School supervisor Arthur Henry Plint is tipped precariously far back in a swivel chair, face distorted, eyes wide with fear. At his throat is a knife in the fist of a 13-year-old Gitxsan First Nations boy.

It is spring 1968, at the Alberni Indian Residential School near Port Alberni on Vancouver Island. Early on a weekday afternoon, the school is hushed. Most of the 300 resident students are out of the building in classes at a local public school. But not all. In the office of the boys’ supervisor, a scene is unfolding that encapsulates the raw essence of residential schools: the radical inequality, the depravity, the brutality — and occasionally, a ferocious determination to resist.

Willie Blackwater is speaking to Arthur Plint in a low, controlled voice. “I told him I’d been sharpening the knife for two years and it could cut through bone, and if he moved I’d cut his head clean off,” Blackwater recalls. “I told him I wanted three things. First, quit picking on me: the rape, the extra chores, all that. This torture is coming to an end. Second, I said, when I come back for Grade 8 I want to be boarded out. Some students got to live with families in town instead of in the school, and I wanted that for me. Third, I said, I know it’s not just me. You have to quit abusing the other boys. If you don’t, I’ll kill you. And there are other boys with knives, and if I don’t kill you, they will.” Plint nodded almost imperceptibly, and then soiled himself.

How Blackwater’s revolt had altered things in the short term would soon become apparent. After the incident, Blackwater went home for the summer to his reserve at Kispiox, in central British Columbia, as he customarily did at the end of every school year. When he returned to Alberni in the fall, he was indeed boarded out to a family in town, and he suffered no more sexual or physical abuse from Plint. According to Blackwater, Plint had always had a drinking problem; after the encounter in the supervisor’s office it spiralled out of control, and he was dismissed in the first few months of the new term.

The long-term impact of the encounter would not be fully understood for decades. The experience taught young Willie Blackwater that you can fight back, a discovery that would shape the rest of his life. It was the first in a series of critical acts of resistance that Blackwater would spearhead against the despised Indian residential school system, acts that would ultimately trigger the national truth and reconciliation process and perhaps a new day in relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

Blackwater recalls the day in 2010 when Murray Sinclair flew from Ottawa to Abbotsford, B.C., and asked Blackwater to drive up from Chilliwack, B.C., (where he was then living) to meet him. Sinclair is a Canadian judge, First Nations lawyer and the chair of the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“He gave me a big hug and said, ‘It’s an honour to meet the man who put the residential schools issue where it’s at. We’ll show the world what truth and reconciliation is really all about.’” Says Blackwater simply, “I cried.”

“I don’t mind sharing my story,” Willie Blackwater tells me as we wend our way in his pickup truck through the steeply sloped streets of Gitsegukla, a Gitxsan reserve on the Skeena River in B.C.’s interior. “It helps understand what we’ve been through and explains why we are the way we are,” he says, without need of further elaboration. Looking out the window it’s easy to get his drift. Gitsegukla, population 500, is desperately poor. Some of the hamlet’s bungalows look presentable, but others are abandoned and falling down. The United Church building in the centre of town looks distinctly shabby, in need of repair and more than just a lick of paint.

Blackwater lives on a hill overlooking a soccer field and a small cedar-panelled school and recreation centre decorated in the red and black colours of West Coast Indigenous art. He gets the prized location, he explains, by virtue of his recent election as village chief. Eighty percent of his constituents are unemployed, he tells me matter-of-factly, as we wheel onto the highway heading west to Kitwanga, another reserve town 21 kilometres away. The restaurant attached to the Kitwanga Petro Canada service station serves up the best bacon and eggs in the region, Blackwater promises.

