The map doesn’t seem to lead us where we want to go. My cousin Carina Helland and I know we’re in the right place, more or less, but we can’t figure out where to turn. A rainbow has been following us on our root-finding mission as we drive southeast of the city of Tromsø, in northern Norway. On a hunch, we decide to put away the map and follow the rainbow down a muddy road to the edge of a fjord. Where the arc plunges into the sea, we find a field of fireweed and cranesbills, yarrow and globeflowers. We’ve arrived at our destination: Nerberg.

There’s a flutter in my stomach as I step out of the car and into the meadow on this July afternoon. It was here at Nerberg (my family name) that my father’s father was born in 1902. None of the structures they lived in or used remain, but I know from church records that they fished and kept a flock of sheep here; I know they were Sámi, the only Indigenous people in Europe.

The wind rustles the grasses and wildflowers, setting in motion a sway that rolls from the mountains to the fjord and back again. It’s as if the land and sea are alive; they’re breathing, wishing us bures boahtin, “welcome” in Sámi, on behalf of our kin.

Still, amid the excitement of finding a tangible connection to our roots, I feel a tinge of sorrow. As Carina — the cousin with whom I have the most in common, including identifying as Sámi — and I wade across the meadow to the shore, I wonder: what would my family name have been without colonialism? What would my name have been in Sámi? I may never find out, but that question underpins my search for answers and my motive for coming here, above the Arctic Circle, to Nerberg.

