In six years, Broadview will celebrate the beginning of its third century as a Canadian publication focused on spirituality and religion. The magazine has a record of unbroken publication that goes back farther than any other English-language magazine in North America. One of Broadview’s most pressing issues is its relationship to Indigenous communities in Canada and its responsibility to participate in reconciliation. So it’s vital to look back and ask: what were its beginnings? What is its legacy regarding colonialism, settler-Indigenous relations and faith?

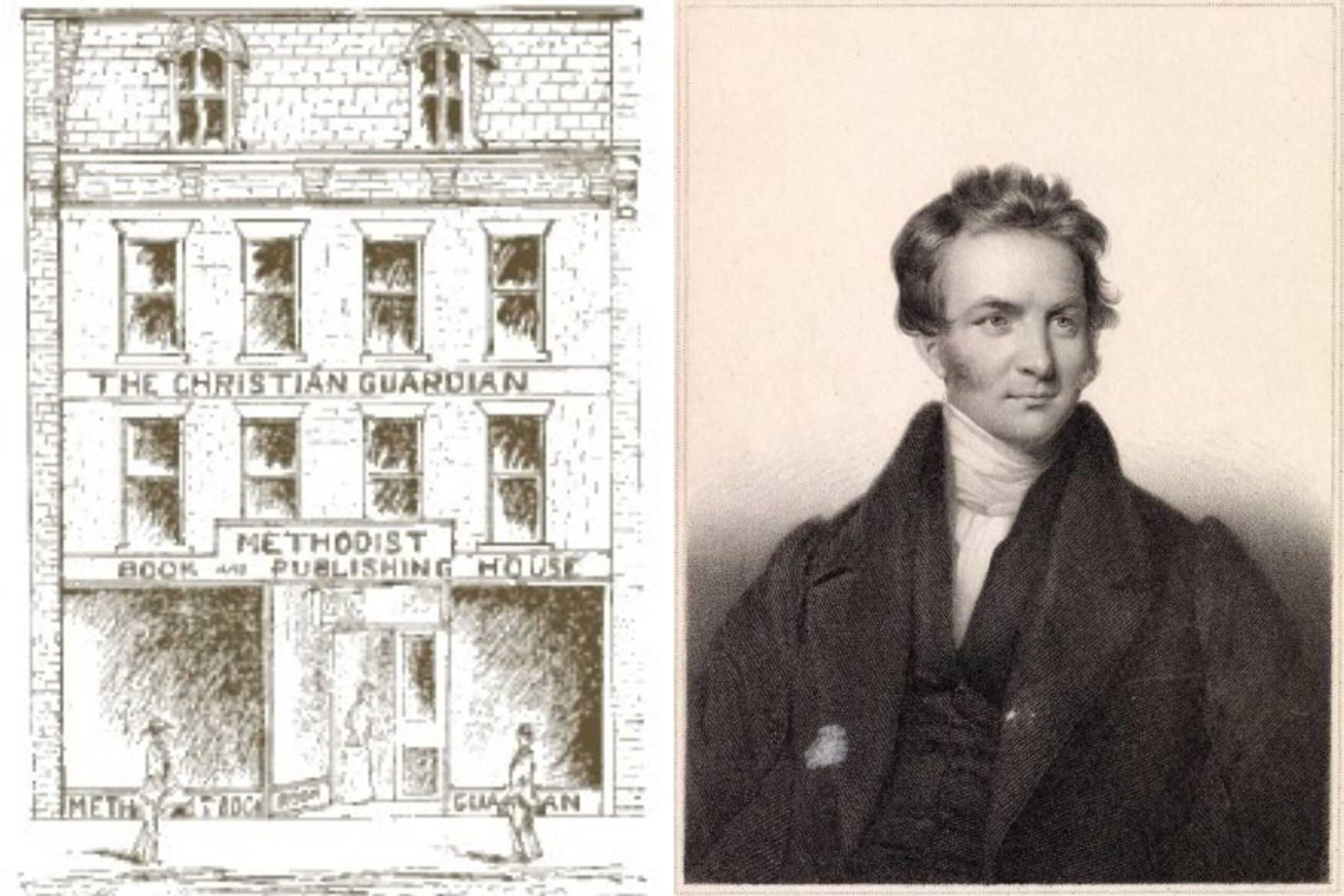

The publication’s early days show a mixed legacy. Begun in 1829 with the title The Christian Guardian, the then-weekly paper was initially a voice for the new Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada. A close look at the Christian Guardian offers a unique glimpse into settler motives and the spiritual outlook of Indigenous people at the time.