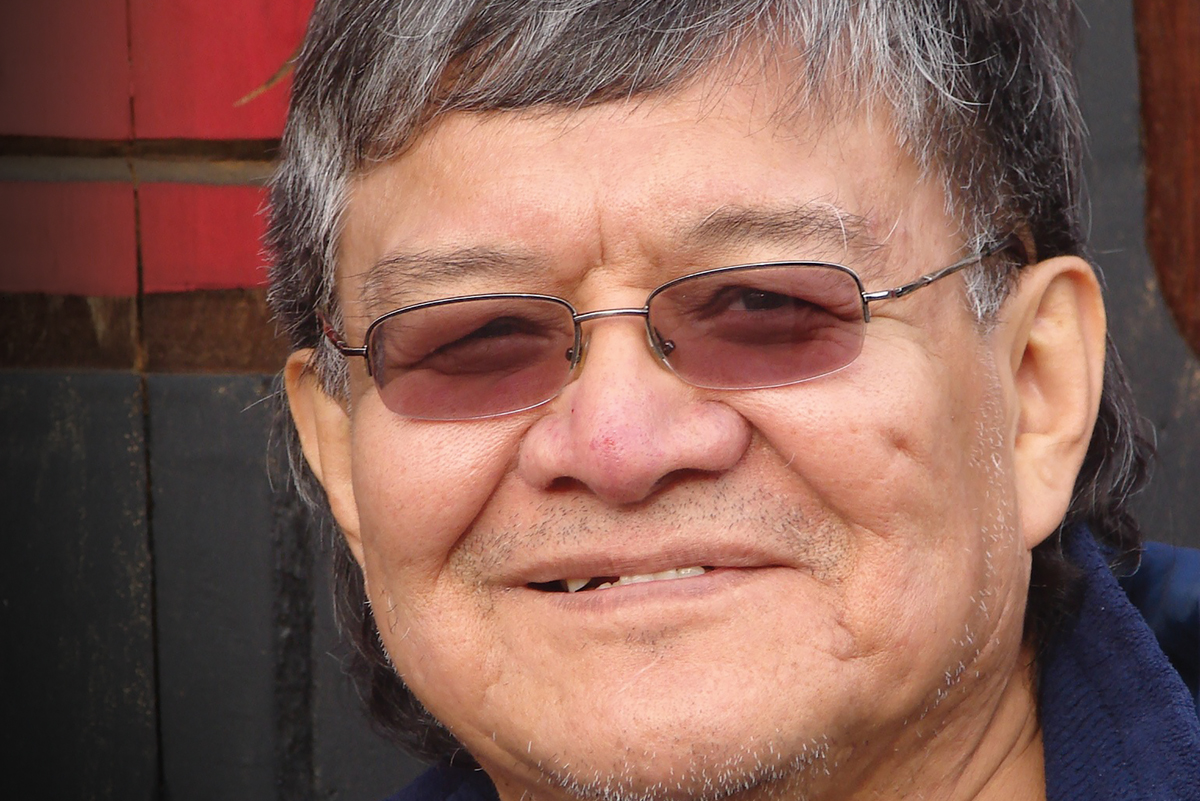

Five-foot-three and greying, Blackwater doesn’t particularly look like a hero. His chief’s regalia on this frosty November morning consist of a T-shirt, patched jeans and a blue and grey Columbia coat. Crossing the parking lot to the Petro Canada restaurant, he moves nimbly for his 61 years. Blackwater’s is not a classically handsome face, but it’s strong, etched with character. His hands, resting on the Formica tabletop, are toughened from a life of hard labour.

When Blackwater speaks of his early years, he makes them sound almost idyllic, despite some obvious hardships. “My biological mom died when I was three,” he says. “After that, my biological dad, Walter, pretty much went AWOL. He never touched a drop before she died, but he made up for it after. Walter was around, but for years I thought he was my brother.”

Blackwater was raised in Kispiox by his grandfather, who died when he was young, and his grandmother, Mary Blackwater. “I called them Dad and Mom.” Kispiox is one of the reserve towns of the region, located north of Hazelton. Mary Blackwater was a highly respected elder; a street that runs through town is named after her.

The elder Blackwaters made sure Willie and his siblings learned the Gitxsan language and customs. “English was never spoken in our home,” Blackwater says. The children were also exposed to Christian traditions. Every Sunday, Mary would suit Willie up and slick back his hair before taking him to Pierce Memorial United, a handsome white frame church situated at the confluence of the Kispiox and Skeena Rivers. It shares the high riverbank with a row of magnificent totem poles made famous by painter Emily Carr. Some of both traditions stuck. Blackwater still speaks Gitxsan, and still adheres to the United Church. “I got married in the United Church, and I’ll be buried in the United Church,” he says.

