A note from the author: What a difference a season makes! When I first drafted this article in late winter, I had no idea that as it went to press in the spring, we would be facing a global pandemic. I worried the story of a disabled senior being out and about on her scooter would contrast too sharply with the loss and isolation we’re now experiencing. Given the increased health risks I face, I have not been out on my scooter since early March. But I decided to go ahead with this article because when there’s talk of medical care for seniors and disabled people being rationed to save younger, non-disabled lives, it is even more important that our voices be heard. When this is finally over, it will be time to consciously choose and build accessibility for all.

___________________________________________________________________________

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

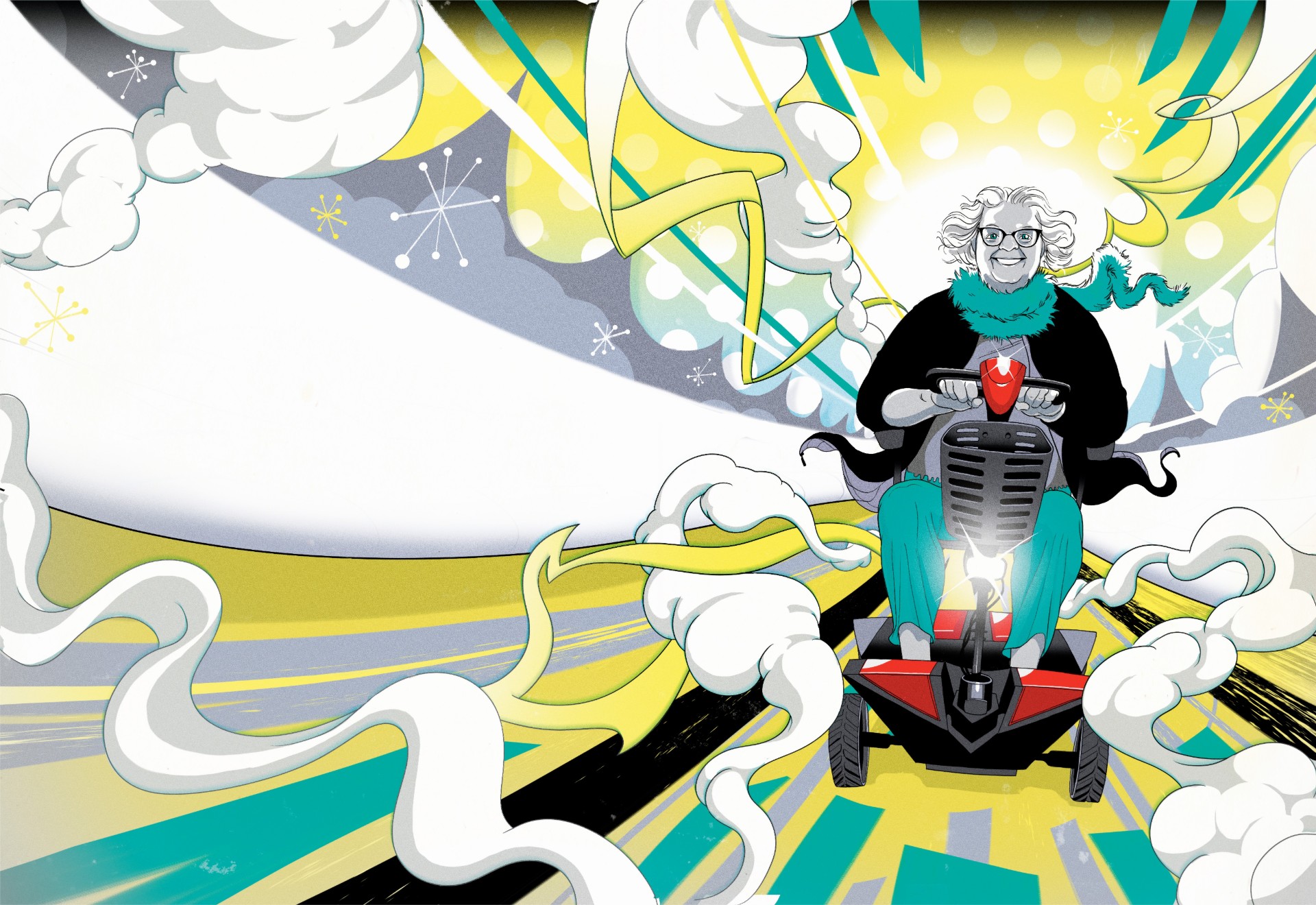

In June 2019, two landmark events occurred that I never expected to see in my lifetime. Canada passed Bill C-81, the Accessible Canada Act, and I became the proud owner of a sporty new candy-apple red ride: my mobility scooter.

