The Church of St. Bartholomew sits on a corner lot in the quiet residential neighbourhood of New Edinburgh in Ottawa. The well-kept grounds of Rideau Hall are across the street, and the governors general who live there have traditionally crossed over for worship. The prime minister lives five blocks down the road.

But despite the Anglican church’s proximity to government and the parish’s connections with monarchy and military, the building itself is modest. It resembles a small English country church in its architecture and blends in with the surrounding houses. It would be easy to stroll by without an inkling of the audacious artistry inside, where an imposing stained glass window casts the sanctuary in bold colours, broodily depicting the arrival in heaven of a slain soldier.

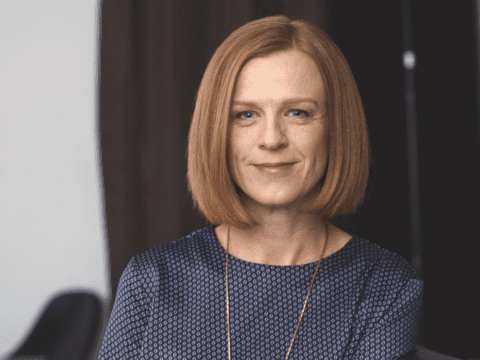

Designed and manufactured in Dublin during the First World War, the Ottawa Window, as it is now known, was unveiled at St. Bartholomew’s in November 1919 to commemorate soldiers killed in the war. In Europe, it had already been praised as a masterpiece. “Nowhere in modern glass is there a more striking example of a courageous adventure in the medium,” one critic wrote. Its creator, the Belfast-born Wilhelmina Geddes, then 32 years old, was beginning to earn her reputation as one of the greatest stained glass artists of the era.

In Ottawa, the reception was reportedly more ambivalent, perhaps because the window was such a departure from the accepted, mostly decorative, aesthetics of the time. “Instead of the usual Late Victorian sentimentality common in Canadian stained glass of the day, this unassuming little church now housed the most expressive tribute to human heroism and sacrifice that Ottawa, and perhaps even Canada, had seen,” wrote Shirley Ann Brown, now professor emerita of art history and humanities at York University, in a 1994 paper.

As Nicola Gordon Bowe, Geddes’s only biographer, has documented, the artist’s contemporaries were also impressed by the forcefulness and passion of her designs, praising their “virile, almost alarming strength,” and the “religion of power and fighting” they conveyed.

In the Ottawa Window, Geddes marshals a company of over 100 figures — soldier saints, mythical martyrs, holy archangels, Arthurian knights and mourning women — into a tableau that memorializes the soldiers as successors in a long line of Christian military heroes. Geddes “has avoided depicting the reality of what [the soldiers] endured,” Bowe writes, “instead representing the morality and physical nobility of those portrayed.”

More on Broadview: Christi Belcourt painting reproduced as mural

It is, one could argue, an awkward artwork for the altar of a church, considering the privileged place in heaven it affords to participants of war. “It’s not the kind of window that a church committee would ever have put in,” admits David Clunie, who currently presides on Sundays in front of the Ottawa Window as the rector at St. Bartholomew’s. “So people were, I think, kind of shocked by it.”

The only depiction of Jesus, Clunie notes, is a relatively miniscule crucifix near the centre of the composition, hovering in a blue glow between the heads of two life-sized Roman soldiers. But for Clunie, this crucifix is an interpretive key that unlocks the meaning of the window. The soldiers, the heroes, the knights — they represent the ways of this world. The crucifix, on the other hand, represents the peaceful power of God that will overcome them.

On Remembrance Day, Clunie preaches this interpretation of the window, urging his congregation not to buy into the myth of heroic violence the window appears to affirm. Instead, he encourages viewers to train themselves upon the Christ figure. And the congregation, Clunie says, has become more proud of the window. They no longer see it as “warmongering propaganda,” he says. “My position is that it’s not that. It’s really got something profound to say, and it’s going to keep saying it.”

It’s not only the congregation who appreciates the window. Students of art history — dozens a year, according to the parish administrator — regularly visit to see this important work first-hand. Beginning in the late-19th century, a revolution occurred in the production of stained glass, spurred on by the anti-commercial and artisanal values of the Arts and Crafts movement. Supporters believed stained glass creators ought to be craftspeople as well as artists, intimately connected to their raw materials, leaders in the manufacturing process and free to pursue their creative instincts. Geddes lived up to this vision, spending much of her adult life designing and assembling windows in workshops in Dublin and London before she died in 1955 at the age of 68. Her Ottawa Window remains a high point of Arts and Crafts glass.

But despite her genius, Geddes’s windows are relatively uncommon. The artist’s output was slowed by mental and physical health struggles as well as financial hardship. Her story, as Bowe notes, is not only one of artistic talent, but also of “a single, city-based woman forging out an independent career in a traditionally male world in early-20th-century war-torn Britain.” This makes her work all the more remarkable — and St. Bartholomew’s all the more fortunate to be the custodian of the only window by Wilhelmina Geddes in North America.

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s November 2019 issue with the title “Precious glass.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

what a terrible theme, what a beautiful work.

Australia lacks such fathomless recognition to the cost of wars.

What an interesting article. I had never heard of this window and want to make it a point to see it on my next visit to Ottawa. What are the hours one can visit on Saturday or Sunday?

Thank you for publishing this.

The small crucifix in the middle lost in the plethora of images that surround it.

So it is today, the image and message of Christ lost or barely noticeable in a chaotic 21st century world needing solutions , cooperation, agreement and actions for its very survival.

The plan and promises of God ,like the hot volcanic magma at the earths core, will someday and unexpectedly, erupt upon the planet and bring both destruction and healing to a bewildered and unbelieving humanity.

All one has to do is read “The Book”.