In a Nova Scotia classroom, educator Morris “Moe” Green invites a dozen pubescent boys to draw their chairs into a circle. He helps them relax with a silly icebreaker question — like “If you could speak an animal language, what language would it be?” — and then gets down to business. Green’s program is called Guys Work. Aimed at boys in grades 7 and 9 in Nova Scotia, it covers topics such as sexual coercion, power dynamics in intimate-partner relationships, pornography and gender-based violence. Through information sharing, discussion and group exercises, Green encourages self-reflection and vulnerability, but also finds ways to get the boys “to step in their own bulls–t.” On the floor, in the centre of the circle, are two areas marked “Okay” and “Not Okay.” Green asks the boys whether they think, when they become parents, they’ll be strict or more lenient. Once that seed is planted, he gives each boy a stack of cards on which consensual intimate acts are written — everything from holding hands to taking a shower together or intercourse with a condom. The boys are asked to imagine that they’re the father of a 15-year-old son and determine which of the acts they would allow him to engage in. Almost everything ends up in the “Okay” pile — often, Green notes, to an excitable chorus of “Oh yeah!” and “That’s my boy!” Then, Green suggests a change: the boys must now envision being the father of a 15-year-old girl. Instantly, the mood shifts. “They’ll go, ‘Whoa!’” says Green, and some start squirming in their chairs. “A kid will typically just kick the entire pile over to the ‘Not Okay’ area, and I’ll often go, ‘What the f— just happened?’”

It’s often a funny moment, Green says, because the boys are immediately aware of the difference. They’ll start explaining that they want to protect their daughter but are quickly confounded by how to reconcile that with the idea of raising a son to be a player.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

For Green, this is the perfect segue into his ultimate message: “If we want to protect the girls in our lives, maybe we need to think about how we’re raising our sons,” he tells them.

On social media, at #MeToo rallies and in their daily interactions, girls and young women are increasingly speaking out on a range of issues related to gender-based violence and consent. But experts say that boys and young men still lack the tools, knowledge and empathy to act as genuine partners in the fight for gender equity. According to a 2017 U.S. survey by Making Caring Common, a project of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, a large majority of 18- to 25-year-olds have never had a conversation with their parents about consent, and never heard from them that they should not have sex with someone too intoxicated to consent. While 87 percent of women surveyed reported having experienced some form of sexual harassment, 76 percent of men reported that they had never had a conversation with their parents about how to avoid sexually harassing others, and most had never had a conversation about misogyny. And about one in three male respondents believed that men should be dominant in romantic relationships.

While the results are worrying for women, these norms are also bad for boys, keeping them trapped in a “man box” — discouraged from expressing vulnerability and empathy, from asking for help and from developing a sense of what healthy relationships look like, according to Peggy Orenstein, author of Boys & Sex: Young Men on Hookups, Love, Porn, Consent, and Navigating the New Masculinity.

Many gender-based violence researchers and Canadian NGOs believe interventions for adults who perpetuate violence come too late — after the harm has been done. They are now calling on local and provincial governments to offer more programs for middle and high school students designed to help promote healthier ideas about masculinity and gender equity. Increasingly, the question is not simply if we can stop domestic violence but something broader: can we reimagine what it means to be a man?

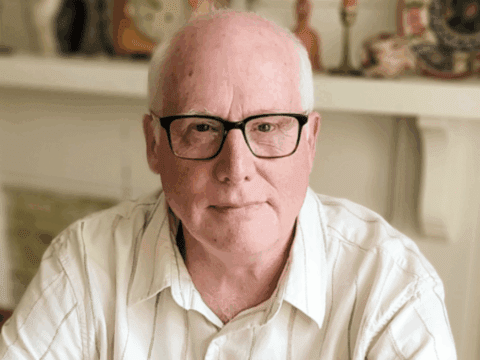

Moe Green retired from Nova Scotia’s Department of Health and Wellness a few years ago, and his last government job was to support a network of youth health centres across the province that were staffed by public health nurses. Early on, they realized that boys simply weren’t using the resource as much as girls. “Part of that script of masculinity says that if guys have problems, they should keep it to themselves,” he says from his home in Halifax.

And so Green started Guys Work, a program for boys in grades 7 and 9. The Grade 9 program is running in about 20 sites across the province, and the Grade 7 program will soon be running in five of the province’s regional centres for education (similar to school boards). In the previous school year, Green estimates that 150 school-based staff were trained by Guys Work. The program typically spans eight to 12 sessions, which are mandatory, and has received support from a mix of government, academic and non-profit sources.

