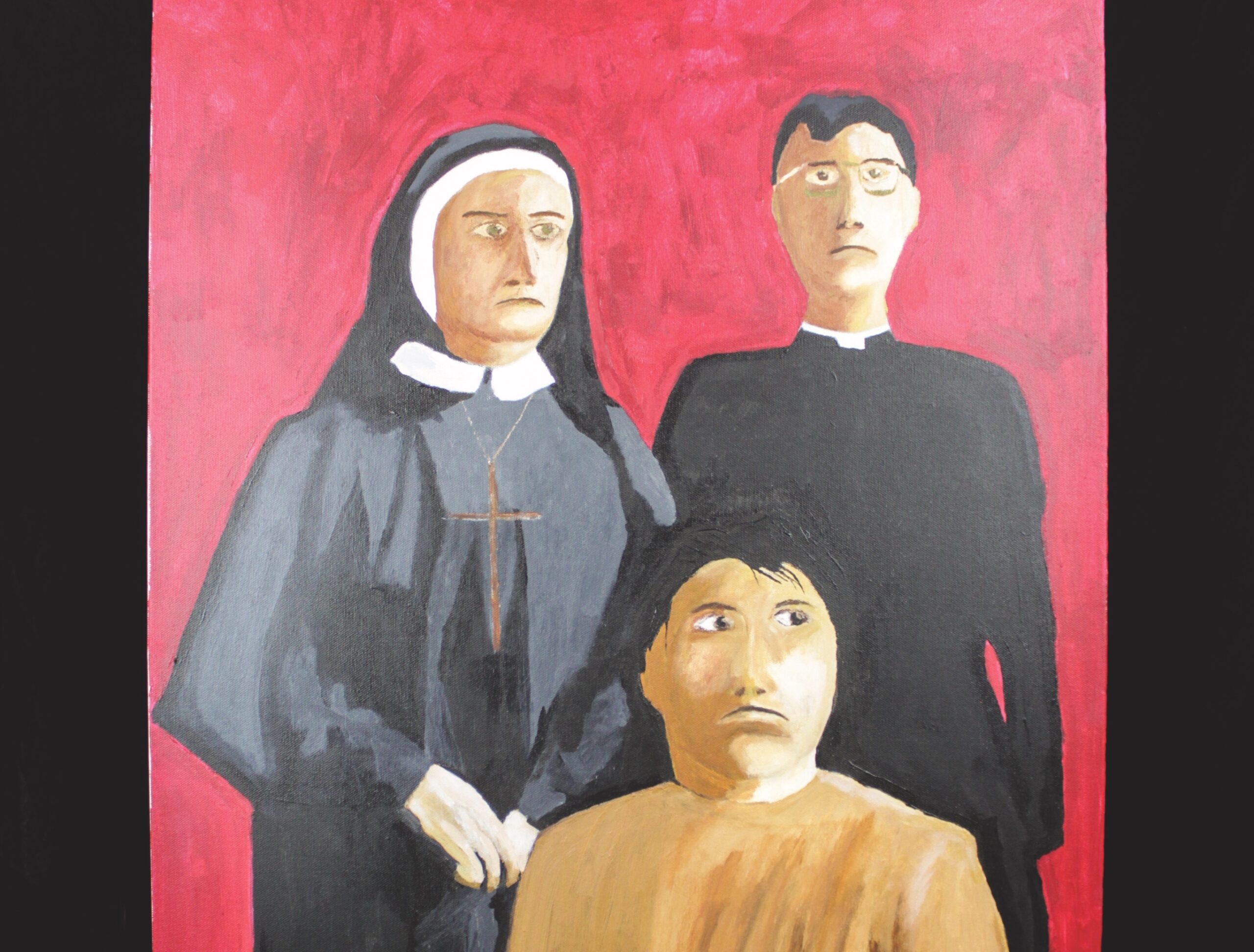

Last year, I learned from the post-adoption agency that both my birth parents are dead. Also last year, I received a grant from the British Columbia Arts Council for a two-week artist residency. I had time to process my emotions directly on canvas. All of these paintings are about my father and for my father. They are letters I write to him.

I wonder if he thought about me as often as I have come to concern myself with the life that he once lived as an Anishinaabe man and residential school survivor. Though I never knew his voice, his fears or the warmth of his fatherly embrace, he was a person just around the next corner, barely out of my line of sight. Institutional walls kept us apart for my entire life, and now that he lives among the stars across the river, I find myself searching every poem I have written, every picture I’ve painted and every dream I have had, looking for him.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

More on Broadview:

- How to ensure Indigenous tourism experiences support the right communities

- Residential school survivor wants Catholic Church to pay millions originally promised

