“I remember crying myself to sleep a lot of times, wondering why people would [hate] people who looked a little different,” reflects former National Hockey League (NHL) coach Ted Nolan. It’s October 2021, and he’s speaking to nine Indigenous teenage boys about the racism he experienced playing Canada’s official winter sport.

The group is gathered in the cavernous Scotiabank Pond arena in North York, Ont., for a day of high-performance training and words of inspiration from hockey’s elite. Some of these players have travelled from as far as Quebec to attend the inaugural Indigenous Mentorship Summit. The event is co-hosted by Nolan’s organization, 3NOLANS (named after him and his sons), and Hockey Equality, a registered Canadian charity dedicated to creating diversity and inclusion at all levels of hockey.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Nolan is from Garden River First Nation, also known as Ketegaunseebee, and played minor hockey in Ontario, eventually earning spots on the Detroit Red Wings and Pittsburgh Penguins. Later, he coached the Buffalo Sabres, becoming in 1995 the first full-time Indigenous head coach in the NHL (prior to that, George Armstrong, of Algonquin-Irish heritage, served as interim head coach for the Maple Leafs during the 1988-89 season). At first glance, Nolan’s story sounds like every young player’s dream: working his way to the pros through sheer grit and talent. But in his 12-minute speech during the summit, Nolan details how difficult his journey was.

One particular year stands out for him, when he left his community to play for the nearby Kenora Thistles during the 1975-76 season. He was subjected to countless racial slurs from opponents and teammates and was told to go back to the reserve. It took a toll.

“There was another First Nations guy on the team…and we came back from a game one time, and he said that’s enough for him, he couldn’t put up with it no more,” says Nolan. “My two brothers came into town and tried to bring me home because they knew how tough it was, but for whatever reason, I said, ‘No, I want to stay.’”

Nolan persevered, but hockey culture largely hasn’t changed for players who are Black, Indigenous or people of colour (BIPOC). As media reports can attest, discrimination persists across all levels of the sport. This issue was thrown into the spotlight in 2019 when Hockey Night in Canada commentator Don Cherry made racist comments about immigrants. Sportsnet fired Cherry, but the incident reinvigorated a national conversation about racism in hockey.

While hockey’s owners and managers have been criticized for not doing enough to make the sport inclusive, some high-profile members of the hockey community are finding solutions. This includes Nolan. “I just think, hockey or any other positions in life, shouldn’t be different standards for different people,” he says. “If a First Nations kid walks in late to a practice one time because he doesn’t have a car…don’t bench him from the practice and call him lazy. If you do that, then you gotta make sure you do that to everybody.”

Hockey Canada is the national governing body for the sport, overseeing all programs from entry level to high performance. According to its 2019-20 annual report, “Hockey is Canada and Canada is hockey,” and the numbers indicate the organization isn’t wrong. That year, over 605,000 players age five and up were involved in hockey across the country (the numbers have since fallen due to COVID-19).

But who are these players? And which Canada are they talking about? If you look at team photos, the sport has long been dominated by those who are white and male. While girls are increasingly playing, we don’t know how many players overall are BIPOC. Hockey Canada told TSN in 2020 that it would begin collecting data on racialized participation as early as the 2021-22 season, but it did not confirm by press time whether this had indeed started. However, if NHL rosters are any indication, with just 5.7 percent players of colour according to Hockey Equality, the results will be low.

People of colour and Indigenous persons make up more than 27 percent of Canada’s population, which means they are sorely under-represented in our national sport. As Nolan and his teammate experienced, a lack of diversity contributes to hockey’s embedded racial biases and class barriers, which can dissuade non-white people from participating, creating a vicious cycle that persists to this day.

During a high school game last October, for example, 16-year-old Keagan Gaywish, from Rolling River First Nation in Manitoba, encountered racial taunts from opposing fans. When Gaywish was in the penalty box, a fan also pantomimed beating a hand drum, a custom that belongs to First Nations people. “It made me feel like I wanted to quit hockey, like, I’m not going to, but it just made me want to stop playing,” Gaywish told CBC News.

