Last December, I bought an AncestryDNA kit. It would turn out to be the most life-altering decision I’ve ever made. I was adopted at birth and found my biological mother over nine years ago when the adoption laws in Ontario changed and I received my original birth record in the mail. Our first and only conversation was polite but strained. My biological mother made it clear she didn’t want to pursue a relationship and refused to tell me who my father is. Her reluctance to share the other half of my genetic makeup nagged me for nearly a decade. I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was something medical that I needed to know. I had no idea then how right I was.

On my 45th birthday last December, I mailed my biological mother a letter, asking her again who my father is. “I know I represent a traumatic part of your life. I feel badly about that. And yet I also feel that you are controlling information that I have a right to,” I wrote. “Your secret not only robs people [of] the right to make their own decisions regarding their relationships with me but it may put my health and my children’s health at risk. I would like to know who my biological father is.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

There was no response. A few weeks later, I spit in the tube that came with the AncestryDNA kit expecting to discover my cultural heritage. Instead, I inadvertently unravelled a closely guarded secret decades in the keeping. Nothing’s been the same since.

Since 2007, when 23andMe launched the first direct-to-consumer DNA kit, over 26 million people have offered their genetic code for analysis, according to MIT Technology Review. For adoptees like me, the accessibility of DNA testing is a cataclysmic game changer. While the commercial tests are relatively new, stories of the impact on adoptees searching to fill in missing pieces of their identity are piling up. What is unique about my story is how it so thoroughly encapsulates the extreme ends of the experience, at once embodying the most beautiful and devastating consequences of DNA testing and adoption reunion.

On a frigid, run-of-the-mill Wednesday in January, I was writing my Sunday sermon when I received an email from AncestryDNA saying that my test results were in. I sat cross-legged on my bed, scrolling on my laptop, unsurprised to learn that I’m over 80 percent English, Irish and Scottish. Then, I noticed the matches section.