Childhood in Kispiox was not lavish, but neither was it destitute. “I hunted moose with my grandfather. We trapped marten together and other furs to sell. My grandmother taught me how to catch and smoke fish. We had a simple garden and grew our own vegetables, and picked wild berries.”

In summers, the entire family — including Willie and his two older brothers, stepbrother and three cousins who were raised by the elder Blackwaters after the death of his aunt — would move to Prince Rupert, B.C., on the coast to work in the Cassiar fish cannery. In winter, his grandmother would lead ice-fishing expeditions on the frozen Skeena River. Mary would light a fire and brew tea to wash down cold baked potatoes, baked beans, fried bread and “burnt fish” (wholly smoked skin-on sockeye salmon roasted on sticks over the coals until the skin chars and falls away). Blackwater says these trips are among his favourite childhood memories.

Managing the big family was especially hard for Mary Blackwater after the death of her husband. But for Willie, it worked. Not so for the Indian agent on the reserve. “Kids were chosen [to be sent to residential school] by the Indian agent if they came from what he thought were ‘dysfunctional’ families. Both parents not living, or not living together, meant, by definition, ‘children at risk,’” Blackwater says. He and all of his siblings were caught in that net. Some were taken to the residential school in Port

Alberni, others to Alert, at the north end of Vancouver Island.

“I was 10 years old when I was sent away.” Blackwater remembers the journey vividly. It was a three-day, 1,400-kilometre trip by bus, he says. “The bus started in Prince Rupert and stopped at Terrace [B.C.] for the Nisga’a children, then onto Kitimat and

Hazelton [B.C.] for the Gitxsan and Wet’suwet’en kids. We ate and slept on the bus. Kids were crying. I cried myself on that first trip. They hauled us there like sardines.”

“Between life ‘before’ and life ‘after,’ there was absolutely no connection,” Blackwater says. Far from the riverside picnics with his grandmother, Blackwater found himself walking the dehumanized corridors of the Alberni Indian Residential School, dining on oatmeal mush, lumpy powdered milk, and, on good days, sandwiches made of “green meat.”

“I hated it all,” says Blackwater.

All? “Well, there was sports,” he says. “I liked the sports: soccer, hockey, basketball.” Basketball? At 5’3? “I used to be sent in to agitate the taller, better players on the other team, to get them to foul out. I was a pest. The thorn in their side. Story of my life,” he laughs. “Played defence in hockey. I could take a lot of pain.”

Within days of arriving at Alberni, Blackwater says, he was called into Arthur Plint’s office to “take a phone call from my father.” It was a ploy to get him alone and marked the beginning of the sexual and physical abuse. When he went home that first summer, Blackwater told his father what was happening. “He thought it was a story to get out of going back.” He surmises that Walter Blackwater must nevertheless have said something to the school, because when he returned to Alberni in the fall, Plint soundly beat him. Lesson learned.

The abuse continued. Blackwater’s anger went underground. He acted out, became obstreperous. Gilbert Johnson, at the school from age six to 16, was Willie’s friend. He confirms Blackwater’s tough-guy self-image. “If someone gave him trouble, he wouldn’t back down,” Johnson says.

“I was a bit of a troublemaker,” admits Blackwater, “so for that I got given the worst job: peeling potatoes in the kitchen.” There was an eventual upside to the potato peeling. “I had access to the kitchen tools, and I took a knife. I sharpened that knife for months, for a year and a half actually, until it was so sharp you could slice a piece of paper with it. Then, in late spring of Grade 7, I told Plint I wasn’t feeling well and didn’t want to go to school.” At that time, students were being bussed from the residential school to a public school every day for classes. “Plint said, ‘You don’t look sick’, and I admitted I really wasn’t. I told him I wanted to stay with him. When he heard that he just beamed.

