Last November at 4 a.m., Christine Nayler and her husband, Tom, were awakened by a foreboding knock on the door. A police officer broke the news: their beloved son Ryan — known for his radical kindness and fierce intelligence — had been found dead not far from their home in Barrie, Ont. The suspected cause was toxic drug poisoning. Later that week, instead of celebrating Ryan’s 35th birthday, his family gathered for his funeral.

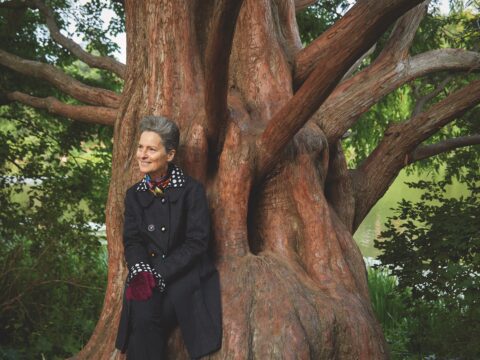

Christine had already been spearheading conversations about mental health and addictions as chair of the outreach committee at Burton Avenue United. After Ryan’s death, she redoubled her efforts. Together with other United churches in the area, her vibrant, justice-seeking congregation fought for the creation of a safe consumption site in its community, a place for people to use drugs with the protection of trained staff. The site promises to stem the tide of deaths in a city hard hit by the opioid crisis.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Across the United Church, other congregations have also been deeply affected by toxic drug supply. In many cases, people in the pews are reeling from the loss of loved ones, and clergy are presiding over the funerals. Inspired by their faith, they’re contributing to public dialogue about harm reduction and speaking up in support of safe consumption sites.

More on Broadview:

- The heartbreaking and deeply Christian task of presiding over fentanyl funerals

- What went wrong when one Bancroft, Ont. United church opened a shelter

- For some women, Alcoholics Anonymous isn’t the way

In Christine’s case, she’s also inspired by her son’s legacy of advocating for society’s most vulnerable. With his twinkling blue eyes and exceptional empathy, Ryan was a born activist. His first protest letter, against child-care cuts, was written at 10 years old and read aloud at a rally at Queen’s Park. He was a vegan and a passionate animal rights activist. A fervent believer in the importance of freedom of access to information, he became a librarian and accepted a position in Edmonton. “He thought it was going to be the beginning of his dream life,” Christine explains.

Instead, a traumatic breakup triggered Ryan’s battle with mental illness. Signs of bipolar disorder, with psychosis, began to emerge. “He was living by himself, and he didn’t know what was happening to him,” Christine continues. “That’s when he started to self-medicate.” Afraid, the Naylers brought him home to Barrie. But his struggle with suicidal thoughts and with drugs — first alcohol and cannabis, then crack cocaine and crystal meth — would continue to wreak havoc on his life. While toxicology results have not yet been released, police believe he died of a fentanyl overdose.

Ryan’s story puts a human face to the staggering statistics: in the last four years, roughly 20,000 people in Canada have died of apparent opioid toxicity deaths. This number has exploded during the pandemic, with over 1,000 deaths in its first three months alone. “We’re losing so many people. These were real people, not numbers, and they were important. They were valued and loved,” says Christine.

Stigma is a significant contributor to the crisis, says Benjamin Perrin, a law professor at the University of British Columbia and author of Overdose: Heartbreak and Hope in Canada’s Opioid Crisis. “We stigmatize substance users more than people with leprosy,” he asserts. Attitudes of blame and judgment have led to people using drugs alone, he adds, with no one available to provide first aid or emergency support if the drug supply is contaminated.

With the arrival of fentanyl in recent years, the likelihood of contamination is considerable. A potent painkiller, up to 100 times stronger than morphine, it’s potentially lethal even in trace amounts. “People from every walk of life, every socioeconomic strata, are affected,” says Perrin. As a society, our aim needs to be saving lives, not punishing people, he insists. Perrin approaches the issue through both the facts and his faith: “God doesn’t want to leave us in a place of sin and trauma. God wants to heal us,” he reflects. “And to get to that place, we’ve got to stay alive.”

