On a brisk day in late May 2019, Chiamaka Okoli decided to go for a walk with her young son along the tree-lined streets of their Waterloo, Ont., neighbourhood. The 20-minute excursion had become a daily occurrence after her recovery from a near-fatal aneurysm the year before. But this time, the 31-year-old did not make it back to their third-floor apartment.

Later that day, at a scrap metal recycling company where he worked in shipping and receiving, Chiamaka’s husband, Felix Okoli, ignored a phone call. Not long after, his boss summoned him into his office and offered Felix a phone. On the other end of the line, a police officer told Felix that his 21-month-old son, Munachi, was with Family and Children’s Services and needed to be picked up. Felix was confused; he had left Munachi with his wife at home that morning. Why would he be anywhere but with Chiamaka?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In the car, Felix’s phone rang again. Someone from Grand River Hospital told him to come right away. Felix tried to explain about his son. The person reassured Felix that they would call the police and have them bring Munachi to him. All he needed to do was get to the hospital. Felix turned his car around and began driving toward Grand River.

Once there, Felix was ushered into the ICU and saw his wife on life support. He learned that on her walk, Chiamaka had fallen and someone called an ambulance. Now hospital staff were telling him that a CT scan had shown a fresh pool of blood in her brain. They didn’t know if her aneurysm had bled again or if a different part of her brain was bleeding. Either way, it didn’t look good. “At that moment, I wasn’t myself. I was devastated,” says Felix.

More on Broadview:

- 3 misconceptions about grief

- I turned to art to mourn my dad, the Anishinaabe man I never knew

- A DNA test brought me a loving brother, but also more questions

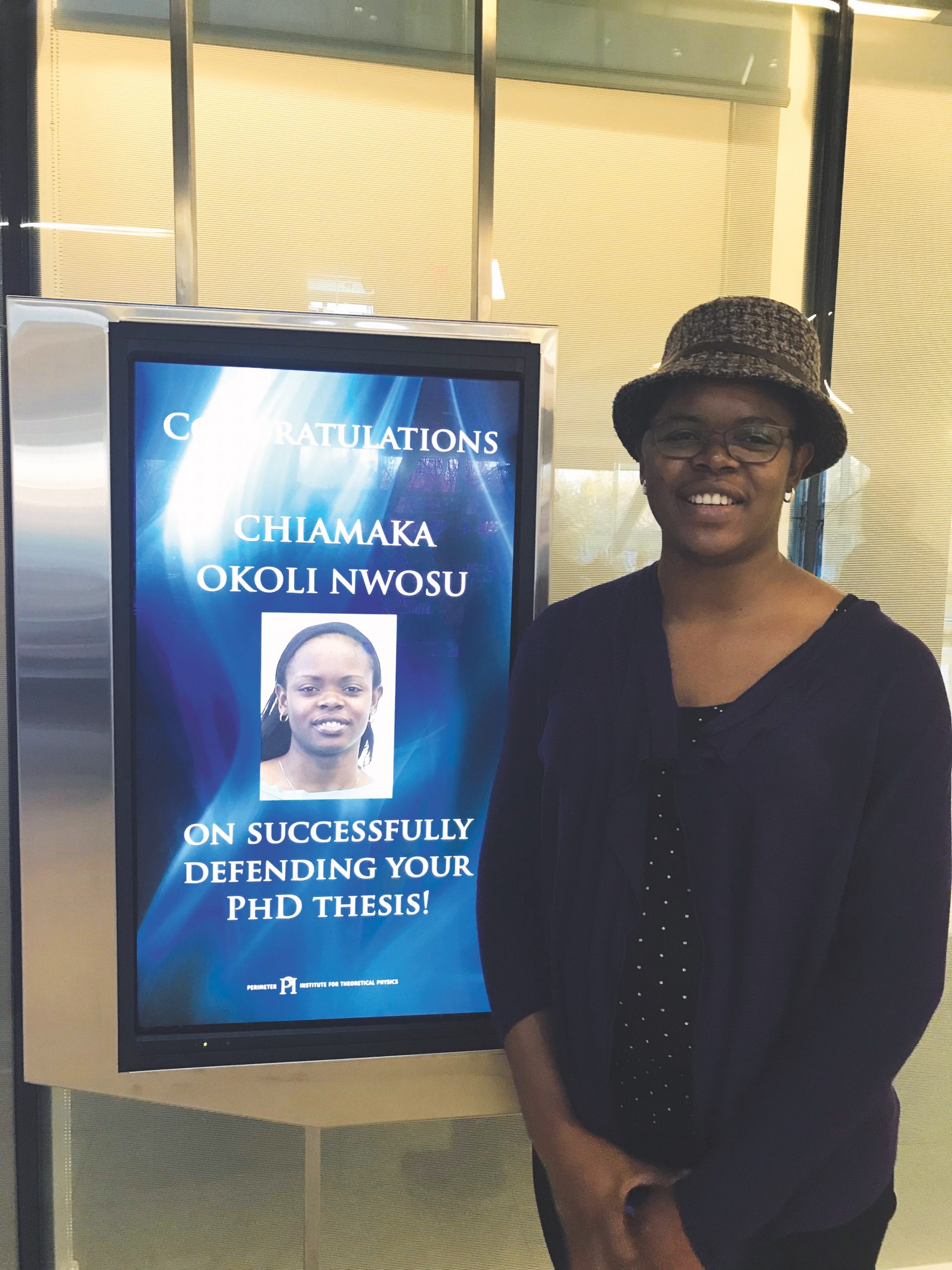

Chiamaka died over two weeks later on June 5, 2019. She was supposed to receive her PhD degree the following week, joining the esteemed alumni of Waterloo’s Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics (Perimeter even hosted Stephen Hawking for two research terms). Chiamaka was studying the nature of dark matter, which is invisible to the naked eye but is said to make up about 85 percent of the universe’s mass. She would have been one of fewer than 10 Black women to earn a PhD in particle theory in North America.

The news of Chiamaka’s death was devastating to the small community. “It makes you wonder what discoveries left this Earth when she left this Earth? What won’t be touched, what won’t be found, what will go undiscovered?” says Renee Horton, former president of the National Society of Black Physicists and an engineer at NASA.

Jami Valentine Miller, who curates the African American Women in Physics list, knows first-hand how small the club is. In 2007, Valentine Miller became the first African American woman to earn a PhD in physics from Johns Hopkins University. By the end of 2021, she estimates that the list of Black women with physics PhDs in North America will grow to more than 100. An achievement, yes, but still a relatively low number.

Even in the small group of women of colour in physics, Chiamaka stood out. When Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, an American and Barbadian theoretical physicist, first saw Chiamaka at a 2017 conference at the University of Waterloo, she immediately wanted to know who she was. Chiamaka was heavily pregnant, only a few weeks from her due date, and presenting her academic research. “To see a pregnant Black woman in a physics space is so unusual that I was like, ‘That’s going to be someone that I have to know who she is so I can keep up with what she’s going to do in life,’” says Prescod-Weinstein.

Motherhood is an additional barrier for women in the male-dominated field. Samar Safi-Harb, the lead for equity, diversity and community at the University of Manitoba’s faculty of science, says that “the [work] environment and family/career balance issues are really big.”

Chiamaka seemed to take the challenge in stride. In the acknowledgments of her thesis, she thanked her young son for motivating her to pursue her career. “Even though you are [too] little to understand this, I appreciate you, my little boy,” she wrote.

Her other life motivation was her faith — the assurance of things hoped for and, most importantly, the conviction of things not seen. Despite Chiamaka’s exceptional life, her story is familiar to women of colour. It addresses the pressure felt by those who have excelled in spaces where they are the sole representatives of their racial and gender identity.

Chiamaka Blessing Nwosu’s life began in 1987, in Bauchi, a state in northern Nigeria that is home to over 50 ethnic groups, including the Hausa, Fulani, Kanuri and Igbo, of which Chiamaka’s family is a part. Many of the groups are Muslim, but Igbos are mainly Christian. In an interview with a Nigerian newspaper, Wakilin Tahiri, chief historian of the state, says that “Bauchi was regarded as a land of unity in diversity because of its combination of so many ethnic groups all living in the same place.”

Despite this perceived unity, long-simmering religious and ethnic tensions were at play. In 1966, Igbos living in northern cities were the target of attacks and massacres following two military coups. As violence heightened, close to a million Igbos fled to southeastern states. Then the Igbos announced their secession from Nigeria to form Biafra in 1967. For the next three years, a civil war separated Nigeria’s Igbo, Yoruba and Hausa populations, resulting in an estimated 100,000 casualties and between 500,000 and two million deaths from starvation.