“He took me to his quarters. He made me lunch, the best meal I had in three years at the school,” Blackwater says. “After lunch he took me into his office. That’s where he always liked to start. I played along with him. He was sitting in his chair totally relaxed.” That’s when Blackwater pulled the knife from his boot.

The confrontation that marked the beginning of the end for Arthur Plint also marked the beginning of a life of resistance for Willie Blackwater.

“It was the best day of my life,” he says. “When he shit himself, sitting there in his big office chair, I knew he’d heard me and believed me. He knew I meant every word.”

With Plint gone, the worst of the sexual and physical abuse ended, but the isolation, loss of language, tradition, connection to family and community remained. “The culture they took us from is the main thing,” Blackwater says now, bitterly twisting a metaphor: “The physical and sexual abuse was just the icing on the cake.” Over the next six years, those big losses had their intended effect: to erode his spirit, to “kill the Indian in the child.” The door to the Alberni residential school finally shut behind Blackwater at age 18. By that time he was a textbook case of the long litany of harms the residential school system was capable of inflicting.

Blackwater’s community was lost to him. “I had this hatred for Kispiox because I didn’t think they had cared for us very well,” he says. “I never went back, and nor did any of my biological siblings.” Blackwater’s family was fractured. He was estranged from his father for most of the rest of his father’s life, angry with Walter for giving him up and for the added insult of replacing him with an adopted stepson, a distant relative, who enjoyed all the benefits of a home life in a caring community that Blackwater had lost.

Fresh out of school, Blackwater drifted from job to job. He worked at the Cassiar Cannery near Prince Rupert until it stopped packing salmon in 1982. He then moved on to a job as a logger in Nisga’a territory in the Nass Valley, B.C., where he met a Nisga’a woman. They had a child they named Leroy after another of Blackwater’s friends from Alberni. When Leroy was three, his mother took him and ran away, fearful of Blackwater’s violent anger.

Blackwater moved on to Kitimat, still as a logger, but with a sideline in marijuana. When he got caught, his aunt persuaded the judge to let her take him home to South Hazelton on probation. Blackwater worked in sawmills in South Hazelton and Carnaby, B.C., as a forklift operator and later as a loader operator until he could afford to go into business for himself. He says the business went well enough for three or four years until he started to hallucinate. He thought he could see Arthur Plint’s face reflected in the window of his loader, and flipped the machine twice before he sought psychiatric help.

One evening in 1993, Blackwater came home from work to hear from the babysitter that a 14-year-old foster child Blackwater had brought into his home had been sexually abusing Blackwater’s nephew. Blackwater exploded. “I lost it. I beat him,” he admits. “The police were called. The boy was taken out of our home, and there was a two-year-long investigation.

“It was the first time I had shared my experience with Plint with anyone outside my crowd of classmates.”

“In the end, the RCMP dropped all charges, but near the end of the process [Const.] Al Franczak, the officer in charge, asked me if anything of this sort had ever happened to me.” Taken off-guard, Blackwater blurted out the excruciating truth. “It was the first time I had shared my experience with Plint with anyone outside my crowd of classmates.”

To his credit, Franczak followed up on Blackwater’s confession. “[Franczak] asked me if I wanted to make a statement. He told me there was no statute of limitations on that kind of crime. He came back to talk to me several times before I agreed. It was so emotional for me.” Blackwater speaks of Franczak, now retired, with obvious admiration. The admiration is mutual. Franczak says that he was particularly struck by the quiet restraint of Blackwater and the others who agreed to come forward. “I just did my job,” Franczak says. “Willie and the others were the heroes for going through all they had to go through.”

Franczak tracked Plint down in Victoria. The case went to trial in 1994. Plint pleaded guilty to 18 counts of indecent assault, and in March 1995 he was sentenced to 11 years in prison, where he would die of cancer in 2003.

