Dementia has been described as a long goodbye. A thief in the night. A slow unravelling. Being locked in a broken time machine. Looking in a mirror with a fading reflection.

For many who fear developing the condition, it’s not just the prospect of losing oneself and one’s memories. It’s also having to go into long-term care: being bathed and dressed by strangers in a locked ward, passing dull days with only occasional visits from adult children. Family members, too, fear the pain of seeing people they love living with dementia: a bewildered father withdrawing from the world because simple conversation is too difficult or a mother expecting her long-dead husband to walk through the door any minute.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

But if the prospects are scary, so is the stigma. Sixty-one percent of Canadians told Leger pollsters in 2018 that they believe they would face discrimination of some kind if they developed dementia; 46 percent said they would feel ashamed to develop the condition; and 25 percent believe their friends and family members would avoid them.

Today, almost 800,000 Canadians live with dementia, more than 60 percent of them female. A third of women who reach 90 are likely to have dementia. More than half the caregivers of those with dementia are female. And while the prevalence of the condition remains stable, the number of cases is increasing because dementia tends to affect older people — and by 2030, seniors could represent almost a quarter of the Canadian population. In the next 25 years, cases of dementia here are projected to reach more than 1.7 million.

Around the world, they’re expected to nearly triple during that same time frame, reaching 153 million, up from the latest estimate by the World Health Organization in 2021 of 57 million.

As dementia becomes more ingrained in the social and medical fabric, a cultural revolution is emerging in how the condition is being managed and treated. Technology is playing a greater role. Cities, towns and even parts of the travel and hospitality industries are reconfiguring themselves to earn dementia-friendly designations. Some long-term care facilities are experimenting with unlocking the wards and relying less on pharmaceuticals. All those trends mean that over the next 25 years, people with dementia can expect to enjoy an improved quality of life, have greater independence and be more connected to community.

Most transformative of all, though, is the complete reimagining of dementia — not as a tragic end, but as a different kind of beginning. Many experts believe that over time, the stigma surrounding the condition will fade. Fear and avoidance will be replaced by acceptance and empathy. People living with dementia will be recognized as valuable members of society.

The hope, says Dr. Allen Power, the Schlegel Chair in Aging and Dementia Innovation at the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, is that people with dementia and their loved ones will not dwell in sorrow over what has been lost, but will find meaning in the humanity that remains. The thought echoes the sentiment of Romantic poet William Wordsworth: “Though nothing can bring back the hour / Of splendour in the grass, of glory in the flower; / We will grieve not, rather find /Strength in what remains behind.”

But how to get there? Power, who is a geriatrician and a leading dementia expert, argues that we need to dig more deeply into the roots of the distress that patients with dementia often display. People who care for those with dementia see their patients’ distress as a function of diseased brain cells and chemical imbalances, so they often prescribe drugs. Power points to research that shows about 30 percent of people with dementia in U.S. nursing homes are prescribed antipsychotics to ease their anxiety.

But sometimes those drugs can cause greater confusion, falls and even death. “I think antipsychotics are what I would call the restraints of the 21st century,” he says.

In his books Dementia Beyond Disease: Enhancing Well-Being and Dementia Beyond Drugs: Changing the Culture of Care, Power argues against the overuse of medications to control dementia-related behaviours. Instead, a person with dementia needs an environment that fosters engagement, dignity and respect. And people caring for them need to understand that distress is often the expression of unmet needs. “We need to change our minds about people whose minds have been changed,” Power says, adding: “Drugs are not the answer.”

The primary goal should be to enhance what he calls “domains of well-being,” which include preservation of an individual’s identity, a sense of connectedness, emotional security, autonomy, meaning, security, personal growth and joy. These domains, he says, should be “the central issue in improving the lives of people with dementia.”

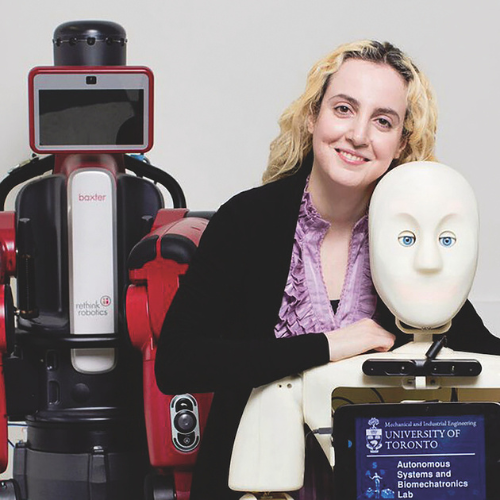

For many elderly people, “domains of well-being” translates into a desire to stay in their own home. It rarely turns out that way. Only about 15 percent of people in Canada are able to die at home, some with palliative care, compared to the 75 percent who want to. Emerging technologies may help. Robot companions, powered by artificial intelligence, will make aging in place a greater possibility for people with dementia, says Goldie Nejat, Canada Research Chair in Robots for Society and the founder and director of the Autonomous Systems and Biomechatronics Lab at the University of Toronto. She is cradling her two-month-old son in her arms over Zoom while she explains the potential for round-the-clock, tech-enabled dementia support.