I’ve named her Rosie the Riveting.

Rosie earns her name every day for all kinds of intersecting reasons. People really do find her riveting. Pedestrians young and old, from all walks of life, stare at her non-stop. One glance at Rosie barrelling full steam down the sidewalk, and many start to smile. Others try to nail me in place with all kinds of negative assumptions and stereotypes about a fat old woman who needs a scooter. But my new life with Rosie doesn’t depend on what others think of her. I know beyond all doubt that she has enriched my disabled life and given me a deeper understanding of how social justice for disabled people is intrinsically linked to our ability to move through the world.

More on Broadview: What not to say to the parent of a child with a disability

Rosie is riveting to me because she newly fastens me to planet Earth. For the first time in my life, I travel confidently on the land, not in fear of it. Rosie reattaches me to my neighbours in ways I thought I had lost forever. She makes it possible to get out into my community, to make and build connections. Further, Rosie rivets each day of my life to new purpose. My long-standing activism for accessibility is now bolted to an understanding of how to face and fight four kinds of barriers listed in our new Accessible Canada Act. This legislation is the first federal accessibility legislation in Canada. It applies only to areas under federal jurisdiction but will likely set a template for standardizing accessibility to break down these four barriers: physical, architectural, technological and attitudinal.

Physical barriers

Like 22 percent of Canadians, I’m disabled. At 65, like three-quarters of disabled Canadian seniors, I have more than one disability.

I was born with congenital anomalies, once called birth defects, in both my feet. My disability is degenerative. In my 50s, I used a crutch. In my 60s, I got a walker. Today, I also have panic attacks, periodic depression, heart disease and a creeping whole-body arthritis. Despite surgery and medication, I’m in constant pain. I can walk only a block, only with my walker. I fall far too often, knowing each fall might end my mobility and, should I break a hip, possibly my life.

Pre-Rosie, exhausted by pain and fear, I was increasingly using a transport wheelchair, an old-school non-motorized chair that must be pushed by someone else. Being carried from place to place like Cleopatra wasn’t the worst way to travel.

When I got Rosie in the spring of 2019, she refocused and re-energized my life.

I went from spending depressing days alone inside to spending whole days outside. Rosie zips along faster than your average pedestrian, and her rechargeable battery lasts for 17 kilometres. At first, I was terrified. I have zero balance. Every little dip and lilt registered in my brain as falling, as me about to be ejected like Batman from the Batmobile. To the delight of many passersby, when I hit even a tiny slant in the sidewalk, I screamed. It took a month before I relaxed and learned to trust that Rosie is far more athletic than I’ve ever been.

Today, we see it as discriminatory, as social justice denied, when disabled people are banned from inaccessible buildings. But in summer 2019, I realized it is equally discriminatory when disabled people cannot get outside to enjoy nature and their neighbourhoods.

On my first trip out with Rosie, she took me down the hill from my apartment to the Burlington, Ont., waterfront. We drove right to the water’s edge, a place I had only been able to gaze at longingly from my car. Once I rigged Rosie up with a front and rear backpack, I could pull right up over the grass to the picnic tables and enjoy my lunch. Until I got the outdoors back, I did not realize how very much I had missed it. I’d gone so long without a day’s sun on my face, so long without a lakeside breeze, that I had stopped grieving nature, given up and put the loss from my mind. With Rosie, I rediscovered all kinds of outside fun. I rode her right onto the GO train and spent a lovely day at the Canadian National Exhibition.

But Rosie gives me more than new destinations. I see the physical barriers of the land itself differently. I’ve become a terrain expert, training myself to avoid cracked, uneven sidewalks and the artsy brickwork sidewalks of the main street. Rosie teaches me this: access that is not flat and smooth is not access. Bouncing over sidewalk cracks hurts every joint in my arthritic body and churns my picnic lunch into a milkshake in my stomach. I must set a path by the flattest curb cuts, avoiding the old humped curbs that hurt like Hades when hit.

I thought I was being careful, but after only three months, Rosie’s axle broke. I hadn’t smashed into a wall or a pothole. The repair person said it was common, the cumulative effect of hitting raised curbs, uneven sidewalks and elevations in doorways. Thankfully, Rosie remained under warranty, or the fix would have cost $900. From that day on, I used the road wherever possible. If Rosie broke again, I could never afford her repair bill. Like many disabled people, I live on the poverty line.

Taking Rosie right onto the road is less jarring, but also less safe. Some drivers roll down their windows to scold me, to insist I belong on the sidewalk. Come winter, given poorly shovelled sidewalks, I have to use the road or remain housebound. At crosswalks, I must inch carefully around mounds of snow because too many drivers like to endanger my life by playing Race the Cripple.