Because Plint entered a guilty plea, the trial was all over before Blackwater and 15 others could tell their stories. That was a source of deep frustration to them, Rev. Brian Thorpe recalls. As the United Church’s top official in British Columbia at the time, he watched the proceedings closely. “To be able to stand up in a court of law and be believed would have been a great thing,” he says, “but when Plint pleaded guilty it robbed them of the chance to do that. After the criminal suit there was virtually no public reaction. It was over so quickly it barely registered.”

Dissatisfied, Blackwater and his comrades turned to lawyer Peter Grant, at the time working out of a trailer parked in Hazelton. Grant was a crusader who had made an early decision to put the law to use to help the marginalized. He was in Hazelton (known as Gitanmaxx to the First Nations of the region) to establish a Native Community Law Office. He had known Blackwater’s family for years.

When the criminal trial abruptly ended, Grant says, “Willie and the others, 30 in all, came to me and said, ‘We want to do more.’ What ‘more’ was, was not well-defined at the time.” Eventually the group decided to launch a civil suit against the federal government, which owned the Alberni residential school, and the United Church, which operated it. It would turn out to be one of the most pivotal civil suits in Canadian history.

“The plaintiffs had to decide whose name was going to lead,” recalls Grant, “and Willie’s name was it, probably by dint of his strong personality. He’s a very outspoken, plain-talking guy.”

Blackwater downplays the leadership role handed to him: “I can’t really accept it,” he says. “It’s not really about me. It’s about anyone who doesn’t have a voice.” But there is no doubt Willie Blackwater’s instinct to fight back propelled the civil suit. And as much as he may play down his own importance, when he speaks of the lawsuit, he seems to take possession of it. “When I started the civil suit I was motivated by anger and frustration,” he says. “Part of my anger was directed toward the church, my church. During the criminal prosecution, the United Church did not show up to support us. Neither did government. It seemed as if nobody really gave a shit, either when we were in school, or later during the court case.”

Thorpe says the church was there, but acknowledges, “local United Church ministers in court didn’t self-identify. The church should have stood up and been seen to be present and supportive, but it didn’t.” When I tell Blackwater that there were United Church ministers present, he says, “Things might have been different had we known.” It is mind-boggling to imagine the course history might have taken if indeed things had gone differently and Blackwater v. Plint had not gone to trial.

There were 28 plaintiffs when the case began in the B.C. Supreme Court in February 1998. By the time proceedings in Nanaimo wrapped up, 21 plaintiffs had settled out of court, including Blackwater. “The civil suit was harrowing for all the plaintiffs,” says Peter Grant. “It was a case of be-careful-what-you-wish-for. Making up for the opportunity lost in the criminal case, everybody wanted to get up and tell their story. Then — surprise, surprise — they were cross-examined.”

Initially, the church and government lawyers played hardball. “The process had a horrific impact,” says Blackwater. “Some of us reverted to our drinking and other coping mechanisms. Two plaintiffs died during the trial. My friends. It was never my intent to see people further damaged. I talked to Grant. I said, ‘If I had known the toll this would take I’m not sure I would have done it. Can you negotiate a settlement?’ He did. I withdrew.” The terms of the out-of-court settlements are confidential. But it is a matter of public record that six of the remaining plaintiffs were awarded amounts ranging from $10,000 to $145,000.

The trial spanned three years. In a precedent-setting decision partway through, B.C. Supreme Court Justice (later Chief Justice) Donald Brenner ruled that the government and the church owed a duty of care to Plint’s victims and were therefore indirectly, or vicariously, liable for the harm he caused, and on the hook for damages. He would later assign the government 75 percent of the liability, and the United Church 25 percent.

Before Blackwater v. Plint, “There may have been a few hundred residential school cases coming from all over the country” according to Professor Jim Miller of the University of Saskatchewan, one of the first historians to study residential schools seriously. The Blackwater case gave hope to thousands of other residential school survivors who had long despaired of ever having their stories heard or being compensated for the harm they suffered. “By early 2001, some 8,500 former students were engaged in litigation, the financial liability for which might well exceed $1 billion,” says Miller. By 2005, when the Supreme Court of Canada upheld Brenner’s ruling, there were 14,000 cases.