Just weeks later, Mark Connors was in the media. The 16-year-old goalie from Halifax said he was called the N-word repeatedly by spectators during a tournament in Charlottetown. Later in the hotel, players from an opposing team told him that hockey was a “white man’s sport.” In a February ruling, Hockey PEI’s disciplinary committee suspended five minor hockey players from the Island for 25 games.

Experts view Hockey Canada and its provincial branches, like Hockey PEI, as key to addressing incidents of racism. Following a 2019 roundtable discussion at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., a group of scholars and writers who have studied and in some cases experienced racism in the sport co-authored the “Policy Paper for Anti-Racism in Canadian Hockey,” which has already become the seminal framework for anti-racism initiatives.

The paper lists 10 substantive calls to action — eight of which are expressly directed at Hockey Canada. They include the governing body instituting a duty to internally report and track all incidents of racism. This policy was put into effect for the 2021-22 season when Hockey Canada updated its rulebook to finally include discrimination and racism under “Section 11: Maltreatment.” Now, any players or team officials who engage in discriminatory behaviour will receive a gross misconduct penalty, and refs must fill out a detailed game report of what occurred.

While this is a start, a lot more work needs to be done at all levels of the sport. “It’s education, policy and programming. It is how you hire people. How you hold people accountable when issues do come up,” says Courtney Szto, a Queen’s kinesiology professor who helped author the policy paper. “I think what hockey has yet to really understand is how long it takes for this kind of work to take hold. It has to be day-in and day-out, and incorporated into everything that you do.”

The paper also outlines intersectional components tied to racism that have contributed to hockey being less accessible for racialized groups. This includes the increasing unaffordability of the game — a problem not unique to BIPOC communities but definitely a barrier.

A 2019 survey of over 1,000 hockey parents across North America found that nearly 60 percent spend more than $5,000 per year to keep their children on the ice. Their costs include league fees, equipment, travel and camps. To afford the sport, many are reducing other household expenses like food and entertainment, and some are taking on debt or getting second jobs.

The prohibitive costs of hockey are staggering at all levels, especially when players progress into AAA minor hockey, the most competitive of the minor hockey tiers. For a closer look at what it takes to become a player in the Ontario Hockey League (OHL), which recruits AAA athletes and can be a launching pad to the NHL, the Hamilton Spectator conducted a survey in 2016, obtaining the postal codes of 218 OHL players and cross-referencing the data with Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey. The results were startling.

Eighty percent lived in neighbourhoods that exceeded the provincial median family income of $80,987, and 66 percent came from areas that exceeded the median home value of $300,862. The numbers reveal a fundamental truth about the elite development model of Canadian hockey: to make it professionally, you often need to be from an affluent community or receive significant subsidization.