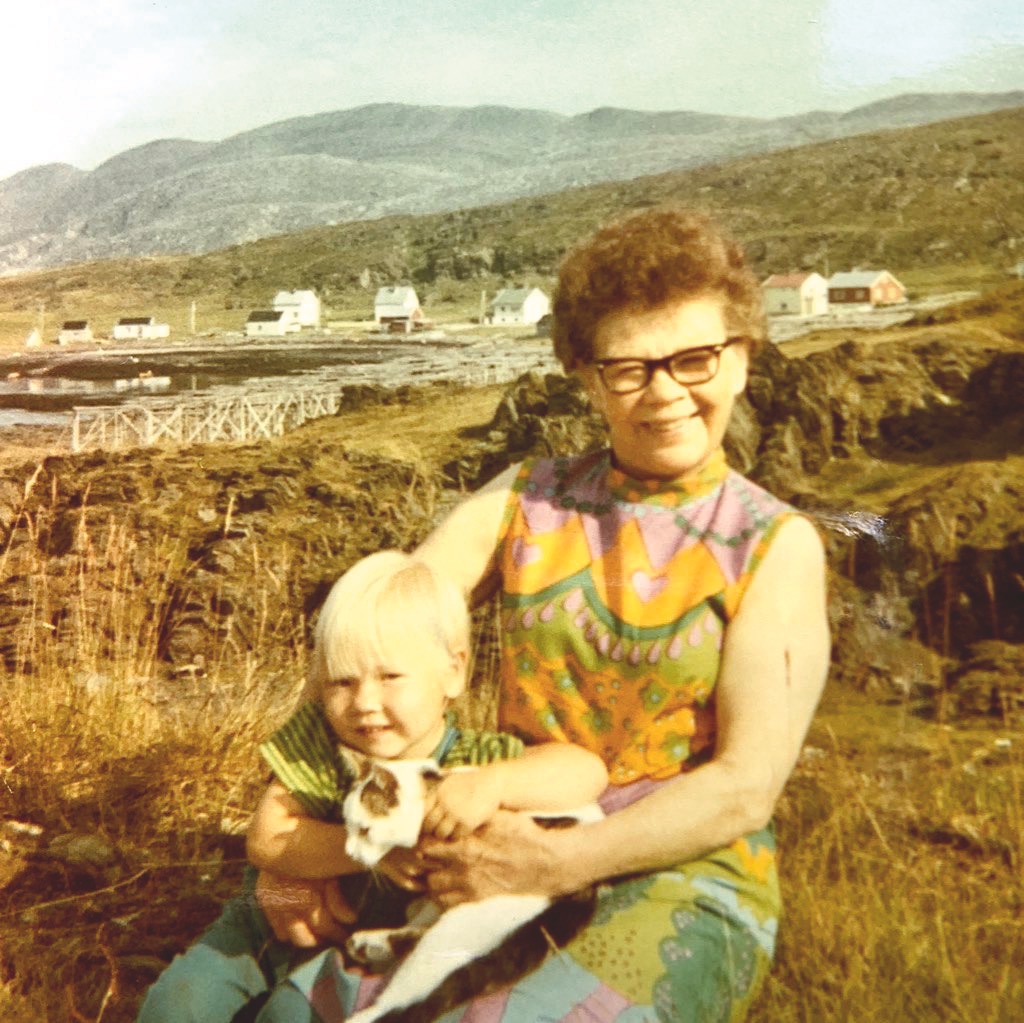

I was about 18 years old when my father told me we are Sámi. We were living in southern Sweden, where I was born, far from the land of our ancestors. I don’t remember the circumstances, but he told me his mother, my grandmother, was Sámi. At the time, he wasn’t sure whether his father — my grandfather — was too. (I confirmed that he was a couple of years ago, when I started actively mapping our past.)

After I moved to Canada from Sweden — even farther away — in my early 20s, I wasn’t looking backward. It took me until midlife, when, in my work as a freelance writer, I had the opportunity to write about Indigenous people who were recovering lost cultures and identities. Amplifying their voices helped me start asking questions about my own Indigeneity and draw parallels between their ancestors’ experiences and those of my foremothers and -fathers. Ojibwe, Inuvialuit, Wendat, Innu — they all encouraged me to shake off the colonial shroud and emerge into an Indigenous light, into my Sámi identity.

In summer 2021, I finally travelled to Norway from my home in Montreal with the purpose of decolonizing my map. Over six weeks, I set course for sections of the coast around Tromsø, including Lyngenfjorden, the fjord where my grandfather was born. I turned stones in Laksefjorden, my grandmother’s birthplace in 1912, and Tanafjorden, where her father was born (both fjords cut long gashes in East Finnmark, Norway’s northernmost county). And for several days, I hung out in and around Mehamn, the fishing village at the top of the European mainland where my grandparents lived for most of their lives and where my father was born.

The common denominator for Sámi in these and other fjords is loss: of language, culture, rights, identity. The more I learned about Sámi realities along my journey, the angrier I got, and the more determined I became to stand up for who I am, who we are. I travelled here to unforget — to give my grandparents, our ancestors, their rightful place in history.

The Sámi and our ancestors have inhabited northern Norway, Sweden, Finland and northwestern Russia since time immemorial, or at least for some 11,000 years. That’s when the last ice started retreating and people followed game, including reindeer, to the coast where the ice disappeared first. While there are several theories of where the Sámi came from — the Volga region, Basque Country — Sámi will often say, “We didn’t come from anywhere; we’ve always been here.”

According to the United Nations, Indigenous people, including the Sámi, “are the descendants…of those who inhabited a country or a geographical region at the time when people of different cultures or ethnic origins arrived. The new arrivals later became dominant through conquest, occupation, settlement or other means.” Sápmi, the traditional territory of the Sámi, stretches from around Lake Femund, four hours north of Oslo, up through Norway and the northern half of Sweden, and across northern Finland and the Kola Peninsula. Sometimes this map even includes southern Norway and southern Finland.

The new settlers — or invaders — of Sápmi were the people from the present-day nation-states to the south: Norwegians and Danes, Swedes, Finns and Russians, pushing their way north to claim farmland, fishing grounds, forests, fur-bearing animals, marine mammals, metals and minerals. The time leading up to the second millennium has been described as a golden era for the Sámi, hunter-gatherers who traded vigorously with the Norse and, in turn, people in continental Europe. Wealthy Europeans had fur coats and seal- and whale-oil lamps thanks to trade with the Sámi more than a thousand years ago.

