Between classic Christmas films and the flood of new offerings each season, even the most casual consumers of holiday movies have an idea of what to expect. Perhaps it’s a scene featuring a gentle evening snowfall that leaves a perfect patch for snow angels or a cute moment made cuter by an overhead sprig of mistletoe.

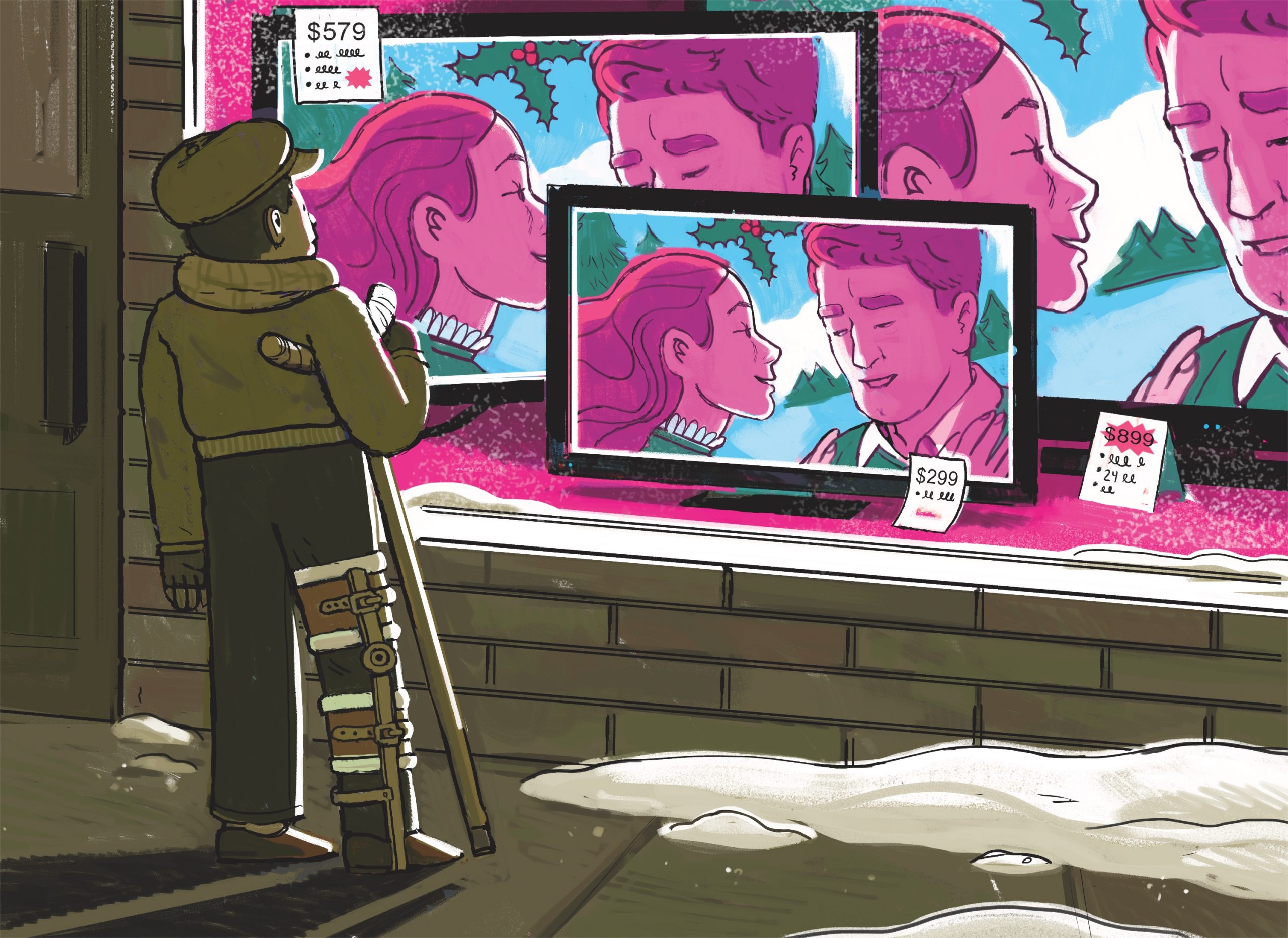

The thing about holiday movies is that they tend to feel familiar, even interchangeable. Consider the following examples. In one film, an ambitious career woman comes to a small town to rebrand its rustic resort. Instead, she falls for a handsome local and changes her hard-headed ways as she learns to appreciate the town’s charms and the true meaning of Christmas. Another film finds a plucky PR specialist who must team with a cantankerous (though still handsome) executive to run their company’s holiday charity events. Despite their initial differences, romance flourishes and seasonal cheer levels rise. Finally, there’s the film about a middle-aged man — depressed, desperate and facing financial ruin — who makes a drunken suicide attempt before being wracked with hallucinations of a world in which he never existed in the lives of his loved ones. Thankfully, he’s still handsome despite his troubles.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