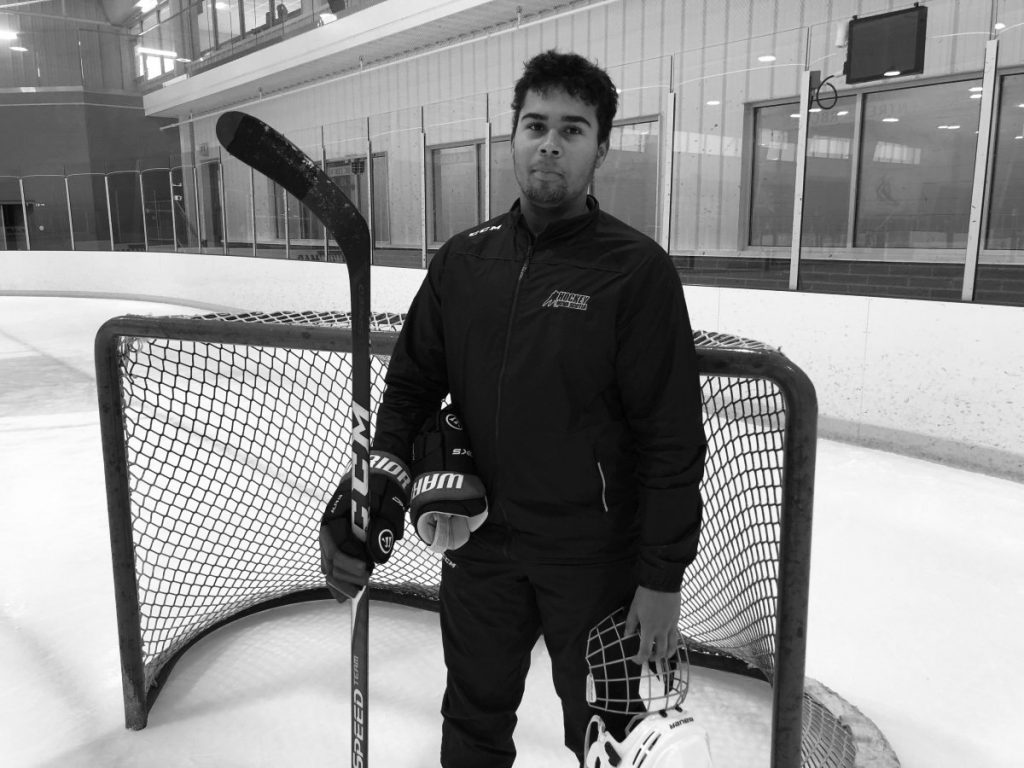

One organization exploring alternative models to traditional pathways is Hockey Equality. Founded by former NHL player Anthony Stewart, the charity highlights the prohibitively expensive costs of equipment, registration and ice time as major reasons why BIPOC players have been under-represented at professional levels. Hockey Equality is hosting a series of mentorship events like the Indigenous Hockey Summit to try to increase participation from underrepresented groups.

Raised in Scarborough, Ont., Stewart played over 260 games in the NHL with the Florida Panthers, Atlanta Thrashers and Carolina Hurricanes before retiring from professional hockey in 2016. He now works as an on-air analyst for Sportsnet. As a teenager, he was a standout player in the Greater Toronto Hockey League and one of the lone Black players at the AAA level. Stewart says he was only able to play at the AAA tier because his costs were subsidized by other parents on his team.

“I think what hockey has yet to really understand is how long it takes for this kind of work to take hold. It has to be day-in and day-out, and incorporated into everything that you do.”

Queen’s University’s Courtney Szto

Through Hockey Equality, Stewart wants to help young BIPOC players understand that there is more than one way to make it professionally. “People think…if I’m not elite at nine years old… there’s no opportunity to make it,” says Stewart. “There are different paths. And it’s a lot more than just being a good hockey player. We’re trying to teach [future generations] to be a good person, be on time, be punctual, have a sense of pride [and] don’t change who you are.”

A Black NHL player who took a different path is Toronto Maple Leafs forward Wayne Simmonds. At Hockey Equality events, he explains to the kids that he never played AAA minor hockey as a young teen. While others in his age cohort moved on to junior leagues or the OHL, his turn didn’t come until age 18, when he made it onto the OHL’s Owen Sound Attack (in the OHL, the teams incur the equipment and playing costs). Other NHL players skipped AAA and played university hockey instead. The lesson here is that you don’t necessarily have to take the most expensive road to succeed.

Stewart also says more stories of racialized players need to be told. He cites Toronto Marlies’ forward Josh Ho-Sang, who was having an excellent season in 2021 and recently played for Team Canada at the Beijing Olympics. Stewart says he spotted Ho-Sang’s talent six months before the media did. He’d like to see the sports press “going above and beyond to try to tell these stories.”