Things began to change after the year 1000. Kings started encouraging colonization in some parts of Sápmi by enticing settlers with free land and a chance to skip the military (it was difficult to convince people to settle in the Arctic). They squeezed the Sámi for taxes (paid in furs), forcing them to pay to two or even three countries at the same time. Borders, a foreign concept to the Sámi, were drawn and closed, then redrawn and closed again, splitting and uprooting families and preventing reindeer herders from moving their animals between winter and summer pastures on different sides. (The Sámi hunted wild reindeer until the Middle Ages; reindeer husbandry likely became a practice only some 600 or so years ago.) Colonialism and Christianity clamped down with even greater force on all sides of the borders in the 1600s, when power-hungry rulers wanted natural resources to build wealth and fuel wars. And the colonial powers created laws that would pit Sámi people against one another.

On the Norwegian side of Sápmi, where my Sámi roots are, names for people and places were long ago replaced with Norwegian ones. Church books listing my ancestors almost exclusively recorded Norwegian names. For all I know, my great-grandfather Anders Nilsen, who changed the family name to Nerberg, could have been Niilas-Ánde, but the church usually didn’t bother recording Sámi names.

In 1851, the government in Oslo (then called Christiania) formalized Norwegianization, an official assimilation policy that would make the “inferior” Sámi into “civilized,” Norwegian-speaking people. The loss of language and culture was sped up by residential schools, which ran from the mid-19th century to the 1960s, and a 1902 law stipulating that to own land, you had to have a Norwegian name and speak Norwegian.

Learning about these human rights violations made it harder for me to identify with nations that have spent the last 1,000 years subjugating my ancestors. The authorities stripped them of knowledge and language, pride and beliefs, songs and other cultural traditions. They stole their fjords and land; burned goavddis (shamans’ drums) and sometimes noaiddit (shamans) too. They dynamited sieidi, the sacred boulders and natural formations where people left offerings to deities and nature spirits.

Despite 1,000 years of colonialism, my people are still here. But not without wounds and scars from internalizing the shame of being seen as inferior — silent traces that are easier to ignore than the echoes of a traumatic past.

“Sámi heritage was something you never spoke about. It was never a topic of conversation because there was this aggressive Norwegianization,” remembers Sámi artist and activist Hans Ragnar Mathisen. “When I grew up,” says the 77-year-old, “I was quite violently bullied, beaten to the ground. In a way, it’s strange that I survived.”

During my trip, I visit Mathisen in his home studio, close to the sacred Sálašoaivi mountain just outside Tromsø, to find new reference points. Mathisen, who has stood at the forefront of Sámi resistance throughout his life, is also a writer and cartographer — a trailblazer for decolonizing Sápmi. For more than 40 years, he’s been digging up Sámi place names with the help of Elders and scholars and breathing new life into them on his many regional and territorial maps.

He pulls out an example showing Troms County, where he has lived for most of his life (he was raised in Tana, in East Finnmark). He passes it to me. There’s the municipality of Lyngen, represented here as Ivgu in Sámi, and the village of Lyngseidet, or Ivgumuotki, where Nerberg is located. “This map is my biggest contribution to decolonizing and revitalizing Sápmi,” he says, underscoring it was the first one to resurrect Indig-enous place names.

With colourful drawings, vignettes, Sámi symbols and patterns, Mathisen’s maps are as much works of art and cultural documents as they are political statements. Like stories, they help us examine and express our collective self, but they also help us find paths toward self-determination and identity — and to belonging, to oktavuohta.

When you lose touch with the land the way my family has, it can feel necessary to make things up. Because without stories to hold on to — without a sense of oktavuohta — we drift. Maybe that’s why, in my family, there are several versions of where we come from. My grandmother, my áhkku, never wanted to talk about being Sámi. She was sent to residential school, where the most important lesson was to leave behind who you were and where you came from, so it’s no surprise she raised my father and his siblings as Norwegian.

But the provenance and history of my grandfather, my áddjá, has always been a bit of a mystery. According to one of the stories circulating among my cousins, áddjá was an orphan who grew up with a Norwegian foster family that treated him badly. In another, he wasn’t Sámi at all, but a descendant of Genghis Khan, a tale that has been useful to explain why those of us who resemble áddjá have Asian-looking features. Make-believe fosters fake belonging and a sort of reverse pretendianism that led my grandparents and scores of other Sámi to become the folks next door. We’ve all been led off course by colonial maps.