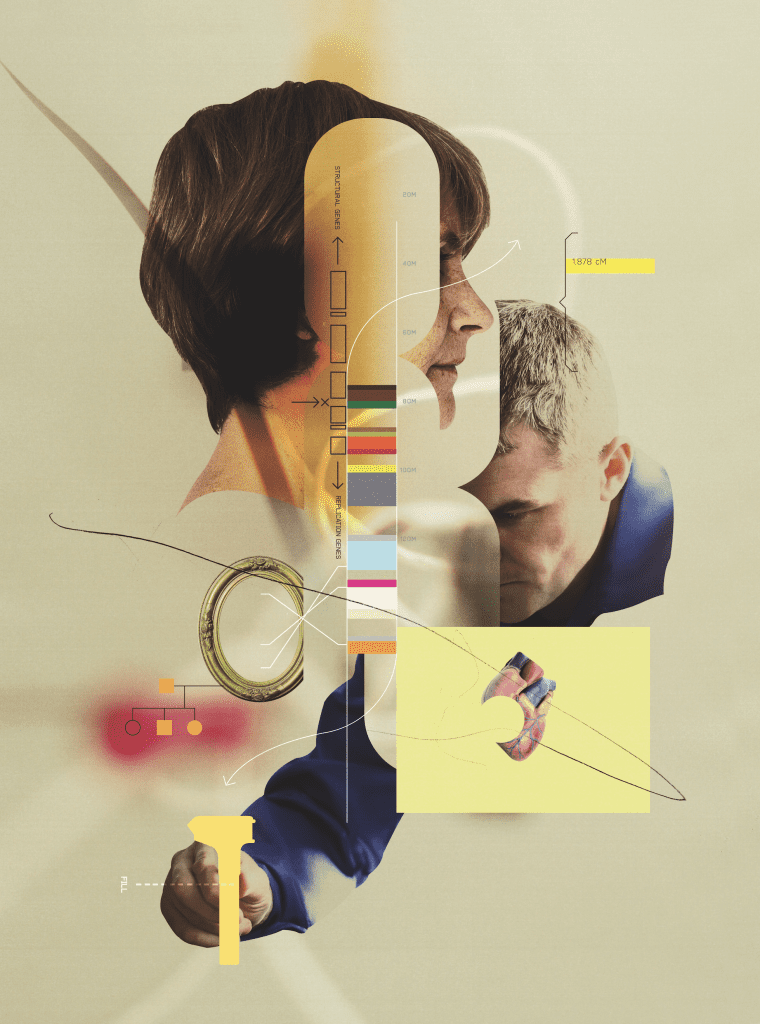

I gaped. The name “Lorne Neville” came up under the category “Close Family.” Ancestry notes that the amount of DNA we share is 1,878 centimorgans (a unit to measure the similarity of DNA) across 61 DNA segments (locations in the genome). What does that mean? I dug into the explanation. Between 1,450 and 2,050 shared centimorgans can indicate a grandparent, aunt, uncle or — could it be? — a half-sibling.

I hovered over the surname, recognizing it — for reasons that are complicated. As you’ll come to understand, I have legitimate reason to fear that I or my loved ones could be physically harmed if I divulge all of the secrets that later came to light. Suffice to say, the rest of the day, I alternated between staring at the name on the screen and googling the accuracy of AncestryDNA results, the ins and outs of chromosomes and the variables of interpretation.

More on Broadview: Family estrangement a ‘silent epidemic’

Knowing the geographic area in which the Neville family lives — a small town near the one where I grew up — I quickly found the phone number of the automotive garage Lorne owns. “You gave your mother nearly a decade to tell you the truth of who you are,” I assured myself when I hesitated to pick up the phone. “Don’t overthink it.” I began to dial. There was no answer. I left a polite, brief message.

As I was driving to a church retreat the next day, Lorne called. He thought I wanted an oil change. I pulled onto the side of the highway, shaking so hard I spilled my coffee, burning my hand.

“Are you Lorne Neville and did you submit your DNA to Ancestry?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, his voice arching.

“Have you been on the website lately to receive your notifications?”

“No.”

“You should check it out. I don’t know the best way to say this, but I’m calling because we matched.”

“What?!”

In the 10 minutes we spoke, I stammered across a lot of ground: Could we be siblings? Maybe the DNA is wrong. No, this isn’t a crank call.

“I’ll get to the bottom of this, and I promise I’ll get back to you,” Lorne vowed before hanging up.

When I met my brother, what I lost was literally standing in front of me. I grieved for the years we could have spent together — an immediately knowable, gaping chasm. There was also guilt.

The next day, we arranged to meet at a modest diner a half-hour drive for both of us. As I waited inside, I started to sweat, my arms sticking to the back of the duct-taped, vinyl booth. Lorne was late. Maybe he wouldn’t show? I bolted to the rickety bathroom, splashed cold water on my face and hid behind the corner so that I could watch him walk in from enough of a distance that I could make a break for the door if I chickened out. And then there he was, craning for me. Broad shoulders. Dark hair. Tanned. Later, I would learn he is just over a year older than I am. I took a deep breath and walked over.

“Hi. I’m Trish,” I said confidently, trying to sound more together than I felt. While I nervously recounted all the events that led to our meeting, he catalogued my features, his lips slacking in shock. I stared at my hands, avoiding his gaze, giving him the privacy to gawk, sneaking my own furtive glances. We have the same eyes. Our mannerisms are similar. We ordered dinner. He too prefers mashed potatoes over fries. He’s personable, funny, smart. Kindred?

I reiterated this isn’t a hoax and slid my birth certificate and all of the other information I’d gathered over the years across the table. He barely looked at it. He didn’t need to. His eyes never wavered from mine.

“I think you’re my sister,” he said calmly as we wound up our meeting. “I think we have the same father. I will find out for sure, and I promise I’ll be in touch again.” Pause. “Trish,” he said in the slow, direct, warm way I’ve since come to love. “Is this going to be good?”

“I think so. I hope so,” I replied, hugging him as we left.

The next day, he called. “I have the answers you need,” he said. “I’m old-fashioned. I don’t want to tell you over the phone. When can you come to the garage?”