The bots she’s developing can be programmed to individual users’ needs and behaviours. For example, they can prompt those with dementia to brush their teeth, take them through step-by-step instructions to make a meal, help select suitable items of clothing from their wardrobe, demonstrate exercise routines, detect falls and dispatch alerts if someone has wandered off. They can play games such as Bingo or even dance with their human companions.

Nejat says she wants to create robots so intelligent that their elderly charges with dementia will form a strong attachment and be less dependent on family members. At the moment, family and friends provide more than 580 million hours of care a year to Canadians living with dementia, or the equivalent of 290,000 full-time jobs, according to the Alzheimer Association. Nearly half — 45 percent — show symptoms of distress from the responsibility.

“There’s a lot of stress for caregivers in their 40s and 50s who are in the middle of their careers, raising children and caring for aging parents at the same time,” Nejat says. For those with ailing spouses, many “won’t even leave the house to go grocery shopping or to see a friend. This takes a toll on their mental health. If these robots can assure them that their parents and spouses are okay, it will give them more peace of mind,” she says.

But the robotic possibilities go beyond safety or staying in one’s own home. Lillian Hung, Canada Research Chair in Senior Care at the University of British Columbia’s School of Nursing, says her research proves that robots can also make people with dementia happier. She spent two years in negotiations with a Japanese start-up company to bring their LOVOTS (short for “love robots”) to the university in 2023 as part of a year-long research study in her Innovation in Dementia and Aging Lab. The goal was to go to eldercare settings to test the robots’ impact on relieving boredom and boosting engagement in people with dementia. The machines are enhanced with artificial intelligence and equipped with sensors that allow them to respond to emotional cues. They coo when touched, laugh when tickled, raise their arms to be picked up, sing, dance and follow a person around like a loyal pet.

Loneliness, anxiety, agitation and medication use declined, while overall quality of life improved in older adults, she found. “Social robots aren’t purely functional; they’re designed to respond to people,” she says.

Take, for example, the interactions between a LOVOT named Mango and elderly residents in a long-term care home in British Columbia, part of Hung’s research published earlier this year in the Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering. Mango is 43 centimetres high and weighs about four kilograms without clothing. (Yes, it can be dressed up.) “Some actively called out to the robots, picked them up, petted and rocked them like a baby, and told the robots stories about themselves,” reports the study.

Peter, a resident with cognitive decline, “waved goodbye and blew kisses” when Mango moved away from him. When Ann, a resident with dementia who had largely withdrawn from verbal communication, attempted to put her glasses on Mango, Ann “erupted in giggles, her laughter escalating into joyful tears.” Holly, a resident with cognitive impairment, shared her thoughts about the robot: “The human face may have too complex expressions, confusing to understand sometimes. The robot is clear. It is always happy to see me. It gives me absolute assurance that I am okay. I know I will always be accepted.”

Another bonus of robots? They have unending tolerance for the constant questions people with dementia often pose. “They will repeat the same answer over and over again with a smile on their face,” says Hung. “It’s not exhausting for them. The robot is always polite and doesn’t get impatient.”

She points to the popularity of humanoid robots in elder care in Asian countries such as Japan, China and Singapore. On a research visit to a nursing home in Singapore, she witnessed an older woman with dementia clutching a robotic device shaped like a doll. “It was embedded with a recorded message from her son who said he loved his mother. The mother would not let go of that doll. She kept pressing the button so she could listen to her son. It’s such a simple thing, but it was so comforting to her.”

Hung keeps a pocket-size companion robot in her home that asks her about her day when she gets home from work, checks the weather forecast, provides appointment reminders and even demonstrates emotions. It perks up, for example, when she caresses it. “These robots thrive on love and interaction — they are there to engage humans,” she says, adding that it works both ways. Humans, too, enjoy giving love. “It gives us a sense of joy when we have opportunities to do so.”

Robots won’t be just for the rich. You can already buy a robotic pet companion for about $200. Nejat expects that humanoid robot companions will be available in a few years and cost about $2,000. Twenty years ago, the same technology, had it existed, would have cost about $500,000, she said.