By offering clean supplies and medical monitoring, supervised consumption sites keep drug users alive. More than 100 peer-reviewed studies of such sites reveal no serious drawbacks but rather a plethora of benefits: reduced risk of transmissible diseases; access to treatment and other medical care; significant reductions in public injections and injection-related litter; and the presence of someone to administer naloxone, an antidote to opioids, in the event of an overdose.

God doesn’t want to leave us in a place of sin and trauma. God wants to heal us. And to get to that place, we’ve got to stay alive.”

In 2019, Barrie’s branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association and the Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit applied to the city council for a safe consumption site they would jointly operate. The site would also offer medical care and social services, including addictions treatment, help finding employment and more.

The city’s United Church clergy jumped in to support the proposed initiative, signing a public letter endorsing it. “As ministry personnel in the City of Barrie, we often engage with those who live on the margins,” the letter stated. “Our faith teaches us that we are called to act with justice when we see social issues in our community that need to be engaged.”

“There was not a single clergy member in Barrie that did not sign that letter,” says Jeffrey Dale, a staffperson with Shining Waters Regional Council. Interfaith partners quickly joined in, too. Dale, who has personally struggled with substance abuse, has been a prominent voice in the struggle to get the site approved. He organized a series of regional conversations in fall 2020 to encourage churches to engage on the topic, followed by a national series offered through United in Learning last spring.

Christine participated in both, while also leading Ryan’s Hope, an organization inspired by her son’s memory that supports and advocates for people struggling with addictions, homelessness and mental illness.

More on Broadview:

- When kids are in crisis, how can we help them?

- More older women are drinking too much. A new sobriety movements aims to help.

- Toronto clinic is providing free health care to immigrants and refugees

Still, the fight against the site has been formidable. Although it was recently approved at the municipal level after a second vote in June, substantial local opposition has plagued the process every step of the way. Now, the site needs to get the green light from the province. That will likely be where the greatest challenge lies.

For ministers like Rev. David Pallord of Fifth Avenue Memorial United in Medicine Hat, Alta., backlash against safe consumption sites poses a significant threat. After consulting with his congregation, Pallord wrote the city as a way of publicly supporting a proposed safe consumption site there in 2017. “I felt that the church, because of the folks we deal with on a daily basis, and because harm reduction saves lives, needed to step into the breach,” he says. “We’ve been at the funerals. We’ve known some of the parents. And we’ve also seen the drug use on our property and the environs around our church.”

Pallord’s stance is shared by several ministers who were contacted for this story. Take, for example, the congregation of Sackville (N.B.) United, which recently installed a vending machine to dispense free harm-reduction materials. Or Silverspire United in St. Catharines, Ont., where members participate in a walking patrol group to build relationships with substance users and provide harm reduction.

Consider, too, the support of United churches in London, Ont., for the supervised consumption site that is now fully operational there, and the approach of Toronto Urban Native Ministry (TUNM), which provides spiritual and practical support to people, primarily Indigenous folks, who use substances.

“For a long time in the church, we have used a purity-based abstinence model,” says Rev. Evan Swance-Smith of TUNM, “and the reality is that people are still using. Clearly it does not work for everyone. It doesn’t work for the majority of people. We need to ask ourselves: how can we reduce the harm in this activity and the stigma?”

“We’re losing so many people. These were real people, not numbers, and they were important. They were valued and loved.”

The United Church of Canada doesn’t currently have an official position on harm reduction. In 2018, First United Church Community Ministry Society in Vancouver brought a proposal to General Council to ask the denomination to support the decriminalization of illicit drugs. The proposal was referred to the General Council Executive, which decided not to take any action.

Jeffrey Dale is hoping that changes. “We need to put pressure on the church to recognize the fundamental right to life and health for all people,” he argues. “Harm reduction is the first step…. If we can help someone live another day, then we can help them build a better future.”

In the meantime, ministers and lay people in the United Church will continue to fight for harm reduction and safe consumption sites. “My son was a gift to the world,” says Christine Nayler. “Even when he was struggling, he was still doing everything he could to make the world a better place…. The way that I can honour him is by continuing his legacy.”

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer and editor in Barrie, Ont.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s Oct/Nov 2021 issue with the title “Safe Harbour.”

Since this story was first published, there sre study’s that dafe consumption policies in isolation are not really reducing addictions among the people who rely on these sites. An updated report would be helpful.