After the war, attempts to rebuild the country took off. In a speech on Jan. 15, 1970, General Yakubu Gowon, Nigeria’s leader at the time, guaranteed the right of every Nigerian to reside and work wherever they chose “as equal citizens of one united country.” Chiamaka’s father, Sylvester Nwosu, moved his young family from Biafra’s capital, Enugu, to Bauchi, a booming economic centre. He started a transportation business, which grew into a lucrative fleet of buses that still serve travellers across the country.

“It makes you wonder what discoveries left this Earth when she left this Earth? What won’t be touched, what won’t be found, what will go undiscovered?”

Both Sylvester and his wife, Louisa, a primary school teacher, loved education and took pride in their children’s schooling. Chiamaka was the fifth of seven children. She and her two sisters attended boarding school at the Federal Government Girls College in Bauchi. Secondary schools like Chiamaka’s were known as “unity schools,” where students from all parts of the country came together to model cultural, religious and ethnic integration, which was essential after the civil war.

Friends say that Chiamaka’s time as a student in northern Nigeria is what made her a true Nigerian, embodying the best parts of the country, such as resiliency and unity. Her family spoke Hausa, the predominant language of the state, and even though they were Igbo and Catholic, they never saw themselves as different.

But in the early 2000s, ethnic violence in Nigeria began to escalate again; cities were rocked by riots and set on fire. In Bauchi, news reports said that fringe groups had given Christians an ultimatum to leave the state. Reminiscent of a similar exodus only four decades earlier, non-Muslim Nigerians, including the Nwosus, fled to the southeast. “We didn’t want to be victims of violence,” says Benjamin, Chiamaka’s younger brother.

In 2004, the family moved to Awka Etiti. The town is only a few hours from one of the country’s most prominent post-secondary schools, the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN). With her stellar academic record, Chiamaka was admitted into the university’s physics program a year later.

For many students, including Chiamaka, physics wasn’t their first choice. Often they wanted to study medicine or engineering but ended up in physics because popular courses were at capacity. Many students were discouraged by the government’s failed promises to support science and technology. “If you are studying physics in Nigeria, it’s like you’re studying nothing…. You don’t have prospects. ‘Where will you work?’ is the first question your parents will ask,” says Nonso Enwelum, Chiamaka’s classmate, who is now a physics lecturer at UNN.

Chiamaka considered abandoning her major for courses in medicine. But after seeing her pure talent and dedication, a professor encouraged her to continue with the program. “I told her that physics would give her even better opportunities than medicine,” says her former professor Daniel Obiora. He believed that with a degree in physics, she would contribute to, or even pioneer, research that could change the world.

But success did not come easily. Limited funding marred the university. Students would sometimes rush to classrooms teeming with over 500 people, despite being built to fit only 60. Those who didn’t get a seat watched lectures by crowding outside the classroom door and windows.

Despite these limitations, Chiamaka excelled. She topped her class, earning the admiration of her peers and teachers, as well as accolades and scholarships from both public and private institutions. “She was intelligent and ready to work,” says Obiora. “She loved challenges.”

I met Chiamaka’s widower, Felix, on a snowy Saturday morning in January 2020. As I walked to the front door of his apartment building, I sent him a text announcing my arrival. A few minutes later, a man in a red polo shirt opened the door. Attached firmly to his hip was a toddler who looks exactly like Chiamaka.

Inside, little Munachi lobbied his father to feed and play with him. Looming over them on the wall was a framed picture of Felix and Chiamaka. In the image, he’s wearing a black dinner jacket and she’s in a green skirt and blouse, with a green gele or headscarf. She stands slightly taller than him, and they affectionately lean their heads together.

Felix lifted his son onto his lap and began to tell me about the 10 years he had known and loved Chiamaka.