Before my trip, I’d been studying the map of East Finnmark. There, clinging to the very edge of the European continent, is Mehamn, or Donjevuotna in Sámi. Built on fish, which is what drew my grandparents here, the village distinguishes itself for being the northernmost settlement on the European mainland and the northernmost port for the famous Hurtigruten cruise line. Sheltered from the Barents Sea in a bay sprinkled with fishing boats, Mehamn (pop. about 800) is surrounded by a moonscape of sharp-edged boulders. Wildflowers soften the topography in summer; snow smudges it in winter. There’s a sandy beach with Caribbean-blue water, hiking trails through valleys and along cliffs, and a Christmas museum. It’s a place where the locals stop to give you a lift and invite you in for fishcakes and cloudberries.

My father was born in this starkly beautiful place in 1942. He grew up fishing on inland lakes, climbing tall cliffs to pick seagull eggs, sometimes even blowing up abandoned Second World War ordnance for fun. He has told me the story of jumping from ice floe to ice floe during recess, his teacher on his heels, and the time he and a friend thought their rowboat would be flipped by a humpback whale and her calf.

These adventures offered an escape from a postwar home kept in a polar night by poverty and alcoholism and sometimes violence — the legacies or manifestations of trying to numb the double shock of Norwegianization and the German occupation from 1940 to 1945. When the Nazis realized that they were losing the war, they burned just about every school, hospital, fish plant, port, church and home — including my grandparents’ house — leaving a trail of complete destruction from the Russian border all the way to Lyngen, southeast of Tromsø. The strategy was to leave nothing for the Soviet forces that liberated Finnmark. Made homeless, my family and 50,000 other victims were forcibly evacuated to refugee camps in southern Norway. (Another 25,000 fled to the mountains to escape the relocation.)

My father was two years old at the time. He thinks the sorrow of losing their house was too much to bear for my grandparents, who weren’t allowed to return until a couple of years after the war to rebuild their lives. Thinking about colonialism in this context makes me wonder what a war does when it’s stacked on top of the unrelenting messages that you’re degenerate, naive and childlike. It must be like a tank rolling over a pile of broken identities.

As I travel through Sápmi, I meet my dad in Mehamn. He lives in Sweden and Cuba and has come here to spend time with friends and to celebrate his 79th birthday. “Everyone in town was Sámi to some degree, probably to a great degree,” he tells me as we walk to the Nazi gun batteries and bunkers that still blemish a narrow peninsula within sight of where he grew up. “Everyone knew this, but no one ever mentioned it or spoke about it.”

With time, that silence became a concrete bunker for locking away the shame associated with Sámi heritage. After the war, northern Norway was awash in a newfound nationalism, a government-led fervour to modernize and leave behind unproductive communities and backwater ways, including Sámi small-scale farming and fishing. The number of people who still identified as Sámi dropped. My grandparents had shed their Sámi selves long before the war, and their children grew up outside the culture and without the language.

I had hoped to find a spirit of Sámi revitalization in Mehamn, but no. “The shame still hangs over the town; most people don’t want to admit they’re Sámi,” says Torill Olsen. A journalist and author, she has covered Finnmark throughout her professional life. (She’s also my godsister; her father and mine were best friends in childhood.) We meet at the only café in town. It’s packed, people chatting over coffee and cake while awaiting the start of the annual Nordkyn Festival, a celebration of music and culture.

Olsen, who grew up here, moved to Vadsø farther east for high school when she was 16. She’s at the festival to present a project to discourage outmigration from Finnmark and read from her latest collection of essays, Bare Finnmark (Only Finnmark). Her mother was Sámi, from the traditional settlement of Nervei in a sheltered fjord a couple of hours southeast of Mehamn; her father claims not to have any Sámi blood, which, Olsen says, is unlikely given his roots. “The scars of Norwegianization run deeper here in the coastal communities than in many other places,” she explains.