Methodism, missions and myths in The Christian Guardian

The first edition of The Christian Guardian was printed on Nov. 21, 1829. At its helm was Egerton Ryerson, the paper’s 26-year-old founding editor. Ryerson was hugely respected by his fellow Methodists for how he used his quick wit and breadth of knowledge to challenge government authorities and Anglican church, which was then the official, government-funded church of Upper Canada.

Once held in high esteem as the founder of public education in Canada, Ryerson’s legacy has been called into question because of the ways in which later generations used some of his ideas to create the genocidal residential school system. His complicated legacy is reflected in the pages of the publication he edited.

Throughout his life, Ryerson was an ardent Methodist, and the paper he edited in early adulthood was Methodism’s most effective mouthpiece in Canada.

But there’s a sense in which the language and values of 19th-century Upper Canada are foreign to us today.

“Reading The Christian Guardian is like reading another language,” says Donald Smith, professor emeritus of history at the University of Calgary. Smith has scoured its pages over an academic career spanning 50 years.

Part of the strangeness, he says, comes from a different cultural context — social Darwinism hadn’t yet created a pseudo-scientific hierarchy of human races, so Christian Guardian readers did not have the same consciousness of race that readers of Broadview do today. Instead of skin colour, for example, religion and culture were reserved for the harshest discrimination. Part of the Christian Guardian’s strangeness comes from a pietistic religious perspective “that is very hard to relate to today,” Smith says. Along with a somewhat literal belief in heaven and hell, pietism emphasized religious feeling and strict adherence to spiritual practices such as prayer, Bible study and congregational worship.

By the early 1800s, much of the energy for the Methodist church, a religious movement newly arrived in Upper Canada, came from missions. For Anglo-Methodists, missions seen as a way to not only make converts but also to improve the lives of people in the immediate community and around the world in places as far off as China and India.

Almost as soon as The Christian Guardian started rolling off the presses, Indigenous people featured prominently. More than eight percent of the content published in its first year was dedicated to Indigenous missions. Much of what was published reflected negative settler stereotypes. Indigenous ways of life were characterized as inferior and needing improvement, for example, exchanging what writers described as “smoky” bark wigwams for the “civilized” homes of white settler Christians.

These negative images were mixed with more positive accounts of what we now call the trope of the “noble savage” — romanticized depictions of Indigenous people that have little to do with who they actually are and how they live. But even these idealized depictions were the product of settler stereotypes. Contemporary Indigenous commentators such as Thomas King say that both positive and negative stereotypes, then as now, are almost always connected to settler feelings of insecurity in their new home and their desire to acquire more land for their exclusive use. Two-dimensional Indigenous characters, good or bad, are easily dismissed and put out of mind. These stereotypes allow settlers to maintain their own fantasy that they are the only ones sophisticated enough to survive in the modern world.

There was a prophetic understanding of community and justice struggling to emerge from Canadian Methodism. But some of the most compelling work in this regard was done by Indigenous people themselves.

The Christian Guardian also published strong words in defence of Indigenous people’s rights in the colony, including their right to hold onto their land.

Clearly, there was a prophetic understanding of community and justice struggling to emerge from Canadian Methodism. But some of the most compelling work in this regard was done by Indigenous people themselves.