If you recognized the first two examples, then you may be a connoisseur of the holiday movies the Hallmark Channel churns out by the dozens every year. (The two in question, If I Only Had Christmas and Let It Snow, also star genre staple Candace Cameron Bure and were made in Canada, Hollywood’s go-to destination for snowy weather, picturesque small towns and polite extras.) There’s always a life lesson to be learned, often about the need to put the solitary, selfish pursuit of worldly success aside and rediscover the homier values of family, community and romantic commitment. Whether the movies are more secular or overtly faith-forward in nature, they dress up the same mushy platitudes with the corniest of Christmas trappings.

As for the third example, perhaps you identified it as It’s a Wonderful Life — the 1946 seasonal favourite directed by Frank Capra and starring Jimmy Stewart. What’s striking is how much this classic tale deviates from the contemporary template for holiday fare. It may offer some of the same sentimental pleasures, but it also has a harder edge as it acknowledges life challenges that may not be so easily resolved with one magical Christmas. While Hallmark and its imitators have had enormous success with a formula that millions of viewers find as cozy as a reindeer-patterned sweater, their offerings risk crowding out this other kind of holiday movie, one that may be more resonant because its tidings of comfort and joy are grounded in a less rosy-cheeked reality.

The creators of some of the most cherished Christmas stories certainly knew this to be the case. Indeed, Charles Dickens’ original 1843 novella A Christmas Carol would seem like a bitter-tasting concoction of cruelty, misery and misanthropy, even if the author hadn’t killed off Tiny Tim (albeit temporarily). The 1951 film version starring Alastair Sim may come closest to capturing the book’s sometimes grim nature and portrayal of Victorian-era deprivation. That’s also why it remains the most satisfying of the many screen adaptations, with Ebenezer Scrooge’s change of heart being more affecting because of his coldness throughout much of the story. Unlike the comfortably well-off characters who dominate Hallmark’s output and similar holiday rom-coms like Love Actually and The Holiday, the people around Scrooge experience inequities and hardships that feel truer to real-life struggles.

The displays of generosity and self-sacrifice in such stories have more force because the characters have so little to give. To cite another seasonal chestnut, The Gift of the Magi — O. Henry’s much-imitated story about a newlywed couple who go to great lengths to give each other meaningful Christmas presents — would have little of its poignancy if they could afford to buy one another spa gift cards.

More on Broadview:

- What I listen to instead of Christmas music

- I didn’t know what Christmas meant until one special service

- My grandma was a Grinch at Christmas, but I wouldn’t have it any other way

This gap between what the holiday movie used to be and what it has become is further highlighted by another new Christmas-themed film, which debuted at Cannes in May and arrives on Disney+ later this year. The project came about when the celebrated writer-director Alfonso Cuarón (Roma, Gravity) reached out to the Italian filmmaker Alice Rohrwacher to offer her the chance to make the kind of Christmas tale that harkened back to the style and sensibility of an earlier era.

The result is Le Pupille, a delightful 40-minute short set at a Catholic boarding school in Italy during the Second World War. Under the watchful eye of the nuns in charge, a gaggle of girls perform the season’s duties and rituals, including their roles in the annual pageant that generates much of the school’s meagre funding. When one of the youngest is castigated for an apparent misdeed, she is tormented by worries that she’s become a “bad girl” who deserves no sort of kindness at all. More consternation is caused by the arrival of a cake that is almost surreally decadent under such Dickensian circumstances.

An homage to both the comedies of Charlie Chaplin and the bleak but humane films of postwar Italy, Rohrwacher’s short is whimsical and weighty in equal measure. There’s no disguising the challenges the girls endure as they listen to a radio broadcast of war propaganda or enviously watch the departure of the one girl who’s able to spend the holiday with family. Whether they’re orphaned or unwanted, at least they have each other. They also have a Mother Superior — played by Alba Rohrwacher, the director’s older sister and the star of her equally engaging features The Wonders and Happy as Lazzaro — who struggles with her own stern ways and longs for some softness in her life too. Like so many great Christmas stories, it’s a thoughtful rumination on the true meaning of generosity and how far we’ll go to be “good” at the time of year when it seems to count the most.

The heavier themes of Le Pupille are a welcome antidote to the sentimental sweetness that overwhelms our screens this time of year. Of course, there’s room for both kinds of holiday movies. After all, it can feel just as good to gorge on Hallmark’s sappy fantasies as it would for the girls to feast on that eye-popping cake.

***

Jason Anderson is a writer, critic and film programmer in Toronto.

This essay first appeared in Broadview’s December 2022 issue with the title “Christmas without the schmaltz.”