Since Mehamn’s official founding in 1819, people have come for the fishing from all over Norway. Today, there are few families with long-held ties to the area and its Sámi history. Add to that the Nazi obsession with racial “science” and eugenics, formalized by Sweden’s Uppsala University when it opened the State Institute for Racial Biology in 1922. Providing fodder for the Third Reich, the institute carried out head measurements of Sámi and Finns in northern Sweden in the 1920s and ’30s, ostensibly to prove racial inferiority. During the occupation, this idea might have rubbed off on some of the locals, leaving a stain that remained after the war.

“One time, when I was 12 or 13 years old, I was downstairs in our house with one of my brothers,” Olsen tells me. “My father came storming down the stairs with a ruler. He measured our foreheads. When he determined we had low foreheads as opposed to high, Aryan ones, I ran. Or he would have hit me.” She pauses. “I’ve never understood why it was so important not to be Sámi.”

This shame and hatred made Olsen defiant — when the Sámi Parliament was created in 1989, she immediately registered on the voters’ list, strengthening her commitment to her heritage. “What happens if you don’t recognize who you are or where you come from?” she asks. “If a wind blows in and you don’t have roots, you will blow away.”

Nothing grows without roots; nothing changes without a fight. The Sámi Parliament would likely not have existed without both. In 1968, the Norwegian government decided to build a hydroelectric dam on the Alta River, which winds through canyons in West Finnmark before it reaches the ocean. The initial dam placement would have flooded the Sámi village of Máze (Masi in Norwegian) along with important reindeer pastures. After protests from Sámi and environmentalists, the government revised the plan, moving the dam away from Máze. But it would not give in to the river defenders, who staged ever-larger civil disobedience campaigns through the 1970s to demand a full stop to the project. In 1979, and again in 1981, people blocked roads to halt construction work at the site. Both times, Sámi set up camp outside the parliament in Oslo, where some of them started hunger strikes.

This became a turning point in Norway-Sámi relations. News and images of the hunger strikes and hundreds of police dragging demonstrators off the dam site made southern Norwegians — and the rest of the world, including the United Nations — aware of Sámi grievances. Finally, people outside Sápmi saw the deep scars of Norwegianization and losing language, culture and land. In the end, the Sámi Act, enshrined in the Norwegian Constitution in 1987, paved the way for the creation of the Sámi Parliament in 1989 and for the protection and promotion of language, culture and civil rights. (Sámi in Sweden and Finland have their own, independent parliaments; in Russia, there is the Kola Sámi Assembly.)

“I remember that time very well,” my cousin Carina tells me as we drive to Riddu Riđđu, an annual Indigenous music and culture festival in the Manndalen valley — Olmmáivággi in Sámi — not far from Lyngen and Nerberg. Carina is one of the only registered Sámi in our family, giving her the right to vote in elections to the Sámi Parliament.

In Manndalen, people have actively reclaimed language and culture, particularly in the past three decades. Because the valley, tucked farther inland from the sea, is more isolated than Lyngen, fewer Norwegians settled here, preserving a greater degree of language proficiency. But the biggest boost has come from Riddu Riđđu, which means “little storm on the coast” in Sámi.

Since its inception in 1991 as a celebration mainly of coastal Sámi culture, Riddu Riđđu has grown into an international Indigenous festival. In recent years, it has hosted performances by Buffy Sainte-Marie and Sámi superstar Mari Boine. And this summer, the Halluci Nation (formerly A Tribe Called Red) finally played after having had their 2020 and 2021 performances cancelled because of the pandemic.

As Carina steers toward the festival parking lot, tears well up in my eyes. I’ve never been here before, but I feel like I’m coming home. People — my people — are dressed in gákti, whose decorations offer clues as to the wearer’s geographic and family provenance. I see a couple from Kautokeino, in Finnmark, in what must be the most elaborate regalia in all of Sápmi, with stacks of embroidered ribbons sewn onto the sleeves, the shoulders and around the pleated hems.

