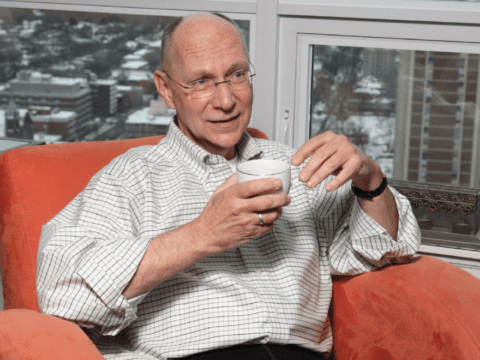

Jim Chapman can still remember his euphoria the day he ran his first mile around the track at the local gym in London, Ont. The elation was so strong that he did a victory circuit of all the other machines he usually worked out on just to celebrate the milestone — plus as many extra sets as he figured he could push his 50-year-old body to do.

He’d just finished the last machine — doing 35 abdominal crunches instead of his usual 25 — and rested his head back on the mat when he felt a crushing pressure on his chest. And then pain.

His family is riddled with heart disease and he’s a savvy fellow, so it occurred to him as he lay there that he might be dying. He wasn’t afraid. But he was fascinated and started to take notes in his head, an old journalist’s trick he’s used for years in his career as a radio personality and reporter.

Near-death experiences used to be considered flaky. Delusion, hallucination, invention, satanic possession or even psychosis, the thinking went. Today, near-death experiences are under serious investigation by neuroscientists, medical doctors and quantum physicists, who are examining whether they are a legitimate laboratory for uncovering the nature of human consciousness. And even for exploring life after death. This research could have profound implications for people of faith everywhere.

The interest is so novel and intense that in 2008, researchers went to the United Nations in New York to announce the launch of the world’s first large international study on near-death experiences and on whether they provide clues about what happens after death.

That study — known as AWARE, or AWAreness during REsuscitation — is now under way at 25 hospitals, one in Montreal and the rest scattered throughout the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States. The lead researcher is Sam Parnia, a neuroscientist based at the University of Southampton. His Canadian colleague is the neuroscientist Mario Beauregard of the University of Montreal.

The basic question is this: How do our sense of self-awareness and our subjective thoughts, feelings and emotions — the things that make us uniquely, individually human — show up in the brain? Do the brain cells construct them or just process them? If they just process them, then where do they come from?

Dr. Parnia calls this “one of the most profound questions facing science today.” So his study looks at the growing number of people who, with medical advances, are revived after dying from heart attacks. These people are clinically dead for several minutes to as long as an hour — no breath, no pulse, no brain activity — yet some come back with lucid, well-structured tales of where they have been and what they have observed.

Between 10 and 20 percent of the resuscitated report these near-death experiences, and they’re remarkably similar, regardless of the survivor’s age, sex, nationality or religious background. Reports of these extraordinarily similar experiences stretch back through culture, time and the written human record.

Some of the stories show evidence of reasoning and include accurate details of how the clinically dead were resuscitated or of conversations the medical staff had while the resuscitation was taking place. A famous case is the man who told his doctor the serial number on the paddles that revived him. The doctor, baffled, checked the number and found it was correct.

The AWARE study will test this phenomenon by placing randomly generated, emotionally resonant images at high heights in emergency resuscitation rooms around the world, invisible to those standing in the room. Researchers will then interview the revived to find out whether they saw the images during out-of-body experiences.

But if the brain is dead, how is it reasoning and laying down memories? Could it be that human consciousness exists apart from the machine of the body?

Chapman started his note-taking with the details. The blanket the emergency workers wrapped around him in the gym was scratchy. One ambulance attendant was very young and the other rather brusque. Once they got to the hospital, he tracked the sound of the nurses’ squeaky shoes on the floor. The guy in the bed down the hall was screaming.

Machines were buzzing and beeping.

Lying on the gurney, he started interviewing the nurse and then the doctor, taking mental notes the whole time. All of a sudden, he felt strange and told the doctor he was feeling terrible. Then, overwhelmed with tiredness, he shut his eyes, thinking he’d collect his thoughts and finish the interviews later. Then everything went eerily quiet. No buzzes. No screaming. No squeaky shoes. He thought the power must have failed.