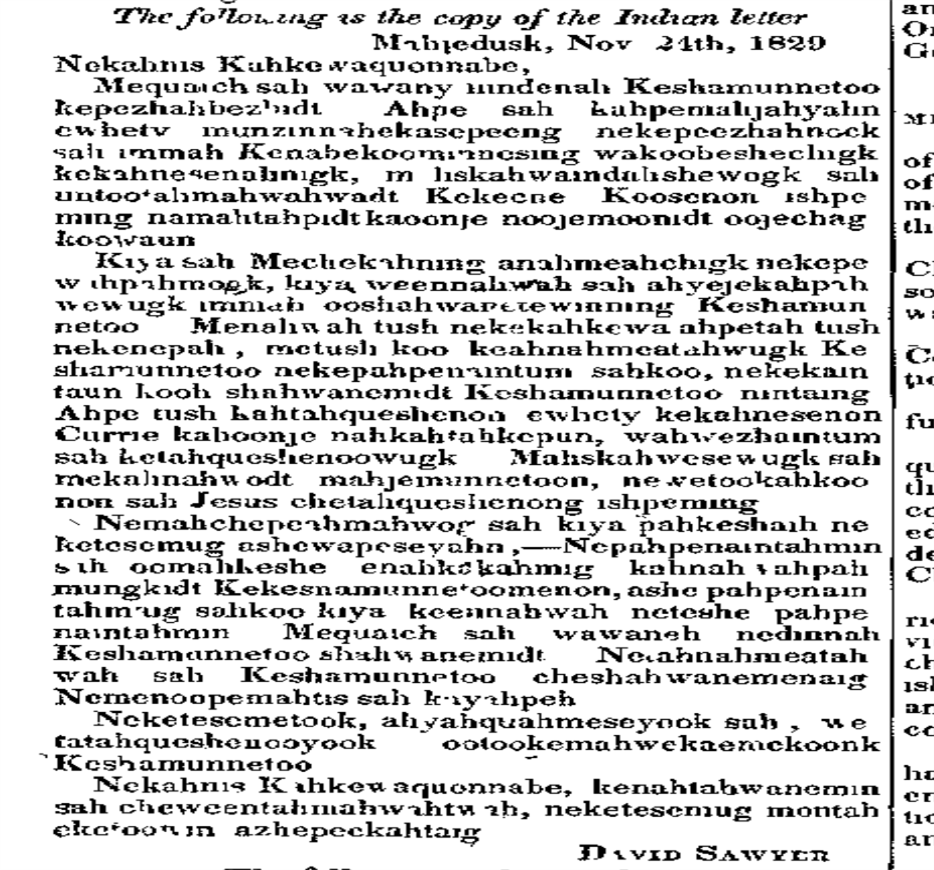

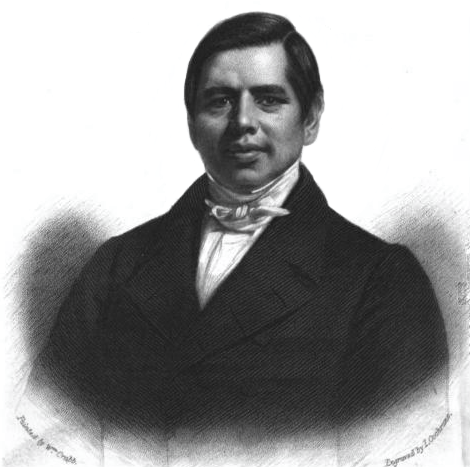

Almost two-fifths of The Christian Guardian’s content about Indigenous people was written by Indigenous authors — that is, roughly three percent of the publication’s total printed words in its first year. These authors included Kahkewaquonaby (Peter Jones), John Sunday, John Paul, and David Sawyer.

Indigenous readers and contributors

If settlers weren’t the only ones writing for The Christian Guardian, neither were they the only ones reading it. Peter Jacobs, an Indigenous Christian who learned to read and write in both English and Anishinaabemowin in a Methodist mission school, was one of the publication’s first subscribers. In a letter to the editor printed in 1830, Jacobs wrote about how the magazine meant a lot to him and to his community. “When I get your good writing talk every week, then comes a good many of our brothers to hear the good news,” he wrote, “so I read and interpret it unto them in our talk.”

