Growing up in Winnipeg, I visited the Manitoba Museum several times a year. The museum memorialized the past by displaying the glassed-off artifacts of a long-lost people, obtained through the theft of cultural objects. The adjacent plaques offered a narrative created by curators with questionable intentions. When I think about it now, these exhibits were designed to hide the catastrophic experience of the colonialism that shaped Manitoba. I never felt a connection to my identity or sense of pride walking through that museum, despite the whole thing being built on my land, telling the unique story of my territory.

But exploring Indigenous cultures can transcend mannequins garbed in stolen property. Indigenous people are alive, and our cultures are thriving. As Canadians emerge from the pandemic and safe travel becomes possible again, they may wish to look closer to home. Across Canada, there are hundreds of Indigenous-led tourism experiences that are interactive and immersive, that place Indigenous culture in the present tense to promote a better understanding of Indigenous people.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

More on Broadview:

- Ottawa churches build serene space as part of reconciliation project

- Young Mi’kmaw activist raised $7,000 for Indigenous lobster fishers

- Land-based camp connects church and Indigenous communities

For example, you can learn how to make a drum or to perform a traditional friendship dance. Enjoy a Métis jig. Take a guided tour through a garden to learn about native species and medicines that are used for ceremony and healing. Try your hand at ice fishing or don a pair of snowshoes to experience winter trails. Take a paddle on a river used by our ancestors for millennia. Whatever you choose, take the time to listen, to research, and to contemplate our uniqueness.