“When I opened my eyes, I was not in the emergency room,” he says. “I was standing at the edge of a valley that was sloping toward a stream. There was a calm breeze. But the foliage wasn’t green. It was brown — not a dried-up brown, but just brown instead of green….It popped into my head: ‘I’ve died. They’ve lost me.’ And I said, ‘This is a different place, another reality. I wonder what will happen now? What am I supposed to do now?’”

The turning point in the medical and scientific investigation of near-death experiences came in 1975 when the medical philosopher Raymond Moody wrote the bestseller Life After Life, in which he recounts the tales of hundreds of survivors and coins the term “near-death experiences.” Those accounts were eerily alike, and the similarities have held up in further studies of other survivors.

Frequently, the person who was dying reports rising above their body and floating in the air, often watching the attempts at revival. The survivors said they tended to pass down a tunnel and move toward light. Some said they met relatives who were already dead, heard otherworldly music or had the sense of being in an alternate, beautiful world where they were accepted unconditionally and felt part of a larger whole.

Sometimes, they described a life review, in which a being or creature or force went through events in the dead one’s life and assessed them or explained them. At times, the creature explained big questions of how the cosmos works or other inscrutable concepts.

Most of the dead who came back described feelings of intense peace, even bliss. They often did not want to come back but were obliged to. A very few described an unpleasant experience. And most of the returned felt changed for the better, becoming happier, calmer and less materialistic.

Early written examples of what may be after-death experiences are the myth of Er told in Plato’s Republic and the tale of Gilgamesh. Similar stories appear in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, in the records of Chinese and Japanese Amida Buddhists and in the tales of inhabitants of Papua New Guinea, among many other cultures.

The 19th-century adventurer Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, the 20th-century polar explorer Admiral Richard Byrd, the writer Somerset Maugham and the early psychologist Carl Jung talked about their own near-death experiences. Collections of first-hand accounts began to be published as early as 1892, all describing what have become the classical elements of the near-death experience.

Today, more than 2,000 people from around the world have told their tales in detail on the website www.nderf.org, part of a research foundation set up by the Louisiana-based radiation oncologist and near-death expert Jeffrey Long as an archive of the events and the biggest site on this topic in the world.

“People really want to know what happens when we die,” Dr. Long says. “It’s the primordial question of life.”

Chapman started to feel a tingling warmth at the bottom of his feet. A few metres away through a shimmering haze, he saw his family looking very sad and felt he’d abandoned them. But then he thought, “They love each other, and they’ll take care of each other.”

Right after that, he was filled with the sense that he was surrounded by something. Then he had the feeling that hundreds of creatures or even more were surrounding him, welcoming him. He was there and was everywhere at the same time.

“I had the feeling that I was coming home in the most profound sense,” he says. “I had the sense that I was where I needed to be and where I would be cared for, that I was one of them. I had the most incredible feeling of being loved and welcomed.”

All of a sudden, he felt he’d been given all sorts of insights into his life. He realized, for one thing, that he’d worked too hard without a proper purpose. Then he thought, “I know I’m dead. What do I do now?”

“And I started to feel annoyed. I thought, ‘Shouldn’t I be going somewhere?’ and I remembered hearing things about tunnels and lights — which I would have shrugged off before — so I started to look for a tunnel or a cave or a door. And then up across the valley, there was a very bright light. So I started to walk toward the light, because that’s what people do.

“I was walking down to the valley, and the creek looked oily. And I almost got there and I thought, ‘Is it okay to get my feet wet?’ . . . And then a young woman appeared. I looked ahead, and there was her face in front of me. And I stopped and I remember thinking, ‘What if she doesn’t speak English? Is that a problem?’ And I wrote it in my notebook.

“And then a voice yelled, ‘Mr. Chapman, are you in there?’ And I opened my eyes, and there was the same face and she was the nurse. They’d been paddling me [with defibrillators] for several minutes. And they’d decided to give me one more shot. And there I was, back in the ER.”

