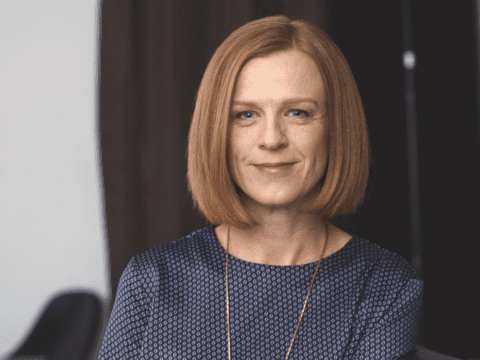

Cathy Crowe is a street nurse, homelessness activist and author in Toronto. She graduated with her nursing diploma from the Toronto General Hospital School of Nursing in 1972, and has since gone on to a high-profile career advocating for those living without housing, eventually receiving the Order of Canada in 2018. Crowe’s new book is called A Knapsack Full of Dreams: Memoirs of a Street Nurse. She spoke with Seila Rizvic about how health-care services have failed some of our most vulnerable.

Seila Rizvic: In your book, you describe a moment 20 years ago when a homeless person first coined the term “street nurse” to describe the work you were doing. What is your definition of a street nurse?

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Cathy Crowe: It’s someone who, wherever she or he is working, is really specializing in providing health care to people who are homeless. And depending on where they are and what the issues are in their community, the work can be different. It can involve outreach and providing clinics, shelters and drop-ins, or it can be more mental health-focused, or tuberculosis-focused.

I’ve worked in a lot of different settings as a street nurse, but I think at its core the work goes beyond the hands-on nursing and the clinical piece. We’re analyzing and keeping abreast of the changing nature of the conditions that are affecting people’s health and then working upstream to deal with them. So, there’s a lot of advocacy and lobbying to try to find solutions, as well.

SR: You also write that a nurse is a witness. What do you mean by that?

CC: I think nurses, no matter where they work, witness really intimate moments in people’s lives. Whether it’s in the hospital or elsewhere, people are weakened and more exposed in illness. There’s a natural trust and rapport that develops between somebody and a nurse, so you hear and see things, you’re witnessing things.

But it’s not just about seeing things. It’s also about acting on them. And recognizing trends. That’s why the street nurses’ network is so helpful; it helps us to realize there are other colleagues seeing the same health trends.

SR: Walk me through approaching someone on the street as a nurse. How does that interaction go?

CC: I’m not really doing that as much anymore. But in the past, I would have my knapsack, during heat alerts and cold alerts in particular, or if we were learning about certain new encampments of people that were in our area, we would literally go out and approach people on the street.

I find sometimes people are approached on the street too much. So it has to be relevant to the person. I used to say, “Hey, I’m Cathy. I’m the nurse at Queen West. Do you ever go in there? Anything you need? We have drop-in hours.” Just letting them know. It’s really just saying, this is who I am, this is where I’m from. If there’s anything you need, we’re here. And people kind of get to know you that way; it’s a way of building trust.

More on Broadview: Instead of retirement, two nurses battle Vancouver’s opioid crisis

SR: Can you speak a bit about the connection between housing and health outcomes?

CC: For all of us, if we think about our home, we know what it does for us. We have a medicine cupboard; we have a bed to sleep in; we can have friends over; we can be less socially isolated.

One of the biggest situations I saw first-hand was Tent City, an encampment of about 140 people in Toronto. When they got evicted, there was a huge protest, and we held press conferences. The people ultimately won a special rent supplement program, meaning their income was topped up so they could afford a regular apartment.

The City of Toronto did a research study after that and found that people’s health improved. People gained weight, people were able to reconnect with families, some people went back to school. People felt healthier.

Of course, health is also linked to poverty and other factors, but I think everything we’re doing for people who are homeless in terms of health care is just a Band-Aid if we can’t figure out the housing piece.

SR: And do you feel we’re going to figure that out? Are you hopeful?

CC: It depends on what day you ask me. I think partly I feel a bit more optimistic today because I was able to do something this morning already, which was complain to the city ombudsman about Toronto’s lack of shelter beds.

But overall, the picture is bleak. We’re in a really dire situation nationally, but in the big cities in particular.

I feel very depressed right now about the future of leadership on this issue.

SR: In what sense?

CC: The sheer volume of homeless people, the crowding in shelters, the lack of space, the municipalities’ retraction from providing emergency services, the lack of activism, the fact that researchers and big agencies receive money from senior levels of government so they’re very silenced.

What front-line workers are seeing is traumatizing to them. It feels like there’s a cold-heartedness at the political level. And in Toronto, certainly, the downsizing of city council means it’s much, much harder to get a compassionate response from city councillors.

SR: Has all this taken a toll on you personally?

CC: There was one period where I had to step down and take a medical leave from work because the grief was too much. My dad had also died, and a close patient of mine had died. I was really being triggered by things, too.

Over the years, I’ve tried to develop a lot of coping skills. I exercise a lot. I spend one or two days looking after my grandchildren, which is like a massive antidote to any problems. I tried tai chi this summer. Writing really helps a lot.

But I’m very much affected still, to this day. I feel very depressed right now about the future of leadership on this issue.

SR: Is there something about this issue that you feel most people don’t understand that you wish they did understand, something that would help connect the dots?

CC: I wish they understood that housing really is the answer. And it has to be deeply affordable housing, social housing. I don’t think most people know that it was after the Second World War that we developed a national housing program. We once did this, and when we did it, we built 20,000 units a year. [Political leaders] have to be brave; they have to be strong. Right now, it’s a weak time for political action.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length. It first appeared in Broadview‘s December 2019 issue with the title “Housing as health care.”

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.