One of Green’s core mandates has been to normalize seeking help. “There are definitely societal pressures to suck it up — the ‘boys don’t cry’ kind of thing,” says Lachlan Brown, a 16-year-old student at Dartmouth High School who attended Guys Work sessions when he was in Grade 9. By the end of Green’s pilot version of Guys Work in 2012, 20 percent of the participating boys stepped forward and asked for help with something.

Green, who likes to tell rich anecdotes to make a point, recalls that not too long ago, a teenage boy walked into the principal’s office at his high school and announced that he planned to kill himself. The boy was admitted to hospital, staying for a month while being treated for depression. But not long after his first assessment, the boy’s psychiatrist had a question for the principal, who later relayed it to Green: “The psychiatrist was like, ‘What’s “guys’ group”? Because he says that’s why he’s here,’” recounts Green, adding that the boy also told his psychiatrist “he learned that it isn’t a sign of weakness to ask for help.”

The inability to reach out for help has been tied to the flailing rage that drives gender-based violence, according to some experts. That rage can also lead to deep anguish: in Canada, men’s suicide rates are three times higher than women’s. “We know that, by the age of 15 or 16, boys are reporting having fewer close friends, having fewer people to talk to and fewer people to be vulnerable with,” says Roseline Carter, director of programs for Calgary’s WiseGuyz, which aims to challenge prevailing stereotypes about masculinity. “There’s this pressure to just ‘man up’ and deal with it. We want to encourage men to reach out for help because we know what happens when they don’t.”

More on Broadview:

- COVID-19 brings new challenges for abuse survivors

- Raising any child is a challenge. Am I doing enough?

- After the Montreal Massacre

But rage is also tied to unfulfilled entitlement, says Rachel Giese, author of Boys: What It Means to Become a Man. “These notions of male supremacy are, for many, false promises,” she argues. “That’s not to say that we don’t live in a society where white people and men have privilege, but there is this message given to men implicitly and explicitly, from birth, that the world will bend to their will: the guy gets the girl, all of the money and all of the power. But not every guy gets to be the hero, and there’s a lot of resentment that this promise was made.”

An extreme example of rage induced by unfulfilled entitlement is the “incel” ideology, short for “involuntary celibate.” Its adherents hate women for their perceived sexual rejection. In May, Toronto police laid the country’s first terrorism charge for an alleged incel-inspired attack, after a woman was murdered at an erotic massage parlour.

Anti-violence programs for boys often aim to anticipate some of that frustration and channel it into healthier, more productive choices. One focus of Calgary’s WiseGuyz program, says Carter, is “how to react when things don’t go your way.” The program takes on clear trouble spots, including dealing with rejection. “We know that these issues are huge for youth.”

Joe Aung, now 17, participated in WiseGuyz two years ago, when he was in Grade 9. Every Thursday for about six months, he gathered with a group of boys to discuss things like homophobia and the gender pay gap — subjects that led him to “eye-opening” perspectives he hadn’t really considered. “We talked a lot about peer pressure and toxic masculinity, and about how…there are still ways that women are oppressed and [why] it’s important for us to be aware of that,” he says. “It really gave us, as a group of boys, the chance to talk about our experiences.”

WiseGuyz also addresses bystander behaviour — encouraging boys to become part of the solution even if they haven’t initiated a harmful act. “Someone might use a slang term for a woman’s body part, and someone else in the group will say, ‘Hey, we don’t use those words,’” says Carter. “Some of them have even called out their own moms for saying something crappy about their sister’s body.”

At Maine Boys to Men in the United States, “We help to build the skills that boys don’t often get the opportunity to build,” says executive director Matt Theodores. “It’s hard to imagine how boys and men can really be leaders around calling [out] their friends [for] pushing the limits of consent if they don’t understand how to listen to other people and understand the impact of their behaviour.”

Founded in 1998, Maine Boys to Men offers programs for middle school boys and for mixed-gender high school groups. Theodores says that the mixed-gender setting can be an asset at a time when social divisions are splitting along gendered lines.

In the program’s mask exercise, participants write on the interior of a mask, describing both how they need to act in order to be perceived a certain way and how that experience conflicts with what they’re actually feeling inside. The masks are then redistributed anonymously, and other participants read them aloud. “They develop a huge appreciation for the experiences of others in the room that they otherwise wouldn’t really notice,” Theodores says.

Lana Wells is an associate professor with the faculty of social work at the University of Calgary, where she is leading Shift: The Project to End Domestic Violence. She supports these intervention programs for boys because they have what she calls a “gender-transformative approach” — meaning that they address socialization, power and inequality from an intersectional perspective, including how capitalism and patriarchy benefit boys and men. “These programs help wake boys up and offer them critical-thinking skills when it comes to gender equality,” she says.

