly above me being the most vivid, with those closer to the horizon being dimmer. Not here: the stars on the horizon shine just as brightly as the stars overhead. The effect is dizzying at first. My usual visual reference points — earth, horizon, sky — all seemed to be swallowed up in the sea of stars above. The sheer magnitude of the vista was overwhelming.

I wasn’t the only one feeling this way. Though dozens of tourists were visiting the observatory that night, hardly anyone spoke, and when we did, we whispered. The hush that fell over us reminded me of a late Christmas Eve service — a quiet reverence in the presence of something greater.

To reduce light pollution, the observatory and surrounding grounds have only a few dim lights for safety. Because of this darkness, I never really saw our guide’s face. But his knowledge of the stars and viewing equipment gave me a window into his personality, and the passion he brought to his job was contagious.

The Mamalluca Observatory houses three types of telescopes. The Meade LX200 is in the main dome of the observatory, as well as Meade Starfinder telescopes and an Orion SkyQuest Dobsonian. The telescope on our tour was the computer-operated Meade LX200. Our guide would enter some co-ordinates, and the telescope would zero in on a specific spot.

Because the magnification of the telescope is so powerful, the computer has to take into account the rotation of the Earth and make constant adjustments. The first object we looked at was Jupiter. I was near the front of our group of about 20 people, and so was one of the first to peer inside the eyepiece. It took a few seconds for my eyes to adjust, but once they did I could see Jupiter, stripes and all.

There was something surreal about it; I had to remind myself that I wasn’t looking at a picture. This was the real thing, floating in the blackness of space, some 629 million kilometres from Earth.

After my turn was over, I snuck back outside. Everyone else was still inside, so for a moment I had the stars all to myself. It was an odd sensation: I felt completely overwhelmed by the universe, but also completely connected to it.

I rejoined the others as they left the observatory and made their way to some lower-powered telescopes outside. Our guide described the constellations to us — they’re completely different from what I am used to seeing in North America. Peering through one of the telescopes, he found Saturn and brought everyone in for a look. Sure enough, it was Saturn, its rings so close I almost felt I could touch them.

The tour was fascinating, but I was starting to lose my bearings. I couldn’t stop looking upward, convinced that I could see Saturn’s rings with my naked eye. A feeling of infinite possibility had taken over, leading me to believe there’s no limit to anything — how far you can see, how far you can reach. It was intoxicating.

And also a bit unnerving. Standing on the edge of infinity can be nauseatingly similar to standing at the edge of a waterfall or cliff. That curious downward tug, that sensation of wanting to jump — and fearing you just might. But here, the tug is in the other direction. With the right push, I felt like I could jump up and soar among the stars.

A voice inside told me that giving in to that tug would mean missing my ride back to Vicuña. I shook off my solitude and rejoined the group, casting one last look at the firmament before climbing back into the van.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s December 2013 issue with the title “Stars of wonder.”