Is getting outside onto the land and into the world worth the risk? Yes, but it shouldn’t have to be so dangerous. In a just society, sidewalks would be shovelled and repaired, curbs would be brought up to code, and seeing Rosie and I out and about would be so common that no one would stare.

Architectural barriers

Before I got Rosie, I couldn’t go into any building that had even one front step or inside stairs. Plainly put, that’s most buildings I encounter. After being kept out for so long, I made the decision that now that I could get to buildings, I was going to go into them. I wasn’t going to ask permission. I’d assume it was my right to be there.

Rosie and I got into buildings I hadn’t been able to access independently in over a decade: the grocery store, the mall, the movies. I met people in my neighbourhood for the first time: everyone from coffee baristas to librarians to folks at my seniors’ centre. I took Rosie to breakfast, lunch and dinner, to the bank and local swimming pool, and underwear shopping at Walmart.

My new life with Rosie doesn’t depend on what others think of her. I know beyond all doubt that she has enriched my disabled life.

In fall 2019, I rode Rosie into my polling station and straight into the voting booth. In winter 2020, when teachers were on strike, as a former picket captain for the Ontario Secondary School Teachers’ Federation, I rode Rosie into Tim Hortons to buy Timbits then rode right up to the line to offer sweet solidarity to my colleagues.

But increased access is not equal access. Some shop and restaurant owners have asked me to leave. Or asked me not to come back. They claim I’m a barrier. I’m in the way. When I point out that their establishment should have aisles wide enough to accommodate a wheelchair, they shrug. They want me to be the problem that goes away. They don’t want to see their inaccessibility as their problem.

Even with Rosie, I’m still banned from some two-thirds of downtown buildings because they have a front step. Even when an entrance is flat or has a ramp, few have automatic doors. This means I have to wait. Like a little child, I have to ask a big, strong abled adult to please let me in. When I get in, sometimes there isn’t clearance space to turn around, and I have to embarrass myself by backing right back out.

When will this change? The new Accessible Canada Act applies only to government buildings. Under the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act, Ontario is supposed to be barrier-free by 2025. Unfortunately, the act doesn’t have much teeth in practice. Whenever I ask local businesses if they are going to meet this accessibility deadline, they squint like budgies and say the same thing: “What deadline?”

Technological barriers

Full and equitable access to technology means everything from captioning videos and podcasts to providing online information that can be read aloud by screen-reading apps. Access to technology for a person prescribed a mobility device would be just as full and equitable.

At least, that’s what I naively assumed would be in place before I got Rosie. It never occurred to me that the system’s failure to use updated technology and the built-in delay that caused would be weaponized against me.

In December 2018, my doctor recommended a scooter to get around outside, but she wanted me to keep using my walker inside my apartment for as long as possible. I didn’t yet need a power chair. She sent my name to an occupational therapist registered with the Ontario Ministry of Health’s Assistive Devices Program (ADP), which funds mobility devices, and told me to expect a phone call. When I checked ADP’s website, I was shocked by the number of devices ADP does not cover, but they do cover scooters.

Six weeks later, in mid-February, a junior occupational therapist phoned me. She visited me another six weeks later at the end of March. She spoke to me as if I were a child, using overly simplistic language and a patronizing tone. I explained that I was a high school English and drama teacher who had done her homework: I’d attended the Abilities Expo in Toronto, test driven every scooter at that trade show and done hours of online research. I still had to ask her to please use adult vocabulary. Twice.

To all my questions, she chanted the same answer: “I’m only a junior OT. I’m not ADP certified. I have no idea what does or doesn’t qualify for ADP. That’s entirely up to my boss, the senior OT.”

I had to answer her questions with no information as to what might or might not qualify me. She left saying only that she would call me. A month later, at the end of April, she phoned me to say the senior OT hadn’t looked at my application yet and was about to go on holiday for three weeks.

She then said I had to be assessed for a specific model of scooter, which she failed to tell me when we met. I have a driver’s licence and still drive my car, but she told me to book a test drive at a scooter store, now booking three months later, in July, so the senior OT could come out and watch me to ensure I could drive a scooter safely. Yet again, she said she didn’t know anything about what models would or wouldn’t qualify for funding. She said the senior OT would not tell me anything on the spot, and instead would send a private recommendation to ADP, which would then take another three to five months to reply. Then, and only then, would I find out if I qualified to receive up to 75 percent of the cost — or no funding at all. Although her explanation did not match written policy procedure as described in the ADP manual, I was left with no choice but to take her advice.

Another month later, on May 21, the junior OT phoned to tell me the July date I’d supplied was not acceptable because the senior OT was now fully booked until September. She added what I wish she had told me at our first meeting: that since my walker, which was ADP covered at 75 percent, wasn’t five years old, I would likely get considerably less than 75 percent coverage for another device. I might even get nothing. She emphasized that I had to “prove a drastic change in mobility” to qualify for any new device within a five-year term but wouldn’t tell me what qualified as a “drastic change.”