And what did Indigenous writers have to say? They used their space to assert their leadership in the church and society. At least 17 different Indigenous church leaders, all male, are listed in their contributions to The Christian Guardian. First among them was Kahkewaquonaby, otherwise known as Peter Jones, who was both a chief of the Mississaugas of the Credit and an ordained Methodist minister. Dorcas societies, associations inspired by a woman in the early church, are also mentioned. These were places where Indigenous women could take the lead, barred as they were from ordained ministry.

More on Broadview:

- What my friend Rev. Vivian Seegers taught me about helping, healing and finding joy amidst pain

- Why more Indigenous people are leaving Christianity

- Ministers explain the problem with the word ‘mission’

Indigenous evangelists, both male and female, persuaded many Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee people to join the church in Upper Canada. By 1832, Indigenous people made up 7.2 percent of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s total membership compared to 4.7 percent of the entire population of Upper Canada.

Indigenous people also used the Methodist magazine to promote their culture and language. The Christian Guardian may have been the first ever to publish a letter written in Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Anishinaabeg. It was a sign for some that Anishinaabemowin could be on par with English in the new colony.

Indigenous children were learning to read and write in their own languages at Methodist-supported schools in their own communities in the 1820s. Indigenous contributors referred to God as the “Keshamunnetoo” (Gitchi Manidoo) or Great Spirit.

Although all the Indigenous contributors to The Christian Guardian were Christian, their stories often relayed the ideas of Indigenous people who had different spiritual points of view. Some, like Chief Pah Zhe Ke Sech Quash Kum at St. Clair River, acknowledged that the Great Spirit made all people. The Great Spirit, he said, gave the “white man his way of worship, written in a book, and prepared a place for his soul above,” whereas “[w]hen the Great Spirit made the Indian, he gave him instructions in regard to his way of worship, and mode of administering medicine, altogether different from that of the white man.”

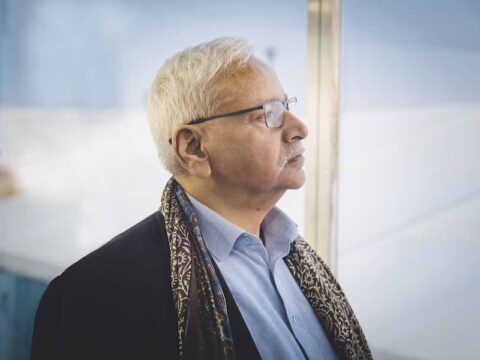

Below: Jonathan Hamilton-Diabo, a professor of theology at Emmanuel College, reads Chief Pah Zhe Ke Sech Quash Kum’s words from the Feb. 27, 1830 edition of The Christian Guardian

“Brothers,” The Christian Guardian’s Indigenous contributor reports Chief Pah Zhe Ke Sech Quash Kum to have said, “I am glad to see you as brothers, but I will not become a Christian. This is all I say.”

Chief Snake of Muncey, Ont., held another view. He told Indigenous missionaries, “We take hold of the white man’s worship with one hand, but with the other hand we hold fast to our fathers’ worship.” Contrary to what settler missionaries were teaching, for this chief at least, Christian and Indigenous teachings and practices were complementary. In fact, many Indigenous people carried both spiritual teachings inside them even if they became Christian, a duality they often only shared with those they trusted.

Below: Rev. Murray Pruden, The United Church of Canada’s national executive minister for Indigenous ministries and justice, reads an address from Captain Snake that appeared in the June 5, 1830 edition of The Christian Guardian

Broadview’s legacy today

Why is this legacy important to know today? For one thing, the history coming to light about church-run residential schools in Canada makes many wonder whether being Christian and Indigenous are incompatible.

