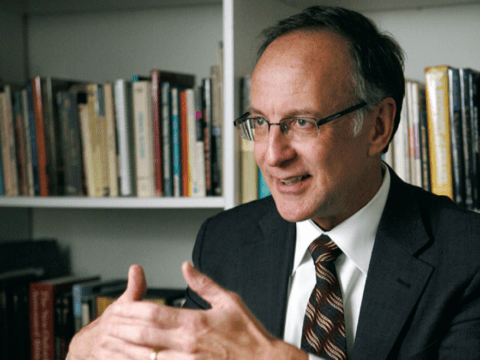

Nobel Peace Prize nominee and former Liberal foreign affairs minister Lloyd Axworthy is a lifelong United Church member. David Wilson spoke to him at the University of Winnipeg, where he has been president since 2004.

DAVID WILSON: You were a student at this university in the early 1960s when it was still a United Church college. Did you ever imagine you’d run the place some day?

LLOYD AXWORTHY: The people and ideas I met when I was a student here have always been part of my texture. I had been faculty from time to time, but no, I didn’t see myself coming back as president. It was not a career tree I was following. But now that I’m here, why not?

DW: You’ve had a distinguished career in public life. Is there any link between what you do now and what you have accomplished in politics?

LA: I have seen what is happening on a global scale — a huge erosion of thoughtful, critical, committed, educated people who really believe in remaking a world gone crazy in so many ways. I really believe in the potential of a university to be a place where you take the young and old and say, “Let’s think seriously about this world we’re in.”

DW: What have you learned in government that can be brought to bear on this agenda?

LA: How to build bridges. The big difference, though, is that I had a lot more resources when I was minister of foreign affairs than I do now as president of a university (laughs).

DW: You’re a lifelong member of The United Church of Canada. To what extent, if any, have the values of the United Church shaped the values you have brought to your working life?

LA: I wouldn’t say that I get up every morning and read Scripture, but there have been times when it has been very important. Kosovo, for example. At the time, I was foreign minister and we were engaged in diplomatic efforts to deal with the ethnic cleansing and killing that was going on. It finally came down to the fact that we were prepared to go in and fight. That really took me to the mat. All the great words about protecting people came down to the question of whether we were willing to go to war to do it. My minister [Rev. James Christie, now the University of Winnipeg’s dean of Theology] and I spent an afternoon in a restaurant on the Rideau Canal talking about just war and a lot of other things.

DW: This university is steeped in the social gospel tradition that underpinned so many of the United Church’s positions on public issues over the years. Can the college — and the church — regain some of that fervour?

LA: The social gospel is an important concept for this university and this region. One of my goals is to restore the life and energy that the department of theology brought to the university as a whole. We went through a period of major secularism at the university when theology wasn’t a priority. Secular humanism still dominates our ethos, but at a time when religion has become so central to the politics and to the economics and social situation in the world, we’re strengthening the faculty of theology and encouraging them to take on an active role as a forum for intellectual discussion and debate. We believe that [former MP and United Church minister] Bill Blaikie coming to the faculty will help achieve that.

DW: Your career has been characterized to a large degree by the global causes you have adopted, such as the landmines treaty, Human Rights Watch and your work as a special UN envoy for Ethiopia. Do you have a global cause right now?

LA: If there is a cause, it is to try to have this generation embrace what this country can do, what it stands for. We have a situation now where Canada seems to have gone right off the rails. I think we were a country that had a certain vocation internationally — to talk about nuclear disarmament, to promote peaceful solutions to problems and to deal with poverty-related issues. We don’t get much of that discussion in this country right anymore. It’s just not part of the political agenda. When was the last time you heard a Canadian politician talk about peace?

DW: Would you consider going back into politics to bring about the kind of change you feel we need?

LA: No. I’m done. I think it’s time for a new generation of politicians. That’s why a place like this university is important. For example, I teach a class on Canadian foreign policy to a group of 15 smart young men and women who are groping to find answers to these issues. Sometimes, it’s the best three hours of the week for me.

DW: What would you like your legacy at this university to be? Do you want this university to produce the next great prime minister or foreign minister?

LA: Or the next moderator (Laughs)? When I leave, I’d like to see this university actively engaged in what I see as the most significant domestic issue of our time, which are the rights of Aboriginal people in this country. We can do it by using the resources of the university to enable people in the Aboriginal communities and their leadership, and to build trust in institutions like this. That would be very satisfying.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s April 2008 issue with the title “‘Canada seems to have gone right off the rails.’”