Lorne’s garage, Neville and Son Pit Stop, is a pristine automotive business with three large bays and a phone that rings off the hook. In the reception room, Lorne flipped the sign in the front window to “Closed” and handed me a greeting card, obviously anxious. I opened it and read the signature line first: “Your brother, Lorne.” I leaned over the desk, my hand over my mouth, shocked that I finally would know the truth. I didn’t notice Lorne behind me until his big bear arms were wrapped around me, tears welling up. “I’m so sorry. I didn’t know until now,” he cried.

Pressed together and weeping, neither of us could have imagined the challenging dynamics that would storm around our reunion or how finding each other would impact us and everyone we love.

In the weeks that followed, waves of revelations washed over me: the shocking circumstances around my conception; my family tree; the length to which my biological mother and some other family members would go to try to keep the secret of my existence buried; the identity of my biological father; and, just as disturbing, that I was too late to meet him. My father died at just 37, after having 12 heart attacks. When Lorne told me he also nearly died having two heart attacks before turning 45, I had to sit down. It was all too much.

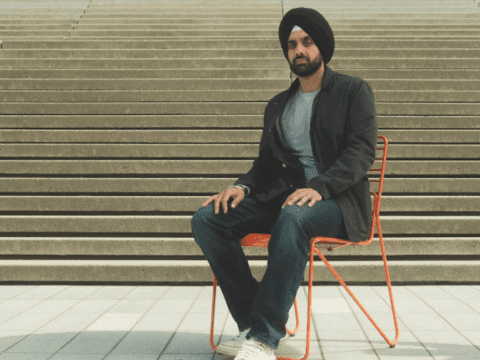

I reached out to a Toronto-based therapist knowledgeable in adoption reunion processes and an adoptee himself. He helped me wade through the flood of emotion. “I knew there was something,” I told him over the phone. “I go from having empathy for my birth mother and all the pain she experienced having been sent away at 16 to give birth alone, to being deeply angry that she knew about the genetic heart issues and didn’t tell me. How can keeping a secret matter more than someone’s life?” I railed, making a mental note to get myself and my sons tested. “And all of these family secrets coming out. I never meant for this to happen.”

“You were seeking information about yourself you have the right to,” the therapist assured me. “Adoption reunions aren’t a sprint. They’re a marathon.”

That would prove to be an understatement. When I met my brother, what I lost was literally standing in front of me. I grieved for the years we could have spent together — an immediately knowable, gaping chasm. There was also guilt. I was raised in a comfortable middle-class home, handed every opportunity, while Lorne created his own after our father, who worked as a mechanical engineer, died when Lorne was 11 years old. Lorne slogged through multiple jobs and slept just four hours a night for over a decade to break the ground his dream business is built on. Though he is equally ambitious, determined and successful, I had an easier path. And then there’s sadness around the relationships I increasingly doubt I’ll ever have with my other siblings who turned up as a result of the process. To date, none have acknowledged me.

_________________________________________________________________________

The secret of my existence is coming to light in a close-knit, rural community. Shame is especially hard to spring from in places where everyone knows your business. A different day, I was visiting Lorne at the garage when my biological uncle walked in. He did a double take when he saw me because I look like my biological family. I tried to act nonchalantly and extract myself from the awkward conversation. He didn’t yet know who I am, and I didn’t think it was my place to tell him.

After my uncle left, Lorne called a family member, asking for a meeting to work out how to break the news of us finding each other and begin to heal the family relationships. The conversation got heated. Lorne stormed outside. “Trish isn’t a dog that you can just leave out on the step!” I overheard him blast into the phone. Acknowledging me has cost him some of his relatives who blame him for not leaving things as they are.

During another visit with Lorne, I saw the verbal abuse turn physical. I had recently posted a picture of Lorne and me at a baseball game on my personal Facebook page. A member of our biological family stormed into Lorne’s garage in a fit of rage, grabbed him by the shirt and threatened to “finish” him. Lorne immediately tried to protect me from whatever was about to happen. “Get into the office and stay there until I tell you [that] you can come out,” he told me.

Lorne and I have drained coffee pots over conversations about the secrecy and shame swirling around my birth and whether or not our relationship should be swept up in it. This violent incident — an attempt to erase the pieces of me I’ve finally managed to put together and to bully my relationship with Lorne into a closet — shocked and horrified us both. Are we obligated by the shame of the past to deny each other?