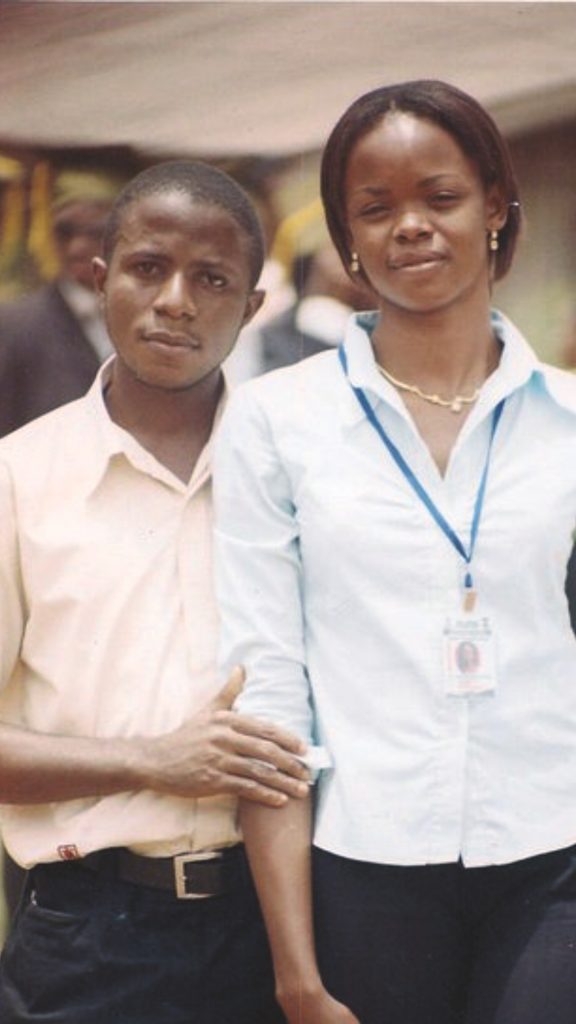

She was in her third year of university when they met in 2008. She was in line at the bank when Felix walked in to make a withdrawal. He was familiar with the staff and made a point to laugh and talk with acquaintances, while inadvertently holding up the line. As Felix left the bank, he and Chiamaka found themselves reaching for the exit at the same time.

When he saw her waiting for a motorbike taxi outside the bank, Felix offered Chiamaka a ride to school. She declined because she didn’t know him. “I said, ‘Yes, I’m a stranger, but I think you heard me talking with someone [at the bank]. So if I’m that bad or if anything should happen, those people will testify,’” says Felix.

She relented, and that ride signalled the beginning of their courtship, which was hard won by Felix. He was curious about this woman, whom he describes as decisive and principled — someone who insisted on doing things her way. “She was so focused and determined that she could not compromise her academics for anything,” says Felix.

Chiamaka liked to go on drives with Felix. When it was cool out, he would take her to a local stadium where they would sit and talk. Felix told Chiamaka about losing his father in his mid-20s and caring for his mother. Chiamaka talked openly about her upbringing and her close relationship with her father. Felix became a good friend and then more. According to Chiamaka’s friend Felicia Ntong, “love was an understatement” for what Chiamaka felt for Felix.

More on Broadview:

- How this interfaith program helps new Canadians thrive

- Inside the scramble to find culturally competent care for elderly immigrants

- Foreign workers face dilemma in coming to Canada

The couple married in 2009 at a Catholic church in Nsukka. Chiamaka was 21, and Felix was 35. A little over a year later, after graduating as the best overall student from her university, Chiamaka packed her bags and flew to Trieste, Italy, to study at the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics. “I saw the passion she had for science and that she really wanted to discover the world around her, and I gave her my full support,” says Felix, who remained in Nigeria.

In Trieste, Chiamaka was one of 52 students from all over the world in the one-year program, which is known to be difficult to get into and difficult to complete. Chiamaka studied how fast galaxies move, and how the accuracy of these measurements can affect our understanding of the Earth in relation to the universe. According to Ravi Sheth, her adviser at the institute, Chiamaka quickly became one of the top students, even teaching herself Python, a coding language, in addition to the material she was learning. “It was all new to her, and it was super impressive what she was able to do,” says Sheth.

While in Italy, Chiamaka joked with friends about not being able to follow Catholic masses because they were in Italian. But she still went. Her faith was an important part of her upbringing in Nigeria. Her brother Benjamin says that their faith was the family’s bedrock. “We don’t miss Sunday mass,” he says.

That dedication continued for Chiamaka. In the same way she understood how dark matter’s invisible force kept the galaxies intact, she surrendered her life to God, calling God the author and finisher of her faith. “I am only a pencil in Your hands,” she wrote in her PhD thesis.