The gákti from Lyngen is minimalist in comparison, with simple, flat bands around the neck and hem. This décor, I learn, is a remnant of the influence of Laestadianism, a pietistic form of Protestantism practised in some Sámi areas. I’m wearing a royal blue ulloliidni, as is Carina (hers is green). A wool shawl traditionally worn by women, it’s a small gesture, but when people see it, they smile; they know. I feel a sense of belonging, of oktavuohta.

Pride and resilience saturate the festival grounds, from the lunch-time comedy shows and the afternoon film screenings at the Nisga’a Longhouse, to the evening performances by bands, singers and dancers. The festivalgoers not only embrace their Sámi-ness; they flaunt it. It’s very different from my family’s relationship with Sámi identity. When I meet with Lene Antonsen, a University of Tromsø linguist and professor of Sámi, amid the bustle outside the lecture auditorium, she explains the generational shift in attitudes.

As a co-instigator of the local Sámi revitalization and the revival of the Lyngen gákti, which had disappeared from use some 120 years ago, she’s seen the transformation up close. “Young people operate from a different frame of mind because they haven’t experienced the hard assimilation policies from a few decades ago,” she says. “Those in their 20s and 30s don’t carry the same baggage, the shame, as their parents and grandparents.” This leaves them free to be who they are.

Riddu Riđđu’s cool factor with both younger and older generations (there’s also a children’s festival) has helped boost the status of the Sámi language, so much so that the July 2021 edition saw the world premiere of a standup comedy performance entirely in Sámi. I didn’t understand a word, but I loved it. After her show, the comedian Ánne Márjá Guttorm Graven tells me she had to make a conscious decision to use the language regularly in her personal life — and she’s from Karasjok, a core Sámi-speaking area. “It’s so easy — too easy — to fall back on Norwegian,” she says. “But we can’t afford to do that, because we’ve already lost so much.”

Language lets us see where we came from and chart the road ahead. It opens windows to ways of being that have deliberately been obscured for so many of us. To reclaim language is to discover our own truths. I don’t speak Sámi yet (although I am collecting words), and maybe that’s why I feel a need to connect with my ancestors and their land on a physical level, why I needed to stand among the flowers at Nerberg and why I stop several times at the pullout on the road to Mehamn that barely frames the fjord where my grandmother was born.

Their places are my home, too. Because when governments force the removal or assimilation of Indigenous peoples, there’s no one left to claim those maps as theirs and say, “Wait, we are still here.” So I decide to show up on the land.

I pack a tent and set off for Kinnarodden, the northernmost point on the European mainland and a 23-kilometre hike from the village of Mehamn. Ever since my father told me about the long sand beach and clear lakes nearby, I’ve dreamed of this place.

Walking across the rockscape, I think about him rowing from town to spend a day fishing for Arctic char or picking seagull eggs. Sometimes he’d hike, so I’m literally walking in his footsteps. Once, when he and a friend hiked home after a fishing trip with my áddjá, a sea eagle swooped toward them. Luckily, áddjá was carrying a large rack of reindeer antlers; he hoisted it in the air and the bird flew off.

I sit down where the land gets chewed up by the Barents Sea. The sun wraps an arm around my shoulders, like a grandfather who wants to tell a story. My áddjá taught my dad to pluck only one egg from each nest, never take fish that were smaller than a certain size and always leave some berries for animals, to secure food for the future. My dad grew up with Sámi ways without even knowing it. Colonialism tried to erase my ancestors. But I hear their voices in the wind. I see them in the clusters of globeflowers and in the cloudberries — constellations that help me navigate. They are all here; they always were.

Some people say this place is the end of the world. I take out my map and compass, setting my bearing. With all this life — seagulls and char, eagles and reindeer — how could it possibly be the end? For me, it’s only the beginning. And I’m going where I came from.

***

Susan Nerberg is a writer in Montreal.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s September 2022 issue with the title “A journey of unforgetting.”

Very well written, and you truly have captured a lot of the spirit of what it is to be Sámi. Hope to see you again at Riddu Riđđu Festival next year.