Chapman had been clinically dead in cardiac arrest for nearly three-and-a-half minutes, with no brainwave activity, no pulse, no breath.

Since Moody’s book came out in 1975, hundreds of academic papers on near-death experiences have been published in many of the world’s most prestigious journals. Many have suggested medical theories. The most popular are that the experiences are induced by the brain’s own chemicals produced under distress, or by too little oxygen or too much carbon dioxide in the brain, or by stimulation of the temporal lobe region of the brain’s cerebral cortex, or by drugs, such as painkillers, administered in the emergency room.

The hitches with these theories centre on the fact that none of them can explain every near-death experience. Drugs, for example, seem to inhibit memories of near-death experiences, not produce them. Plus, some near-death experiences happen when no drugs or doctors are present, like when a climber falls off a cliff and survives.

More importantly, though, the medical theories don’t explain how a person can observe and remember events while unconscious or clinically dead. Yet four recent major studies have shown that the unconscious or clinically dead are seeing things while their brains show no activity, and their recollections are accurate down to fine detail. Strikingly, the experiences start at the time of unconsciousness, Dr. Long notes.

One case that amazes him is the story of Vickie, a professional singer he interviewed who had been blind from birth. The first time she had sight was in her 20s during a near-death experience after a car crash, when she saw her body from above in the emergency room.

She recovered and is still blind. But, like others who have had near-death experiences, she saw in 360 degrees all at the same time, rather than in the pie shape that the human eye is capable of taking in. To this day, she doesn’t understand how humans can’t see across all 360 degrees at the same time.

“Obviously, this is medically inexplicable,” says Dr. Long, author of the 2010 book Evidence of the Afterlife: The Science of the Near-Death Experience. “It’s occurring independent of brain function.”

He has become convinced through his research that near-death experiences describe a physical reality, possibly in another dimension, that exists and that the human brain only poorly understands. “There is a scientific principle that what is real is consistently observed,” he says.

For Dr. Beauregard, the Montreal neuroscientist involved with the AWARE project, the research leads to, of all things, quantum physics. He and others wrote a paper in 2004 in the eminent journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B talking about the need to apply the principles of quantum physics theory to brain research. In a nutshell, this means understanding that the world is not just what happens mechanically and can be observed and described but is also influenced by human experience and consciousness. So what we think influences what is.

What does this theory mean for understanding near-death experiences? It opens up the possibility that human consciousness may be a scientific entity in its own right. “The psyche cannot be reduced to a physical realm,” Dr. Beauregard said in a 2008 lecture.

That would mean spirituality is “an objective branch of knowledge with its own laws, theorems and axioms,” as one of Dr. Parnia’s papers says. Some academics have suggested that near-death experiences among early humans have infused all faith systems over time. It’s a tantalizing but disurbing thought to some theologians.

“I’ve always had a certain distrust of the kind of spirituality that finds evidence of God outside faith,” says Douglas John Hall, professor emeritus of Christian theology at McGill University in Montreal. “I would find it difficult to say that there will come a time when faith isn’t necessary anymore because we’ve got science.”

Chapman, now 61, has done a lot of thinking since he died. He wrote the book Come Back to Life in 2006 and has spoken to an estimated 100,000 people about what he went through. And he’s come to some conclusions.

“It wouldn’t surprise me to find out there is another reality, another physical explanation,” he says.

He is absolutely convinced that the human spirit exists. “I’m not just a body. The older I get, the more I become aware that this flesh-and-blood machine carries my consciousness around.”

That spirit, he says, “is a transcendent spirit, and its instincts are for good. It wants and strives to be good. It is a positive part of this cosmic whole.”

Raised in the United Church — Trinity United in London, Ont., was his childhood congregation — Chapman no longer talks about religion and does not regularly attend church.

Instead, he talks about God. And it has little to do with churches, dogma and holy books, he says. To him, these are just manifestations of the God he has already encountered.

“I did not see God. I experienced God. There were no pearly gates,” he says.

And when he dies again?

“At the end of this life cycle, I have every confidence that I will be back at that placeof home. I was given to understand that’s what will happen. And I hope it will happen for everyone.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s November 2010 issue with the title “To the brink and back.”