This interview is the first in a six-part series about rethinking the police. A new article will be posted every Wednesday.

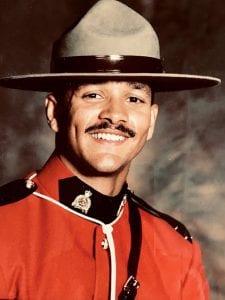

Alain Babineau, 59, had to fight to become a police officer. The first time he applied to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in 1981, the interviewer asked him how he would respond to being called the N-word. He tried to put up a brave front, saying the slur was nothing he hadn’t heard before. He was also asked about marijuana use and gave an honest answer: he had once tried cannabis, but it didn’t interest him. He didn’t get the job.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

On his second attempt a few years later, he wasn’t hired again. Eventually, he was told he had been rejected because the RCMP concluded he lied about his history with drugs (he says an access-to-information request showed they didn’t even have any evidence). After he filed a human rights complaint, the RCMP re-interviewed him and offered him a position in 1988. As a narcotics officer in Toronto, he faced many microagressions (his superior often called him “Black man”). “What do you do when you’re a recruit, you’re a newcomer, you’re trying to fit in?” Babineau asks. “You shut up and put up.”

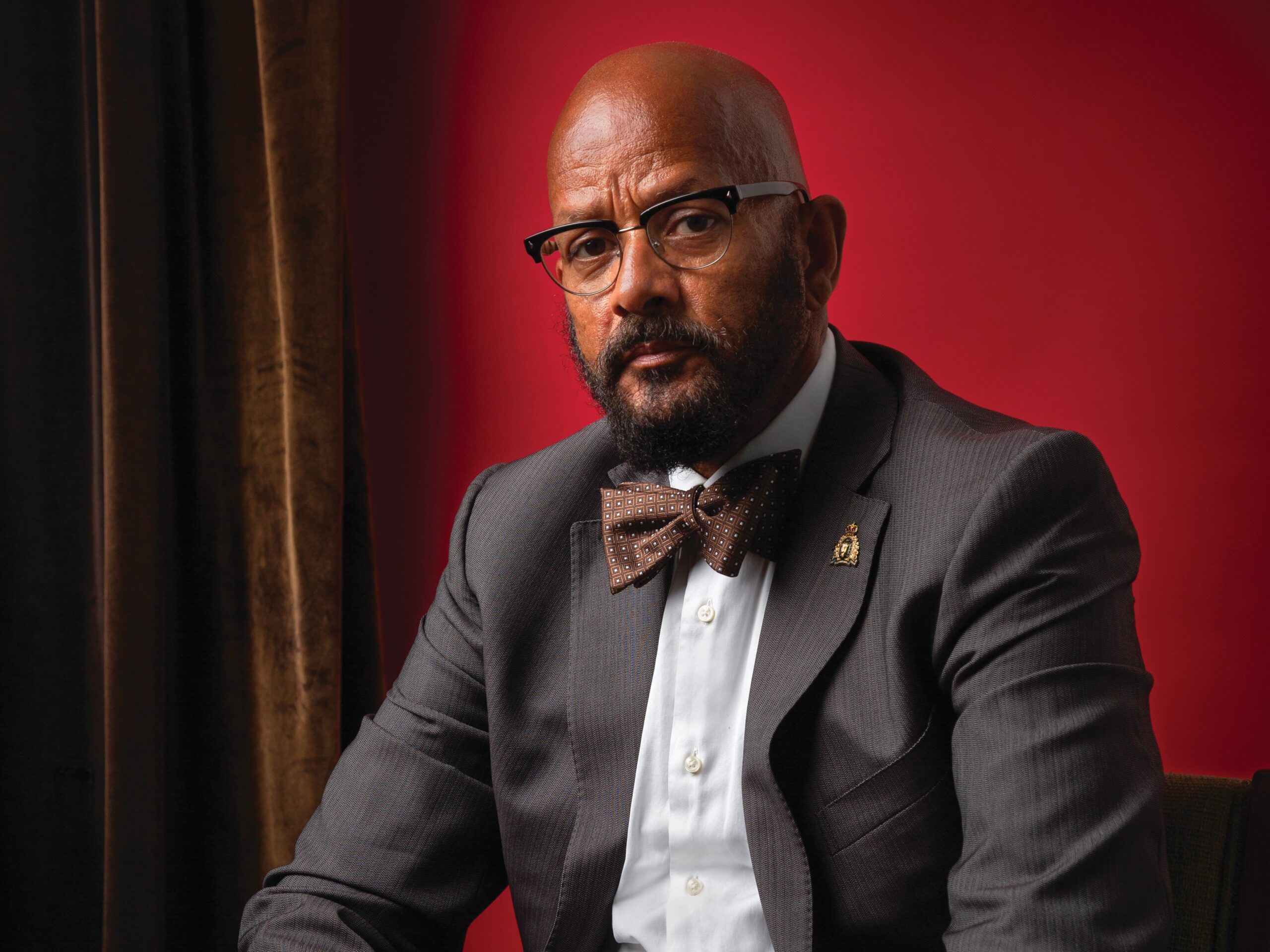

After 27 years with the force, Babineau retired in 2016 and completed a law degree. Today, he is an adviser for the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations. He also offers police training on ethics, race relations and racial profiling through his consulting firm. He spoke to Aleysha Haniff from his home in Montreal.