- I’ve stepped inside Kamloops Indian Residential School. This is what it’s like

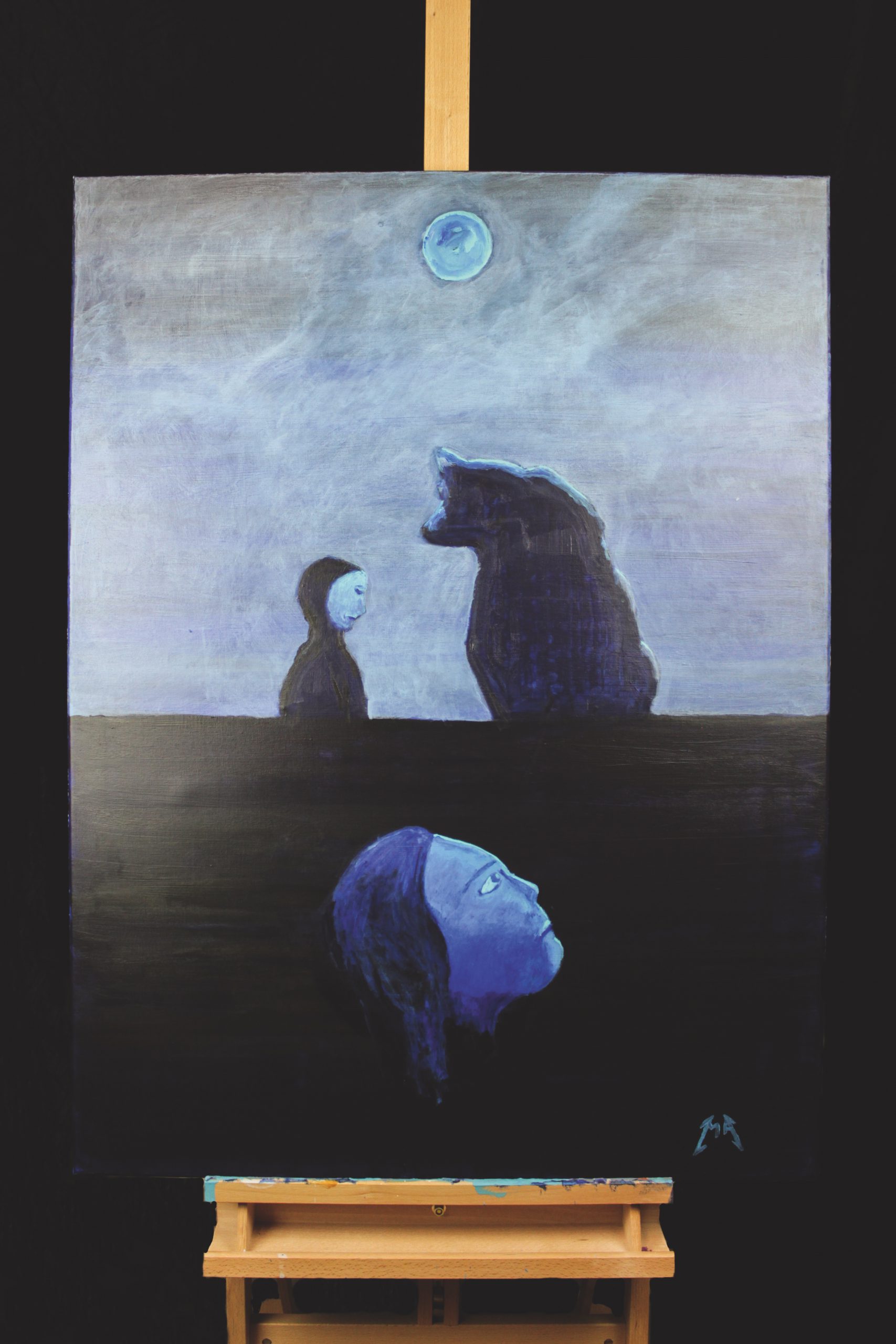

In these pictures, I have brushed his image into clarity the way an anthropologist might reveal a long-buried ancient artifact, with a delicate and breathless touch.

I’m a product of a time when my father was made to feel less than human, a time when the glimmering birch trees absorbed every distraught tear that fell to the earth. His disappearance cratered me without my even recognizing the damage at first.

Father, here and now, I see you the way that our ancestors want me to as I gently miss a man I never knew. With a sun beginning a slow descent, lifting Grandmother Moon, I understand that we have always existed within a circle, and in this place we cannot be separated any further. The same birch trees that kept the lashing of the winds at bay in the dark as best they could now help tell your story. The wisdom of our land manifests itself in my visions of you. I become a part of the landscape much as you are. As the trees speak of your laugh and your love, they too bend in the storms, promising that they will never fully break.

***

Mike Alexander is a painter and writer. He lives in Kamloops, B.C.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2021 issue with the title “A boy and his father.”

Emotional support or assistance for those who are affected by the residential school system can be found at Indian Residential School Survivors Society toll-free 1 (800) 721-0066 or 24-hr Crisis Line 1 (866) 925-4419.