Peter Grant relates a telling anecdote. He says that he was in regular touch with CBC News reporter Terry Milewski, then stationed in Vancouver. “Terry was talking to me throughout the trial,” Grant says. “The penny finally dropped. ‘This is one of the biggest cases in Canada’ he said, though it was really a question not a statement. ‘Yeah, it is’, I said. ‘This is huge,’ he said. ‘This is not just one school and these 20 people. This is about all students in all residential schools across the country.’”

From its vantage point at ground zero, the United Church had already figured this out, says Virginia Coleman, the United Church’s general secretary from 1994 to 2002. “We didn’t know what was going to happen. Willie Blackwater and his lawsuit certainly pushed the button to make the church and government take notice.”

Historian Miller thinks the Blackwater case forced the churches to lobby for a comprehensive out-of-court settlement to avert fiscal ruin. “The success of the Blackwater case was a powerful incentive to act, to find another way,” he says. For the United Church, finding another way would come to mean more than focusing on damages for physical and sexual abuse. Increasingly influenced by its Indigenous members and Canada’s First Nations leadership, the church slowly came around to the position, advanced but dismissed in Blackwater v. Plint, that systemic harms such as forced removal and loss of language, culture and community also needed to be addressed. A class action lawsuit launched by the Assembly of First Nations against the federal government in 2005 finally brought Ottawa around to the same conclusion.

On June 11, 2008 — 10 years after Willie Blackwater and the Alberni plaintiffs told their stories for the first time in a Nanaimo courtroom — then prime minister Stephen Harper stood up in the House of Commons and apologized for residential schools and the policies of assimilation that underpinned them. Two years later, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission held the first of its seven national events, raising hope that the wounds residential schools inflicted on First Nations might finally begin to heal, and that non-Indigenous Canadians might at last come to grips with a shameful chapter in the nation’s history.

Blackwater and the other Alberni plaintiffs “took the lead long before the TRC was even thought of,” says lawyer Grant. Thorpe, who served as the United Church’s senior adviser on residential schools from 2000 to 2005, considers Blackwater’s place in history: “Is he a Canadian hero? It would be quite reasonable to call him that,” he concludes. “We have to keep reminding ourselves of how difficult it is to talk about childhood abuse. Willie took the risks.”

Blackwater made his peace with his father just before he died. He has not yet reconciled with his estranged son, Leroy, though he continues to try. “I guess he’s just not ready,” he says, then laughs to hear the echo of the Tory attack ad from last fall’s federal election. And then he has to pause to wipe a tear from the corner of his eye. Losing a son is nothing to laugh about. “I’m alright,” he assures me, still the pint-sized hockey player who can absorb a hit.

I found myself typing the closing paragraphs of this story on the very day last December that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its full, six-volume final report. It takes 2.3 million words to detail everything Willie Blackwater was trying to say with the finely honed edge of his kitchen knife decades ago.

In light of the TRC, I ask him if he felt he now has closure — if he has finally, really, won. “It depends on what you mean by winning,” he replies. I ask what winning means to him, and he says he won’t rest until his people’s culture has been restored: “Until our descendants have what our ancestors lost,” is how he puts it. “What was taken away must be returned.”

Can that ever happen? Blackwater himself has become a traditional drummer, recapturing a custom his grandmother introduced him to in the communal hall in Kispiox. He is immensely proud of his daughter, Latishia, (by his second wife) and his granddaughter, Abigail, who have both learned traditional Gitxsan dances. But he is sad that neither speaks the Gitxsan language. Blackwater has to face the likelihood that Gitxsan children will never trap marten or eat burnt fish and boiled potatoes on the frozen Skeena River like he did. His irresistible force may have collided with the immovable fact that time can never be turned back.

This story first appeared in the March 2016 issue of The Observer with the title “The fighter.”

How much downplay on charges of rape to indecent assault and the other stories of murder of children and the stay of evidence that the complainants spoke of how unjustified and after pouring their hearts out, tellings of wound-opening stories and given a bandage and sent back to their isolated community to suffer alone and turned to suicide for relief. Thanks, Canada. I witnessed this and their stories. Gordon Gillis