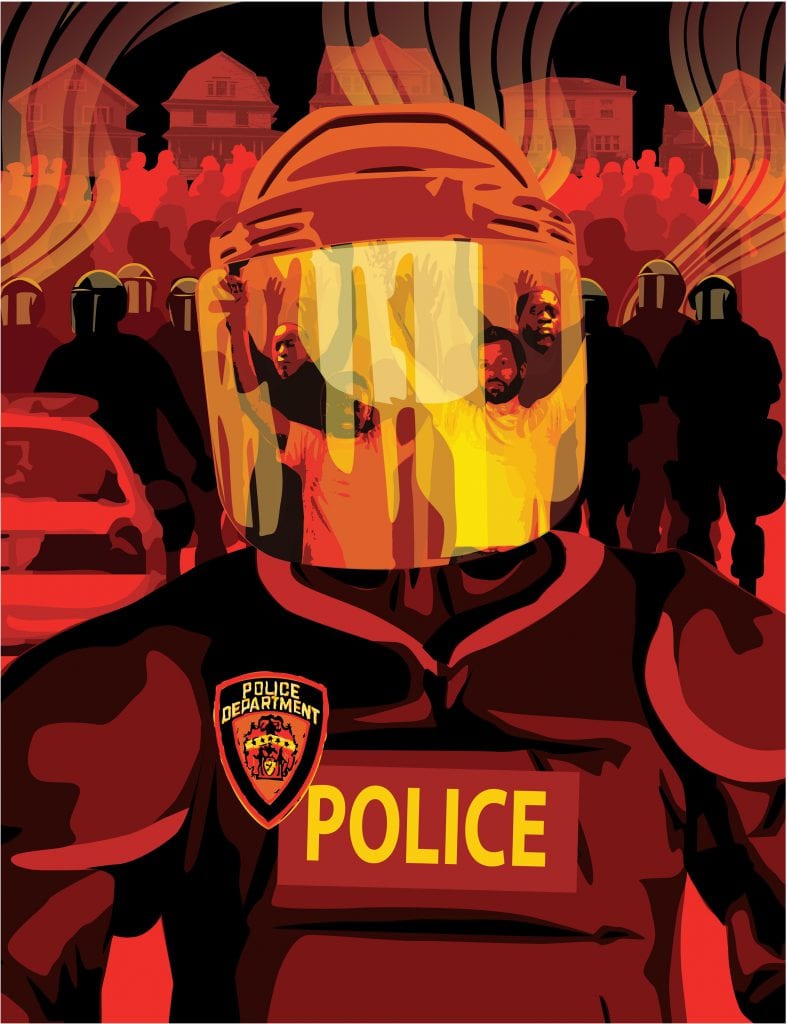

Aleysha Haniff: Black Lives Matter, police brutality and systemic racism are at the forefront of public and political attention in the wake of George Floyd’s killing by Minneapolis police in May. What do you think makes this moment different from previous calls for change?

Alain Babineau: I think it is COVID. People were cooped up at home, having nothing to do, and they were forced to watch the internet, watch video clips, and they saw somebody lose his life in front of their very eyes. And it’s not just people of colour; white people have joined this movement. I mean, is this the first video of a Black man being beaten, killed, shot in the back? No, those videos have been there all the time.

AH: After Floyd’s death, some police officers responded to anti-racism demonstrations by taking a knee. What else can police do?

AB: Don’t take a knee. Take a stand. Take a stand against racist jokes. Take a stand against policies that are racist. Change your policy, change your culture. Admit that systemic discrimination exists within the police force, and dedicate the rest of your career to change. Taking a knee is meaningless if you beat somebody up the next day.

AH: After saying that she “struggled” to define systemic racism, RCMP commissioner Brenda Lucki admitted that it does exist in the service. Did you witness systemic racism during your career?

AB: Of course. Throughout my whole service in various ways, not just systemic but implicit and explicit racism and discrimination. Systemically, it’s fraught from recruiting to pension.