More on Broadview:

- It’s time we start learning to enjoy the aging process

- 3 centenarians on what a lifetime of faith has meant to them

- How boomers are personalizing their last chapter

Both Nejat and Hung reject the idea that robots will eliminate human interaction and take away jobs. “Robotic caregivers will not replace human connection, but instead, they will help alleviate the physical burden on family caregivers and health-care professionals and create positive experiences for those living with dementia,” says Hung. Robots can also help alleviate staffing shortages in long-term care homes by, for example, flagging down a nurse if they detect someone falling or providing one-on-one interactions when staff are busy.

Other emerging technology could also play a role for residents with dementia in long-term care homes. Virtual or augmented reality technology can simulate rich sensory experiences from the past, allowing people to be transported back to their childhood home or to a favourite travel spot. Studies have shown this kind of “reminiscence therapy” can lead to significant improvements in both psychological well-being and cognition among adults with dementia. Augmented reality has been shown to improve the lives of people with dementia by helping them navigate their surroundings and improve communication.

***

Jim Mann, 76, of Surrey, B.C., has lived with a specific type of dementia since he was 58 years old. Sometimes he gets lost walking around the block of his condo, so he brings a slip of paper with him to remind him where to go and wears a bright green lanyard speckled with yellow sunflowers that reads, “Please be patient. I have Alzheimer’s.” He’s soft-spoken and grey-haired — and a passionate advocate for living well with dementia. He regularly does media interviews on behalf of the Alzheimer Society of Canada and its B.C. arm and gives talks in the community.

He was one of the advisers on Hung’s LOVOTS study and is involved in several other dementia research projects.

He’s watched attitudes to dementia evolve over nearly two decades and is encouraged by the possibilities of new technology. But he’s also a fan of the innovations already taking place, including the rise of dementia-friendly communities designed to accommodate the needs of people with cognitive impairments. It’s all part of the trend toward removing the stigma of this condition. “I want people to know there is life after diagnosis, and it can be a very good life,” says Mann, a former marketing executive with Canadian Pacific Air Lines and member of Knox United in Vancouver.

West Vancouver, for example, introduced training for municipal staff and community education workers and made parks welcoming to people with cognitive impairments. The project led to the Alzheimer Society naming it Canada’s first dementia-friendly municipality in 2023, part of a national program aimed at fostering cultural shifts in attitudes toward dementia. The society also recognized the Vancouver International Airport for offering dementia training to its airport volunteers, creating a travel rehearsal program to allow passengers to book a time to visit the airport before their scheduled travel, and participating in the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower program, which, like Mann’s lanyard, signals to staff that a traveller has dementia and may require extra care.

Other airports, too, as well as cruises, hotels, restaurants and attractions are beginning to cater to this demographic, which is often well-heeled.

Religious institutions, including some United Church congregations, are also taking action. The Alzheimer Society’s Blue Umbrella program teaches religious organizations and community groups how to be inclusive and communicate with people with dementia. “Dementia may rob a person of their memory, but it doesn’t take away their ability to connect with God or experience spiritual fulfilment,” says Jane Kuepfer, a specialist in spirituality and aging at the University of Waterloo’s Research Institute for Aging. “We must create spaces where individuals can feel spiritually supported, whether through prayer, music or just being present with a compassionate listener.”

Danah-Lee Krieger, music director of Trinity St. Andrew’s United in Renfrew, Ont., who leads a monthly dementia-friendly choir, says she has been profoundly moved to see how music can comfort people with severe memory loss. When her choir members sing Amazing Grace, they remember every single word, even if many of them can’t name their children. “In all my years of being a musician, I have never experienced anything so miraculous. It brings me to tears, it’s so touching,” Krieger says. “The experience of leading this choir has deepened my own sense of spirituality.”

Some long-term care spaces are changing with the times, too. The Netherlands, France and Australia have set up a few whole villages for people with dementia. The idea arrived in Canada in 2019 with British Columbia’s Village Langley, the first large-scale “roam free” dementia village. It allows residents to come and go as they like within the village, which features multi-coloured cottages with large windows, a living room, dining room, kitchen, family room and sunroom on a two-hectare secure setting. While people can move freely, perimeter fencing equipped with security cameras and sensors, mostly hidden by trees, combined with a Bluetooth-enabled security system lets staff know the whereabouts of residents at any time. The property features a community centre, a woodworking shop, a barn with chickens and goats, and vegetable beds tended by residents who can set their own times for waking, sleeping and meals. Despite the monthly price tag of about $8,000 to $10,000, it has a long waiting list.

Power can see the appeal. Much of the agitation present in people with dementia in nursing homes comes from hitting dead ends in a locked ward, he says. Restricting movement for people with dementia only heightens their sense of disempowerment. “There is no other population of people — outside of prisons — who are told they cannot live like the rest of us,” Power says.