Educators and researchers have sought out a sweet spot in talking about these themes and challenging common assumptions. Deinera Exner-Cortens, who studies WiseGuyz and similar interventions as an assistant professor in psychology at the University of Calgary, says that grades 7 to 9 are considered ideal for this kind of outreach for several key reasons: early adolescence is a time when dating and romantic relationships start to become more salient; when kids like to question the narratives they’ve been told; and when they’re able to form abstract ideas and apply them to their own lives. It’s also a period of autonomy-seeking and intense identity exploration, including around gender.

Carter of WiseGuyz says that this is also a pivotal age to reinforce the importance of peer relationships among boys, who are less likely than girls to keep close friends and confidants. “Once they hit high school, they aren’t as willing to be vulnerable, so they really need tools to start building those strong, foundational relationships,” she says. “We want to make sure that once they need to start having those more intense conversations about their lives that they have the skills to do that.”

While evidence that these programs actually work is largely anecdotal, some research is starting to back it up. Exner-Cortens calls preliminary results from WiseGuyz “super promising….[They’re able to] target sexual health, violence prevention and mental health,” she says. She and other researchers at the University of Calgary have seen improvements in bystander behaviour and sexual health self-advocacy in boys who attend WiseGuyz sessions.

“It’s very hard to change a single boy; you have to change boy culture. That’s why these programs for young men are so important.…It’s not just about the bully; it’s about who’s cheering them on and who’s doing nothing at all.”

Rachel Giese

But Sara Crann, a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Windsor who is working on a sexual assault resistance program for high school girls, says that many of the programs for boys have not demonstrated long-term effectiveness. “They tend to show positive changes for men’s attitudes about sexual violence, but those attitudes drop off after three to six months, and there’s no change to perpetration rates,” she says. “It speaks to how ingrained in our culture and society those attitudes that support sexual violence really are.”

Green says that it’s asking too much of these programs to assume that they alone can bring about broader social change. The work he does in the classroom needs to be connected to a larger strategy to reduce gender-based violence.

“Behaviour change is really, really tough. We think we can translate some knowledge and nudge some attitudes, but you really have to moderate expectations,” he says. “I will have a class one day that just goes so amazing that you walk out and hover a foot above the ground. You think, ‘We just solved misogyny today.’ And then you see something online a little later and remind yourself that no, you didn’t.”

While working on her book, Orenstein found that even impressively insightful boys quickly reverted to traditional views when asked about male archetypes. “It was like they were channelling 1955,” she says. “The conventional values like dominance, aggression, wealth, athleticism, sexual conquest — and, particularly, emotional suppression — came roaring back to the fore.” Those views are bolstered by any number of influences, including parental role models and popular culture.

The mother of a teenage son, author Rachel Giese says her research has changed her parenting and taught her the value of addressing these issues head-on in the home. “As a feminist and queer woman, [I have had] lots of conversations around language in the music he likes,” she says. “I was never one to say, ‘You can’t listen to that song,’ but I would say, ‘Okay, keep listening to that song, but now we’re going to have many conversations around the dinner table about what that word means so you can listen knowledgeably.’”

This emphasis on open and ongoing family discussion is important. Rewriting the traditional scripts of masculinity to build healthier narratives is an exercise in imagining how a million exchanges could go differently, how violent encounters could be avoided and how years of simmering anger and self-loathing could be alleviated. “It’s very hard to change a single boy; you have to change boy culture,” says Giese. “That’s why these programs for young men are so important.…It’s not just about the bully; it’s about who’s cheering them on and who’s doing nothing at all.”

And yet the factors and patterns that contribute to gender-based violence are so interlaced that these programs can only do so much. “We have to look at the home, where people congregate, and the external media and socialization,” says Wells. “It’s super complex, and there’s no silver bullet.”

This story first appeared in Broadview‘s October 2020 issue with the title “Raising better boys.”

***

Sarah Treleaven is a writer and broadcaster in Nova Scotia.

I hope you found this article from Broadview engaging. The magazine and its forerunners have been publishing continuously since 1829. We face a crisis today like no other in our 191-year history and we need your help. Would you consider a one-time gift to see us through this emergency?

We’re working hard to keep producing the print and digital versions of Broadview. We’ve adjusted our editorial plans to focus on coverage of the social, ethical and spiritual elements of the pandemic. But we can only deliver Broadview’s award-winning journalism if we can pay our bills. A single tax-receiptable gift right now is literally a lifeline.

Things will get better — we’ve overcome adversity before. But until then, we really need your help. No matter how large or small, I’m extremely grateful for your support.

Jocelyn Bell

Editor/Publisher