The way the recruiting system is designed, even though it has improved, it’s not really appealing to racialized groups. Interviewers are mostly white males, some females, but mostly white. Sometimes an applicant’s accent turns somebody off. The whole hiring process is a perfect example of systemic racism because it is informed by the views and perspective of the white majority.

AH: Was overt racism ever directed at you?

AB: Internally, it would be pretty stupid for someone to verbally express racism. That would be career suicide. But there are all kinds of innuendoes. Every time someone of colour gets a promotion, there are comments: “Maybe they had to promote the minority.” Of course, you hear racist comments from time to time toward people in the community. That is pretty standard. It’s guarded more than when I first started, but it’s still there. The needle hasn’t budged a whole lot.

More on Broadview:

- Is George Floyd’s death the start of my daughter’s ‘Black list’?

- Microaggressions are constant reminders that I don’t belong

- 5 resources to help you become a better ally to Black people

AH: In Canada, racism against Indigenous people is also an issue. What did you see?

AB: The RCMP, for over 100 years, has been involved negatively with Indigenous communities. It becomes part of the system in how police think about racialized minorities. When you’re a police officer and you come from a society that looks upon Indigenous people as less than — let’s call it what it is, that’s how they look at them — it’s stereotypes. If we believe Black people are violent and more prone to criminality, we will over-police an area. We collect data based on this over-policing and over-scrutinizing, and then we use data to say, “See? Told you they’re bad.”

AH: There are increasing calls to defund the police. Is this feasible?

AB: What does that really mean, defunding the police? These are fighting words for the police — over 80 percent of policing budgets go toward salaries and benefits. Why does the money have to come from the police? I haven’t heard the answer to that, except that we need to punish them because they’ve been misbehaving long enough. News flash to everybody: criminals exist. Other programs need to be looked at too, because maybe they’re not working so well. So why don’t we take money from those programs and put them in mental health and social services? I don’t believe in defunding the police, because it’s a fad, in my opinion. But we certainly need to change the culture.

AH: Do you think more can be done to help officers learn to de-escalate?

AB: Training is 100 percent. I always tell police officers, “You have a small window of opportunity to de-escalate a situation.” At the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations, we see a lot of cases where we help people file police complaints. But when you look at the case, it could have been solved if the police officer had taken an extra two minutes to talk to the person appropriately and with respect.

Sometimes the officer’s reaction is pride, arrogance and racism all mixed together. And people end up face first on the ground, handcuffed and either tasered or pepper sprayed for having turned left while they indicated right. De-escalation techniques should be bread and butter in policing, but unfortunately they would much rather train people with long guns and how to shoot. That’s a cultural shift that needs to happen.

AH: You mentioned that the needle hasn’t budged much in terms of racism within law enforcement. Why do you think that is?

AB: The culture hasn’t changed a whole lot. That’s number one. And then number two with respect to how we deal with communities of colour, we still have those stereotypes. We still have those views of who the criminals are and how we should deal with them. Internally, folks don’t want things to change because they’ve dominated the institution for years.

AH: The House of Commons committee on public safety is studying systemic racism in policing, but this has been criticized as a stalling tactic.

AB: It’s not a stalling tactic, but the very nature of those committees and studies are so lengthy in time. At the end, you get some recommendations — we call them “calls for action” now — which may or may not be implemented. What else do you need to study? How much more? There’s been all kinds of reports right across Canada on systemic racism since the 1980s. Don’t be studying the problem for which you’ve been provided answers for decades.

AH: You still have your hand in law enforcement. What inspires you to continue your work?

AB: I’ve always wanted to be a cop. So I always felt that this is a great profession. And it’s very rewarding. Now my goal is to make it better, make it the way in which it was intended to be. Some claim that policing is there to beat people up and kill people. That is not the way modern policing was intended to be. Over the years, some police officers began to see themselves as warriors and protectors against crime, as opposed to guardians and servants of the community. And so we need to find that balance.

The majority of people are good. They don’t deserve to be treated disrespectfully; they don’t deserve to be beaten up. That’s not why we joined the police. And so my mission now is not to eradicate bad apples, so to speak, because I don’t think it’ll ever happen. But I think we can change systems. We can change culture to mitigate the risk of those people infecting others.

This interview first appeared in Broadview’s October 2020 issue with the title “Don’t take a knee. Take a stand.”

***

Aleysha Haniff is Broadview’s assistant digital editor.

I hope you found this Broadview article engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

This individual has stated in the past that he doesn’t tell anyone he was a police officer but worked for the government. I don’t see that pin on his lapel saying GOVERNMENT. Show me where he complained via documentations? One’s perception is one’s belief.