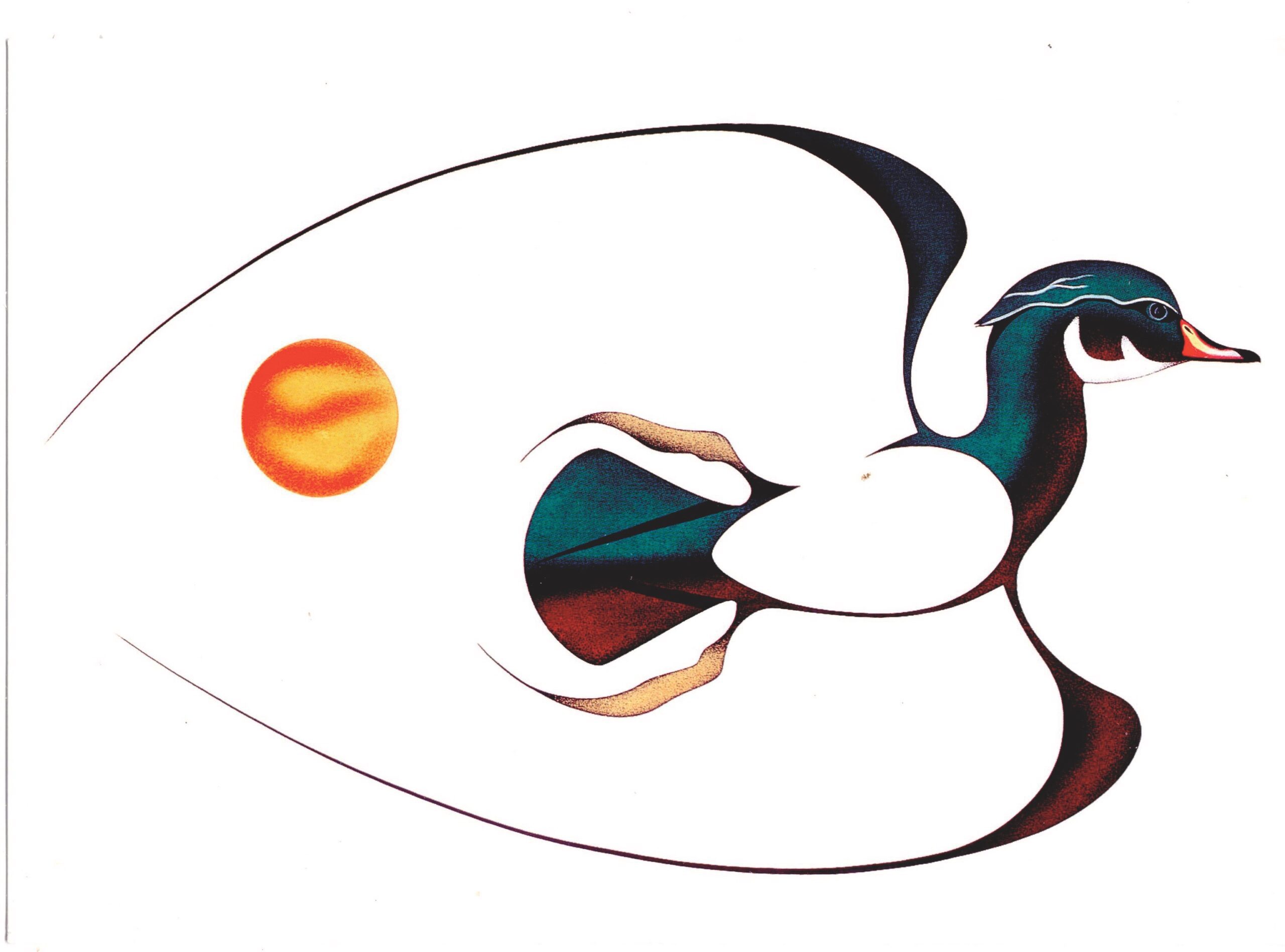

With about 700 communities and more than 1.6 million people speaking over 50 languages, the Indigenous presence in Canada is impossible to sum up in one monolithic definition. Not all communities are powwow people. Stories about Raven differ between the Haida and the Cree. Some canoes are made of bark, and some are dug out. Some communities carve totem poles, and some carve soapstone. Depending on where you want to go, the richness and diversity of our traditions will be evident. I have vivid memories of becoming aware of my identity as a kid. Moments of awkward joy at my first powwow at the Winnipeg Friendship Centre, of seeing my first Isaac Bignell paintings, of sampling Indigenous cuisine at Neechi Commons in the city’s North End and picking medicines in Birds Hill park and other locations near Winnipeg.

Two summers ago, I took in a dinner and performance at the Squamish Lil’wat Cultural Centre in Whistler, B.C., where a young hoop dancer transfixed the audience. I was surprised to find tears running down my face, realizing that it had been over three years since I had seen a hoop dance — a style that is common in Manitoba but not so much in British Columbia. It filled me with joy and pride to see a young Cree man tell a story about his culture.

Communities with an enterprising spirit are offering our history, culture and language to tourists, hoping to fill some large gaps in their understanding of Turtle Island. In 2019, the industry employed 40,000 workers and generated almost $2 billion in revenue, according to the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC). Those numbers fell steeply due to COVID-19, and there’s still uncertainty about what this summer might hold. Some tour operators are waiting for more clarity from officials before deciding to open. Some communities, especially remote ones with limited medical resources, may continue to restrict visitors. But others in the industry are hopeful that a better season lies ahead and have adapted their offerings to meet health guidelines.

ITAC is a good place to start your research of the living cultures of dynamic peoples. To be a voting member of the association, a business must be at least 51 percent Indigenous-owned and have all licences, permits and insurance in place. ITAC’s travel website, destinationindigenous.ca, lists a variety of experiences and tour packages across the country, including details about what’s currently open and closed.

As an artist, I’m compelled to advise you to be wary of souvenir shops and gift stores that prey on tourists and carry “Indigenous” products that are not made by Indigenous people or even made in Canada. The issue of fraudulent First Nations, Métis and Inuit art is a big problem, and all too often, tacky, low-quality and mass-produced knock-offs fill the shelves of souvenir shops. Many art galleries and shops deal directly with artisans, who depend on their craft to feed their families.

Wherever you come across Indigenous art, ask questions about where it was sourced. Reputable businesses have relationships with the creators they represent and will be happy you inquired.

By supporting Indigenous tourism, you won’t just be learning about us, but also about yourself. The desire to experience life more fully is something that brings people to seek wisdom from this land and from the old ways. I find that sitting and sharing some tea and bannock with an Elder is helpful when I have questions or curiosities. Receiving and sharing this wisdom through celebration leaves lasting impacts that can uplift and revitalize communities.

Indigenous peoples’ modern lives are governed by traditional values. But our cultures are alive as we continue to evolve and forge a path forward.

Let’s discover our like-mindedness as neighbours and engage in an exploration that’s uplifting and rewarding for all.

***

Mike Alexander is an Anishinaabe artist from Swan Lake First Nation in Treaty 1 territory in Manitoba, now living in Kamloops, B.C.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2021 issue with the title “Living Culture.”