In the 1970s, Americans Vera Rubin and Kent Ford confirmed the existence of dark matter. Decades earlier, theories about the unidentifiable mass that held the universe together were floated, but it was Rubin and Ford who confirmed that galaxies “must have significant mass located beyond the optical image.” During her life, Rubin was called a “guiding light” by female astronomers who followed in her footsteps.

Rubin talked openly about her experiences navigating the overwhelmingly male club of astronomy. During her time at Cornell University, her department chair called her into his office and complimented her thesis. According to Rubin, he said the work should be presented at the American Astronomical Society, but suggested that since Rubin was expecting a baby and was not a member of the society, he could present the work for her — in his own name. Rubin refused and ultimately presented the work herself. In her article “An Interesting Voyage,” Rubin wrote, “Women generally required more luck and perseverance than men did. It helped to have supportive parents and a supportive husband.”

Chiamaka was open about having both. But being a woman of colour and an African woman in a foreign country came with its own unique set of expectations. Knowing that she was part of a small group of Black women in the field weighed heavily on her at times. In Nigeria, the concept of race was virtually non-existent because most of the population is Black. Nigerians are divided along ethnic and religious lines, not racial ones. Chiamaka’s achievements at UNN were not viewed within the context of the colour of her skin or her country of origin. In North America, it was different.

“This is something that she was very aware of, and I think this put some pressure on her,” says Niayesh Afshordi, one of Chiamaka’s PhD advisers at the University of Waterloo.

The pressure seemed even more heightened after Chiamaka’s first aneurysm, and she wanted a rest. She mentioned to Afshordi that she was considering not working in academia as a physicist after her graduation. “It was too much [of a burden] basically for her to take representing all the African women,” he says.

When Chiamaka arrived in Waterloo in 2012 (Felix joined her in 2015) to begin her master’s and eventually her PhD, she built on Rubin’s work. She looked into the characteristics of clusters of dark matter, their structure and how they interacted with each other. “Her work was very important in terms of understanding what dark matter could be,” says Afshordi.

While dark matter is said to hold the universe together, there is still so much to learn. “Most of the matter in the universe is in fact dark matter,” explains Afshordi. “[Dark matter] is stuff that we know has gravity, but we can’t see it or we haven’t managed to detect it in any direct way. There is a mathematical theory for how dark matter should evolve or should move in the universe, and it’s basically through its gravity. So what Chiamaka did for her thesis was trying to model how structures made out of dark matter behave.”

In December 2018, Chiamaka successfully defended her doctoral thesis. In a photo posted on Afshordi’s website, she stands in front of a blank chalkboard, a projector beaming the title of her thesis, “Dark Matter and Neutrinos in the Foggy Universe.” Chiamaka’s smile is wide, but her eyes look tired.

Ten months before, on Valentine’s Day, Chiamaka experienced a sharp, severe headache after working on an academic presentation. She was at home with Munachi, who was six months old, while Felix was visiting family in Nigeria. She had been having these headaches for months. This time, perhaps because she was alone, she dialled 911.

“Hello, I just started having this strong headache,” she said to the dispatcher, who prodded her for details. As she was talking, Chiamaka began to lose feeling in her left arm and leg. She relayed this to the dispatcher, who immediately asked for her address. Two minutes later, the flashing red and white lights outside her apartment window signalled the arrival of paramedics. With her left side paralyzed, she somehow managed to crawl to the front door and let the paramedics in. Shortly after, she began vomiting and lost consciousness.

Two weeks later, Chiamaka woke up in the ICU of Hamilton General Hospital, about an hour from Waterloo. She had suffered a fusiform aneurysm, caused by a tear in one of her brain’s major blood vessels. To save her life, Chiamaka had been immediately wheeled into surgery, where a piece of her skull was removed to relieve pressure in her brain. She subsequently underwent a 12-hour operation to repair the ruptured blood vessel.

Like everything Chiamaka did, her recovery from the aneurysm was exceptional. After a few days, she responded to verbal cues, and as soon as she was able to communicate, she asked for her son. “It was truly a miracle. I don’t really use the word ‘miracle’ a lot. I don’t know if I believe in miracles, but it was a miraculous recovery,” says Dr. Sunjay Sharma, who treated Chiamaka. Still, it would take over a year for the swelling to go down enough for surgeons to replace the bone flap.

Being a woman of colour and an African woman in a foreign country came with its own unique set of expectations. Knowing that she was part of a small group of Black women in the field weighed heavily on her at times.