“I am my mother’s secret,” I once wrote. Now, I am becoming less my mother’s secret by the day and yet I’m still tied to it and I wonder to what extent I ought to be. I’ve stewed over the dilemma for months yet I always arrive at the same conclusion: being forced to deny your own existence and relationships is the definition of dehumanization. Lorne puts it more simply: “Secrets got us into this mess. I refuse to lie.”

_________________________________________________________________________

The adoption reunion process is a vulnerable time all around, laden with lifetimes of pain, secrecy, shame and denial. For adoptees, it is like being reverse-adopted, waiting to see who in your biological family will accept you and who won’t, shoring yourself up to be relinquished again.

I tried to explain the dynamics in a letter to my two teenage sons, who were puzzled in the early days of reunion by my uncharacteristic tearfulness and absent-mindedness. Three months into the reunion process, I called them down to the living room for a family meeting to read them the letter. I explained that adoptees have two identities: genetic and adoptive. “I didn’t know anything about my genetic identity. That means that I didn’t know where I came from, who I looked like, where my personality was formed, etc.…We know today that babies in the womb know their mother’s voice, even her moods. The first experience I had outside the womb was of losing my mother.”

The cultural mythology of adoption is hard to dislodge; the emotional stakes in maintaining it run high on all sides. Children adopted in the closed system, where the identities of the biological parents are kept sealed, are told through popular culture and sometimes by friends and family that their genetic self doesn’t matter. They’re led to believe they’re ungrateful or disloyal if they are curious about where they come from. Even in the open system, where adoptive and biological families have access to some information about one another, adoptees continue to be advised to be thankful for having been adopted if they “had a good life.”

Of course, I am grateful to have been raised by loving parents (which ought to be the right of every child). But my positive adoptive experience doesn’t erase the harm that accompanies not knowing my genetic identity, a harm that is well-documented academically yet remains culturally unrecognized.

Books for adopted children commonly position them as “chosen” in order to reinforce belonging. My parents used to read books like this to me, but those stories never rang entirely true. The reality is that many adoptees were first unchosen — often by mothers who faced little or no real choice as oppressive societal pressures compelled them to relinquish their babies. On the other side of the equation, while adoptive parents do choose to adopt, some wouldn’t have made the choice to if they had been able to bear children. In those instances, adoptees know full well they are a second choice.

How adoption is perceived colours the potential for reunion. Why open the door to meeting if DNA is meaningless except in a lab, if the loss of adoptees isn’t recognized and if there’s a risk of unsettling the familial status quo? In the extreme, mythologies about adoption are used to legitimize aggression against those who seek reunion and those who have decided to love them.

Conflicting notions of family compound the issues. I’ve come to believe that the adages “blood is thicker than water” and “family is what you make it” are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Both truths testify to the power of our DNA and our choices. Nature and nurture are both drivers.

Getting a glimpse of how much I’m driven by nature and how that knowledge is changing me is hard to articulate. I describe it as living for 45 years with half an identity, unconscious of how much was missing. Now, the reunion process is filling in the other half, and I can’t foresee the person I’m shaping up to be. My reformation is as painful as it is awesome.

More on Broadview: Christians should stop using God to sanctify adoption

One Sunday after church, Lorne pulled up in his orange Jeep to take me on a road trip. We drove past the farm where he grew up, circled around the garage he managed as a teenager and the road he drove his first dirt bike down. We swung by the motel and restaurants where I worked, the river I spent my summers snorkelling in, the church where I grew up. How do you catch up on 45 years? There aren’t enough hours in the day. We compared divorce stories, empathized with parental struggles and argued about who would pay the pizza bill. We wound up at my adoptive parents’ house.

“Are you sure they are going to be okay with this?” Lorne asked.

My parents were startled but predictably gracious. I’ve tried to manage the fallout for them. The week after I met Lorne, I drove to their house to reassure them that our relationship wouldn’t change. My mother hauled out a large Rubbermaid container filled with certificates, medals and other testaments of my accomplishments to highlight the opportunities I had because I was adopted. “Don’t forget about us,” she called out as I left.