Rt. Rev. Carmen Lansdowne, moderator of The United Church of Canada, says she was surprised to learn of the early Indigenous voices in The Christian Guardian, but that she knew of similar stories of people finding different ways of relating their traditional Indigenous beliefs and practices with Christianity among her own Heiltsuk people on the west coast of Canada. She said that in the early 1800s, it was probably a lot easier to hold together Christian and Indigenous identities because the Indian Act and residential schools — some of the worst settler attacks against Indigenous people and their culture — had yet to take place. But exclusive understandings of religion are not and have never been the Indigenous way, she says.

Since her ordination in 2007, Lansdowne has witnessed a healthy and life-giving exchange of ideas. “Where some of that exclusivity of the [settler] Christian tradition has taken root in [Indigenous] communities, people are changing,” she says.

For Jonathan Hamilton-Diabo, a professor of theology at Emmanuel College in Toronto, Christian faith was simply a part of life growing up in Kahnawake. It wasn’t until his wife pushed him to confront the realities of residential schools that he started to question the relationship between his Indigeneity and Christianity. “I had a question posed to me,” Hamilton-Diabo remembers:

“It was like ‘How can you be Mohawk and Catholic?’ And I think it was the first time the question ever occurred to me.”

“Where some of that exclusivity of the [settler] Christian tradition has taken root in [Indigenous] communities, people are changing.”

Rt. Rev. Carmen Lansdowne

But, as he began to work on it, it started to dawn on him that Indigenous Christians not only had a place in the religion but had something unique to contribute to it. “Indigenous perspectives can influence Christianity in such a good way.”

Hamilton-Diabo says, “Indigenous perspectives [now have] a valid place within these discussions that it never used to.”

Broadview’s history helps us to see that Indigenous insights into Christian faith are not new but a contribution that settlers have neglected for a long time. As a non-Indigenous person, I am grateful for the record that Indigenous Christians left in Broadview’s predecessor, The Christian Guardian. Among other things, it shows that amid the bleak history of colonial violence perpetrated by settler Christians against Indigenous peoples, there is a truth and a spiritual community that was always bigger than the colonial mentality could grasp.

EDITOR’S NOTE 8/1/2023: This story has been extensively updated to reflect the contributions of a sensitivity reader, and to add some additional historical details and some further editing.

***

Rev. David Kim-Cragg is a minister at St. Matthew’s United in Richmond Hill, Ont.

Vanessa Kennedy, who served as a sensitivity reader for this article, is an Indigenous consultant in Hillsdale, Ont.

THE PERIGOE FUND: This feature was funded through a generous gift from Revs. John and Lillian Perigoe to support Broadview’s coverage of Indigenous issues.

thank you for this very enlightening perspective, David.

Thank you for showing us more about our past. It is important to see who was writing and reading the Christian Guardian and how indigenous views were presented.

I have a concern: you called Ryerson the “architect of residential schools”. This makes it sound like he was responsible for all of the ills of residential schools which is untrue.

Ryerson’s 1847 report said about residential schools that “their object is identical with that of every good common school”. He did not recommend that residential schools to be underfunded. He did not recommend that children be underfed and poorly housed. He did not recommend that children be sexually exploited. He did not recommend letting children die of untreated disease. He did not recommend forcibly removing children from their families at gunpoint. The blame for these and other failings rests with the Government of Canada and the churches that ran the residential schools.

Further, the residential school system didn’t really get going until about 1890, more than 40 years after Ryerson’s report and 8 years after he died. The residential school system peaked at about 80 schools and 110,000 students, but it was people other than Ryerson who made that happen.

Hi Derek, thanks for your comment. We did not call him “the” architect of residential schools, but “an” architect. A proposal that he wrote became the framework for residential schools, so his ideas were certainly influential in their creation. The wording does not imply that he was responsible for how residential schools were conducted. Best, Emma

What a friend we have in Jesus, the living eternal Christ is Indigenous. Christianity evolved after he walked this earth. The “Indian Act” was the source of all the woes of God’s children. Jesus gave us the good news, it is up to us to learn it, live it and be happy. God bless you and may the Holy Spirit rest in you, all the days of your life and all eternity.