The aneurysm had come as a shock to everyone. As far as they knew, she was young and healthy — except for the severe headaches, for which she had sought help from her family doctor many times. Brain aneurysms are hard to detect before they rupture and are usually found incidentally through tests for other conditions, according to the Brain Aneurysm Foundation. Misdiagnosis or delays in diagnosis of a ruptured aneurysm occur in up to a quarter of patients. “The problem with headaches is that everyone gets headaches,” says Sharma. “And [with aneurysms], you don’t know you have it till you have a bleed.”

Despite the harrowing incident, Chiamaka was thankful to be alive — half of patients who experience a ruptured aneurysm do not survive. She began raising money for the Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation because she was “too grateful to remain silent.” She also started looking for jobs in data science in Ontario with the hope that her family could finally put down roots after she completed her doctorate.

When Felix arrived at Grand River Hospital that day in May 2019, he asked staff to call Dr. Sharma in Hamilton. He had treated Chiamaka before, and Felix trusted his opinion. Sharma asked for Chiamaka to be transported to Hamilton. “I think we, at that point, had a clear understanding that this would not be like the last time,” says Sharma.

Felix sat in the waiting room in Hamilton for four and a half hours until Sharma came out of surgery to give him an update. Sharma told Felix that they had managed to stabilize Chiamaka, but too much damage had already been done. If she survived, she would most likely remain in a vegetative state. Felix broke down, sobs wracking his chest.

Over the next couple of weeks, Chiamaka remained on life support. Her friends and family held her in prayer. Despite her prognosis, Felix clung to the possibility that Chiamaka would wake up, just like she had before. But the doctors had said that having two blood vessels fail in less than two years was very unusual. Chiamaka was tested for underlying illnesses and diseases, like West Nile, but everything came back negative. The doctors reasoned that she likely suffered from an unknown blood vessel abnormality.

On the day Chiamaka died, many mourned the loss of a bright physicist, some mourned the loss of a friend or family member, while others mourned for her husband and young son. Felix mourned for all of these reasons, but especially for Chiamaka and all the life she did not get to live.

Chiamaka’s friends and family can hardly explain her death, and when they try, they reach for a refrain that Chiamaka herself might have invoked: that God knows best. For Felix, this phrase is an expression of hope amid tragedy. And for him, Munachi is the embodiment of that hope.

I once asked Felix why he was open to speaking about Chiamaka so soon after her passing. Felix said that their son was why. “Even if I’m not alive to tell the story, at least it should be somewhere for him to learn more about [his] mom.”

Their son will eventually know his mother as a scholar and a trailblazer in her field. He will also know that she was a woman of faith.

When Ravi Sheth sent me Chiamaka’s thesis paper from her time at Trieste, he pointed to the acknowledgments, saying, “While it’s not something we discussed, the final sentence…is especially true to her character.” I scrolled through the paper to read: “Finally, To [God] who knoweth all things, who am I without you? mere dust!!!!”

***

Ashley Okwuosa is a writer in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s Oct/Nov 2021 issue with the title “Death of a rising star.“

A truly inspiring & exceptional woman.

Thank you for documenting this, Ashley.

This story on the death of a rising star engaged me as it would engage anybody who in a true intellectual, person of faith or colour, or indeed anyone concerned about the progress of the humankind and society as a whole, in social justice, equity and mutual respect.

Both the author and Broadview (as the publishers) have done very well to bring this inspirational writing to people like me. They deserve some prize of real high value; and I wish I had the means to do so by myself. However, as it is, I know that both NATURE and the very Almighty God whom we can all feel in our inmost beings will know how to reward them otherwise, even if nobody else does.

So, to them we say, well done; and God bless you, plentifully!

Thanks Ashley for this glowing ode to a sister I loved so much. Sadly I still can’t find myself writing about her because words fail me each time I try. When she passed I was so numb and dumb for months. I couldn’t cry because tears wasn’t strong enough to carry my heartache.

Seeing this tribute brought back some semblance of smiles along with the long memories of our time in Bauchi when Chiamaka was forced to start school too early because at the kindergarten where she was being cared for she was starting to genuflect when Muslim prayers called.(The daycare home was run by a Muslim) Thus she was yanked off to formal school before the required age.

Adieu, rising star and thank you for contributing your quota to Science and continuing to inspire the living.