“Would I even be here if I had forgotten about you?” I asked, trying to sound more empathetic than irritated.

Later, on Mother’s Day, I stood behind the pulpit at the beginning of the service and saw my mother wiping her eyes in the pew and Lorne looking verklempt beside her.

“What happened?” I asked Lorne later.

“There were just a few things I wanted to say to your parents,” he said evasively.

“Like what?” I pried.

“Like thanking them for doing such a good job of raising you,” he said.

Conflicting notions of family compound the issues. I’ve come to believe that the adages “blood is thicker than water” and “family is what you make of it” are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

I’ve never been much of a believer, at least not in destiny, or in an interventionist God. I tend to put a lot of stock in human agency. The idea of being in control is comforting. Yet, I’ve never felt so inexplicably guided. There are too many coincidences: unbeknownst to me, I wrote the letter to my mother last November on my brother’s birthday, later mailing it on mine. While he wasn’t the only member of the family to submit DNA, Lorne’s was the first to match, and he’s the only one who, so far, has been receptive to meeting. To top it off, he is not the sort to submit his DNA to an online database. He doesn’t even have a personal email address.

“I just always felt that there was something of my dad’s I was missing,” he said, explaining why he took the DNA test. “Now I know it’s you.”

Like the disconcertingly beautiful tale of symbiosis some twins tell, Lorne and I are eerily connected. Countless times we have texted each other at the same moment, sharing the same quirky thought and finishing each other’s sentences. “I just know you are out for a walk so thought I’d call,” Lorne said over the phone in the middle of the afternoon while I was spontaneously strolling through the neighbourhood.

How to account for this inexplicable intuition? Is it a fluke of wiring? Recent scientific studies speculate that our genes carry memory, influencing the way we experience life. In a study published in 2013, for example, mice who were trained to fear a specific smell passed on their aversion to their grandchildren, who dreaded the same scent, even though they had never encountered it before. Are memory and connection genetically inherited? Are my brother and I guided by the same hardware? The answers the DNA kit has provided have raised new, more sweeping questions.

_________________________________________________________________________

Cornfields border the burial ground, new shoots announcing their presence in waving, green rows. It’s Father’s Day. Lorne and I are attending the annual memorial service at the cemetery where our father is buried. Community members sit in lawn chairs in an open green space. There is a podium at the front with speakers. Two musicians and the minister are busy preparing for the service.

“Take my arm,” Lorne offers, extending his elbow. I hesitate, spotting other family members in the crowd, but Lorne is firm. “Take my arm. You are my family.”

A few eyes train on us as we unfold our camping chairs and settle in. The preacher begins to pray, and Lorne leans over to ask if I’m okay. “Fine,” I say. Likely a lie. “I just feel numb,” I confess more honestly. “I don’t know how I feel, really.”

My search for my biological father ends at his grave, which has an engraved heart and the words “Precious Memories” — none of which I have.

“You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies,” the preacher recites the 23rd psalm’s audacious vision of God as a chef, laying out a feast while enemies hover, hungry: a bittersweet image of love amid pain.

After the service, Lorne points out the gravestones of extended family as we walk through the cemetery back to the car. I need to pinch myself. I feel like I’m living someone else’s life.

Yet, here I am — in a place designed to honour life and death, a place that elicits sorrow and togetherness, a place of closure and new beginnings. With my brother. Choosing love. Choosing to exist.

***

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s January/February 2020 issue with the title “Next of kin.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.

What a shame her bio mother would want nothing to do with her. The ultimate rejection. Thankfully having her loving brother will help.

Articles like this make me very thankful to God that I grew up with my natural parents, who never divorced. Because of this I cannot put myself in this person’s shoes. I cannot put myself in her parent’s shoes either. Perhaps the biological mother has regrets or hurts she is now suffering as a past wound has now been reopened. If I were the writer, I’m sure I might want to question my natural parents’ whereabouts, but at the same time what she is doing is selfish on her part.

If she is happy maintaining the relationship with her brother, so be it. We don’t know the whole story as to why she was “given up”, there may be a very valid reason (whether you agree or not) her mother wants nothing to do with her.