Representation in the press and on the ice certainly matters. Being one of the only BIPOC hockey players can be hauntingly isolating. Akim Aliu was the sole Black player on the Windsor Spitfires when he made national headlines mere weeks into his OHL career in 2005. His teammate Steve Downie relentlessly made fun of Aliu’s accent and skin colour. When Downie lodged a stick into Aliu’s mouth during practice, Aliu had had enough and fought back. A video of the fight made its way across the country.

Aliu was suspended one game, while Downie received a five-game sanction. But their careers took very different paths from there. A few months later, Downie was viewed as a hero in some circles due to his contributions to the Canadian national men’s junior hockey team. Aliu, on the other hand, believed he was subject to character assassination at every step of his OHL career. For example, NHL Central Scouting — a league department responsible for assessing every draft-eligible player — gave Aliu top ratings for his shot and physical strength but marked him lower on traits like discipline and work ethic.

Aliu didn’t speak publicly about how his professional career had unfolded until he issued a statement to Sportsnet three years ago. “I strongly believe the publicity around the hazing incident in Windsor turned my career sideways and to this day I’ve never been able to reclaim my reputation. I was humiliated as a target of hazing and then physically assaulted and yet somehow people looked at me as a villain and troublemaker.…I tried to do my part to break the cycle of cruelty towards young, vulnerable kids. And that’s why I’m speaking up again now.”

In November 2019, Aliu went public again, this time on Twitter. He called out Bill Peters, former head coach of the Rockford IceHogs, for racial abuse when Aliu played for the team. He shared that Peters used the N-word toward him because of the hip-hop music he played in the locker room. The allegations took the hockey world by storm, and Peters, who admitted to the racial slur but said it wasn’t directed at anyone in particular, was forced to resign from his post as head coach of the Calgary Flames.

In speaking out, Aliu found his voice as a leading anti-racism advocate. He co-founded the Hockey Diversity Alliance, a group of current and former NHL players dedicated to eradicating racism from hockey. “This is just the beginning,” Aliu told TSN in November 2020. “This is the first time in the history of our game in over 100 years that people actually want to have this conversation, and it’s a conversation that can be had in the open.”

That same year, Aliu started the Time to Dream Foundation to make sports, including hockey, more inclusive, affordable and accessible for youth. Joining him on this mission was one of his minor hockey teammates, Aaron Atwell, who assisted Aliu in coaching a new BIPOC youth team in Toronto. “Representation is huge,” says Atwell. “I know my nephews — they’re 12 and six — don’t play hockey, but when they heard that there was a hockey team full of a bunch of BIPOC athletes around their age, they wanted to go watch.”

Aliu and Atwell are both acutely aware of the importance of being involved in organized sports. “Akim and I grew up in rough neighbourhoods. A lot of the kids that we grew up around ended up in juvie, in jail, with drugs, not going to school,” says Atwell. “The fact that I’ve had sport to keep me occupied…it’s life-altering. At the end of the day, sport is sport, but it opens up doors for life.”

This is why Atwell wants to help eradicate racism from the sport he loves. “If there’s more light shed on this, hopefully that will push people to want to make change, or to have to change. In turn, it will help these kids, so they can get more involved and have more options than what they do now.”

After Ted Nolan concludes his speech at the Indigenous Mentorship Summit, a number of teenagers patiently wait to speak to him. Standing beside him is his son Brandon, who used to play for the Carolina Hurricanes. Father and son pose for photos and answer the kids’ questions. It’s obvious that they take their roles as mentors seriously. Even though racism remains entrenched in the culture of hockey, the two have hope for change.

“Nowadays, you get a lot more support from community members in regard to racist issues,” says Brandon. “We’re seeing a lot more people speak out about it, which is always good. The more awareness we can create, hopefully we can break down racism and systemic racism throughout sports.”

***

Arun Srinivasan is a Toronto writer. His book about the history of racism in hockey is expected to be released in 2023. This story first appeared in Broadview’s April/May 2022 issue with the title ”The good fight.”