In 2023, the Dutch government introduced legislation aimed at phasing out the use of locked wards and encouraging alternative solutions instead. These include enhanced personalized care, secure outdoor spaces and more training for staff to learn how to manage challenging behaviours in non- restrictive ways. Canada’s first public non-profit dementia village, Providence Living at The Views, opened in Comox B.C., last year with 13 hubs housing 156 residents, as well as a bistro, bar, art studio, grocery store and on-site daycare to foster intergenerational connection. Each household connects to a large secure interior courtyard so people can be outside. Residents set the rhythms of the day. Flexible routines allow them to have a drink at the bar, smoke in a designated area and enjoy intimate relations if they choose.

Experiments in autonomy are beginning to spread to traditional long-term care homes in Canada, too. At Village of Riverside Glen in Guelph, Ont., which is also a living classroom for health-care workers, residents are encouraged to live out their dreams, even if some of them might seem risky. “Never underestimate the capacity of people living with dementia,” says general manager Bryce McBain, who travelled with a delegation to the Netherlands to learn more about dementia- friendly initiatives. His facility is experimenting with technological tools such as an app that analyzes residents’ sleep patterns and movement, aiming to reduce falls and improve the quality of sleep. It is also trying out the concept of “errorless learning” to simplify life for people with dementia. For example, it offers just one essential utensil at mealtime rather than a variety of utensils that can cause confusion. “This sets them up for success because they are less likely to make mistakes and become frustrated,” he says.

McBain says “bubble wrapping” dementia residents and putting too much focus on liability risk limits the lives of people “who still have an adventurous spirit.” Staff at the home have helped residents with dementia — at their request — go ice skating, take a motorcycle ride or try ziplining, hot-air ballooning and even skydiving. One resident, Lillian Parker, fractured her ankle while skydiving and was in a cast for six weeks, says McBain. “She said the experience was incredible because she touched a cloud. And she said she wouldn’t hesitate to do it again,” he says. Ina Sven, a resident who lives with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, also jumped from a plane. Her daughter, Tessa Sven, shares a photo of her mother taken midair that captures her mother’s look of pure joy. “That was something I hadn’t seen in a while,” says Sven. “It gave her a real sense of freedom.”

Power says we need to stop thinking that people with dementia are victims and instead view dementia simply as “a shift in the way a person experiences the world.” He refers to the work of psychologist and Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl, author of Man’s Search for Meaning, who believed that the ability to find value in life, even in a life with great suffering, is essential to human survival. “If this is true, then helping those living with dementia to find and realize continued meaning in their lives is essential to their well-being and possibly their longevity as well.”

But not everyone is interested in that outcome. In 2020, the Netherlands was the first country to allow state-sanctioned euthanasia for those with dementia, if the person had requested the procedure while still mentally competent. Other countries, including Belgium, Luxembourg and Switzerland, followed.

Last fall, Quebec became the first province to allow advance requests for medical assistance in dying (MAID) to be administered months or even years in the future, when a person’s condition would leave them unable to consent to the procedure.

Sandra Demontigny, 45, a mother of three and a former midwife in Lévis, Que., became one of the first people on the Quebec waiting list. She was diagnosed with early-onset dementia at 39. She witnessed the agonizing descent of both her father and grandmother from Alzheimer’s and cannot abide the thought that she might have the same ending they did. “I don’t want my children to see me suffer the way I saw my father suffer. I will never be able to describe how bad it was,” she says, wiping away tears during a Zoom call. She says her father couldn’t walk and so he crawled, sometimes injuring himself.

“I know he would have wanted us to finish his life.” Her grandmother spent 10 years in a long-term care home. “She was just lying in bed not moving. People had to feed her. She couldn’t talk.” Demontigny, a spokesperson for the Quebec Association for the Right to Die with Dignity, wants to die on her own terms. “Like every mother, I love my children more than anything, but I don’t want them to see me like that — as a prisoner in my own body.”

The vast majority of Canadians — 84 percent, according to a 2023 Ipsos poll — support advance requests. But Power urges caution. “Many people I know who are living well with dementia were quite despondent at the time of diagnosis and didn’t realize at the onset that living well with dementia was a possibility. So I have reservations. The way medical professionals often position dementia from the standpoint of tragedy and loss simply adds to the notion that life after a diagnosis has no value.”

His own mother-in-law lived with dementia for seven years before dying at age 86. “She had a very unhappy life for many years before her diagnosis,” Power says. “But her years of living with Alzheimer’s — even though she forgot people and lived in long-term care — were some of her happiest.”

***

Anne Bokma is an author and journalist in Hamilton.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2025 issue with the title “Changing Our Minds About Dementia.”