John Porter’s The Vertical Mosaic, a landmark of Canadian history published in 1965, includes a relevant reference to The United Church of Canada: “In many respects it is as Canadian as the maple leaf and the beaver,” he wrote. Porter couldn’t envision what was beginning the very year his book came out: the church he saw as so Canadian was on the eve of a decline that wouldn’t cease, dropping from roughly 1,064,000 members in 1965 to just under 464,000 in 2012. The rate of decline is accelerating.

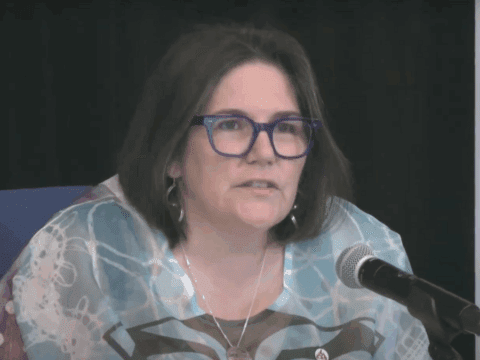

Now a deeply engaging work by United Church academic Phyllis D. Airhart, professor of Christian history at the University of Toronto’s Emmanuel College, looks to the church’s past and present. Titled A Church with the Soul of a Nation: Making and Remaking the United Church of Canada, the book is a major achievement, remarkable for both its breadth of research and its interpretive insight. Airhart argues that, as Porter sensed, the United Church was formed with a special future in mind: an obligation to help steer Canada to a future of Christian character and responsibility.

Most of us believe that June 10, 1925, marked the birth of the United Church. In terms of the calendar, this is true, but in terms of the church’s creation, not exactly. As Airhart observes, the spirit of union was already in the air in 1874 when Presbyterian minister Rev. George Monro Grant spoke to a Montreal audience on the topic, “The Church of Canada — Can Such a Thing Be?”

Fifty years later, the Winnipeg minister Rev. C.W. Gordon, a Presbyterian who wrote novels under the name Ralph Connor, described his support for church union in patriotic terms: “I’m a church unionist not because I like the union so well but because I am a Canadian and love my country and I see in this union what is best for Canada.” This perspective — that the United Church would foster a better country — lived on into the 1960s, Airhart writes. The United Church conceived itself as “for the friendly service of the whole nation,” as an early Home Missions report put it.

In The United Church of Canada: A History, a recent and highly readable essay collection edited by Rev. Don Schweitzer, Rev. John H. Young of Queen’s University describes the period beginning in the mid-1940s and lasting until 1960 as a “golden age” for the church. Young begins with an optimistic day in 1959 when the United Church’s new national headquarters on Toronto’s St. Clair Avenue was dedicated. For the 20 percent of Canadians then affiliated with the United Church, the building was “a sort of symbol of their church’s strength, growth and future,” The Observer reported confidently. Yet just a few years later, The United Church of Canada would begin its sober decline. (The headquarters building was later bulldozed, making way for a condominium project.)

How did a church with nation-shaping dreams ultimately fall short of its goal?

As Airhart observes, by the 1960s, Canada itself was much different than what the original unionists had imagined. Sunday was quickly being recast as a day of recreation rather than worship. Meanwhile, Canada’s demographic makeup was profoundly shifting as immigrants flowed in from around the globe. And those who migrated from traditionally Christian countries in Europe were already largely secularized by the time they arrived, and thereby disinclined to church membership. In the midst of this cultural revolution, Airhart writes, United Church leaders were left grappling “with the realization that creating a Christian Canada was unlikely — and perhaps even undesirable — in a pluralistic and segmented world.”

By 1965, with the earliest evidence of membership decline, the General Council secretary Rev. Ernest Long made a courageous prediction: if the United Church didn’t change its ways, it was headed for a “stunning defeat,” he warned.

One of the biggest shifts in the church’s identity was to distance itself from evangelism as a path to justice. Throughout much of its history, especially prior to the 1950s, the United Church had worked hard at articulating Christian faith as both personal and social. “Decades after the United Church was inaugurated,” Airhart writes, “a new generation of leaders would still praise as wise the decision not to separate moral and social concerns from evangelism.” But it was not to be. To many contemporary Canadians, evangelism meant Billy Graham’s call for personal salvation, not the United Church’s vision of a Christian social order in which the poor and the excluded become full participants. By the end of the 1960s, Airhart writes, “to be a liberal evangelical was almost a contradiction in terms.”

The United Church culture began to change deeply in other ways too. In the mid-1960s, the church’s historic Sunday school booklets were replaced by the New Curriculum, which reached 90 percent of congregations, seeking to present Christian theology with modern insight and candour. Sadly, the appeal to the new generation didn’t work. As Airhart records, three years after the New Curriculum’s introduction, Sunday school enrolment had declined by a sharp 25 percent, a trend mirrored in denominations across North America.

Airhart’s book is both constructive and painful. She offers specific possibilities as to what sparked the church’s crisis in membership, but the overarching cause seems clear. What happened in Europe, made so vivid in Britain, had come to Canada. The best-known book on the subject, The Death of Christian Britain by religious historian Callum G. Brown, predicts on its introductory page an unpleasant truth: the great decline of Christianity in Britain is “emblematic of the destiny of the whole of Western Christianity.”

Airhart is a historian, more comfortable with assessing the past than predicting the future. But for me, the United Church’s institutional waning needn’t mean The End. It means we are embarking on a great transition, one that over decades will lead to new faith formations, the outcome of the stewardship of countless Christians who went before us.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s April 2014 issue with the title “‘Canada’s church.’”