Hi Gary, One of the interesting things I have been learning is that the response to adoptees varies but is shockingly consistent when it comes to the rejection “process”: denial, blame and then family pressure on other members to disassociate and ostracization of those who don’t. That’s why I wrote the story. I hope that sharing the dynamics in my case will help other adoptees in the process know what could happen. I also hope it gives pause for reflection for those in the throws of reunion and are having to confront the pain of the past. My inbox is already full of similar stories -one involving a death threat on the adoptee. There are definitely old wounds involved all around (the process has rubbed salt in my own) but I don’t think anything justifies physical assault and other forms of violence on adoptees and those who choose to love them.

I have a situation, where innocently I wanted to reconcile the past. It was thrown back with threats of lawsuits and harassment charges.

I guess we need to consider that God is control of our lives, and we need to accept our current standing and aim ahead with His love and help. We need to avoid the “what ifs” and regrets we have, and be satisfied where God has led us thus far. It reminds me of the Israelites, while in the desert, who wanted to return to Egypt, stating things were better there. That cost them their lives as well.

For Trish, I too did my DNA and discovered a 19yo nephew. He was looking for his biological dad, after his mother disappeared and his adoptive father died. My older brother is his father. We have all since connected, and my brother has met him. He looks so much like his father. Although he lives in the Midwest US and doesn’t have a passport. But we’ve shared a lot about our family and made sure he knows he’s loved.

DNA can be a both unsettling and a blessing.

A very touching and thought provoking story … thanks for having the courage to share it with us.

I have been following Trisha Elliott’s story through successive articles, and I am shocked and puzzled over her mother’s refusal to meet with her or acknowledge her. I can’t understand the reaction of some of the extended family, either. It says a lot about how toxic secrets can be! If some family members read the article, I hope they have a change of heart!

This is such a touching story. I will pray for you and your brother. God bless us all.

I have felt a piece of me was missing since a child. When I was around 10 years old, I came across some letters in an old trunk that had been written during WW2. From that letter I found out that my father has another child, born in England.

Years later, after a reunion trip to England, one of his sisters (who had also been stationed in England during WW2 and was on the trip), told him that they had someone they wanted him to meet. My father told me that he was not sure who he was going to meet–he thought it was going to be his child. It was not–the person he met was my cousin–Two of my father’s brothers were killed in WW2. This was the son of his oldest brother–who had grown up not knowing his “father” was not his biological father–his mother had never told him and was not too pleased that he had been found. My father died without me getting details of his child’s birth mother. Around that time, my aunt told my mother that my father had a daughter in England–My mother told my aunt at that time that she was not interested. My aunt said nothing to me although I saw her weekly not wanting to create waves. Some years later My mother told me this–I told her, “But I am.” I visited with my aunt and asked her for details- she told me she had met the birth mother and her family but she could not remember names–she was now in her 90’s. Off and on I have tried to look online to try to see how I could find her. She would be in her 70’s likely by now if she is still alive–I often wonder does she know that her father was a Canadian? Would she want to know she has a half sister and half brothers? How I wish I had the finances to find her–time is running out if it has not already run out. Does she look like me–are we alike?

I’d never quite understood the confusing feelings an adoptee experiences until the day I met a 79-yr-old distant cousin from a branch of my dad’s family he’d known nothing about his entire life. The woman was the aunt of a long-time friend’s husband I’d very recently learned was my 5th cousin. I reached out to take her hand and introduce myself as “Glenda’s friend”, but what came out instead was “My dad was your 4th cousin” when it hit me that, unlike my own, she was from a huge, close-knit family I knew absolutely nothing about. A feeling I deduced must be similar to that of an adult adoptee on learning he/she’s adopted. Left me off balance for weeks. In my case, I was welcomed with open arms. I can’t even imagine the rejection and physical threats you and your new-found brother were subjected to. What a sad bunch of people to be related to!

I don’t know how anyone could blame an innocent child. If this man was loved, his loved ones should love all of him and put to rest the shame of the past. I am happy for you that you’ve found your brother and formed a genuine bond… you can’t have too many good , loving people in your life. I hope the rest of your family can realize this.