In other words, a full year from when I started this process, I would find out if I qualified.

The junior OT cheerfully added that if I didn’t qualify on one scooter model, I could begin the process afresh and presumably wait up to another year. She encouraged me to rent a scooter in the interim. It is no surprise that rental companies benefit from ADP delays. If I were to rent then buy a scooter, my store would deduct the first month’s rental from the price. If I had rented a scooter for the year as I waited to hear if I qualified, it would have cost me $2,200 on top of what I would owe for the scooter. If all this information had been easily accessible, I could have made an informed decision on the very day in December 2018 that my doctor recommended a scooter.

I ended that May 21 phone call believing that this whole process is deliberately designed to delay and discourage people from applying for ADP. Drag it out until people give up. Make people give up.

I gave up. I hung up the phone and went online. The scooter I wanted was Canadian, made in Beamsville, Ont., a mere half-hour from my home. At my local scooter store, it cost $3,000. Twenty minutes later, I maxed out my credit card and bought the very same scooter on Amazon for $1,800. Three days later, on May 24, my Canadian-made scooter was shipped to me, for free, from Florida.

Whenever I look at Rosie, I still see red, in more ways than one. Technology provides the solution to make this whole process far more accessible and equitable. It would save everyone time and money if there was a clear and easy-to-use government website and a simple, digitally trackable approval process that leads to timely funding. It is sadly ironic and personally unacceptable to me that a government program designed to assist disabled people with accessibility devices instead remains inaccessible.

Attitudinal barriers

While Rosie is always riveting, the reactions she gets aren’t always kind or friendly. I do my best to avoid the stares of pity and disgust. It’s impossible to avoid those who refuse to share the sidewalk. After years as a drama teacher, I know an improvised power play when I see one. In repeated sidewalk faceoffs, the strangers who have elected to be my scene partners aim straight at me with a smirk, hoping to make me swerve around them, even though I’d have to drive right off the curb. I used to stop; now I keep going. I enjoy the shock on their faces when they realize they have to move if they don’t want Rosie to kiss their kneecaps.

I also enjoy it when pedestrians race me to get through an intersection, and I beat them to it. I do not enjoy it when drivers race me at stoplights, or when they fly around a right turn even though I’ve got a walk light. I’ve been sworn at, given multiple fingers, told to stop faking it, to get off my fat bottom and to take my ugly, broken body back inside and stay there.

Sometimes, it’s people who think they’re being kind who do the most harm. “Are you always so floral?” A woman with a jaunty ponytail and a huge smile asked me this on a summer day when I was wearing a black-and-white floral print top. In her mind, she wasn’t being rude or intrusive. Quite the contrary, she felt entitled to put her hand on Rosie and stop us dead because she intended to be kind. “I’m asking because it’s so nice to see someone like you out and about. Especially someone so fashionably dressed and with a smile on her face. Good for you, dear!”

I wanted to ask her if this meant she usually saw people like me out and about in rags, or perhaps stark naked, storming about with murderous rage on our faces. I did not. Instead, I said, “Someone like me? What does that mean?”

I used to stop; now I keep going. I enjoy the shock on their faces when they realize they have to move if they don’t want Rosie to kiss their kneecaps.

Her face fell. I wasn’t following the script in her head. I was supposed to say thank you, make her feel good about herself for being kind to me, then let her move on. I was absolutely not supposed to challenge her assumptions about me being a sweet little old crippled lady.

She frowned. “Well, you know, dear, somebody old like you. Who can’t walk. But who doesn’t let that little problem get them down.”

“It’s a huge problem. It gets me down all the time. Especially right now.” That was the answer in my head, but I didn’t say it aloud. I did aim straight at her and flip Rosie’s switch to run at full throttle. I’ve decided that there is only one correct social justice response to all barriers physical, architectural, technological and attitudinal.

“Excuse me,” I say. “Please get out of the way. This space is mine.”

The claiming of space is always about more than sidewalks. It’s about the right of seniors and disabled people, of all marginalized people, to live in the world with our human rights equally seen, valued and protected. This spring, even as Rosie sits unused during self-isolation, the promise she represents of an equitable world still rivets me to hope. My little red scooter-in-waiting is still fully powered with my belief in accessible social justice and our capacity to build collective change.

Dorothy Ellen Palmer is a writer and disabilities activist in Toronto.

___________________________________________________________________________

I hope you found this article from Broadview engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher

Fantastic! You hit the nail right on the head. A comprehensive view of life with a mobility device.

I rest my case.