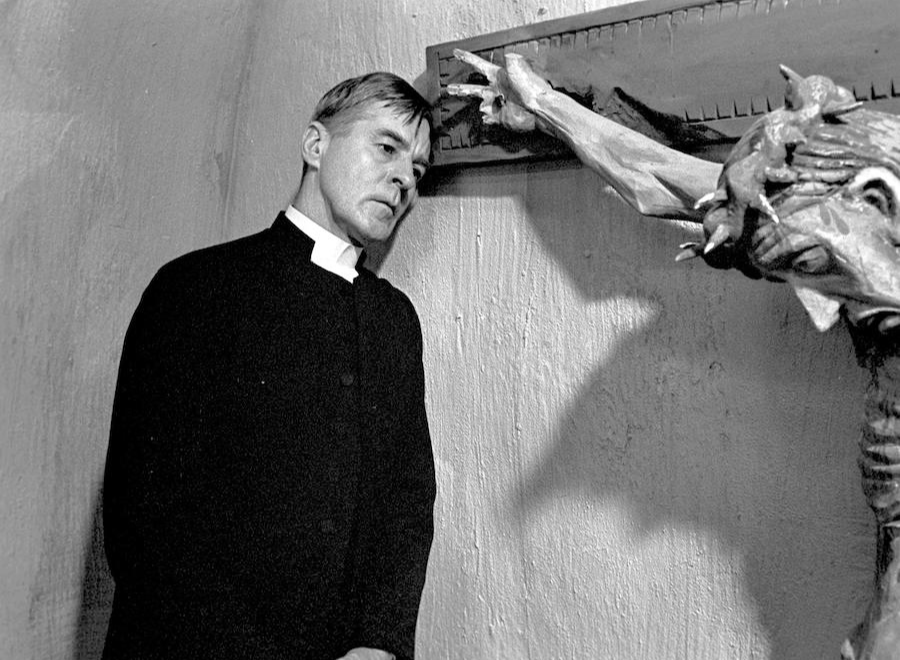

Exactly halfway through Ingmar Bergman’s 1963 film Winter Light, pastor Tomas Ericsson crumples under the weight of his anguish and admits, finally, that life would be simpler if there were no God. Up until this moment, religious doubt simmered quietly within the pastor, our main character — an internal struggle visualized by Bergman with long, brooding scenes inside a remote Swedish chapel. Now, a flu-ridden Tomas sits across from Jonas, a congregant in the throes of his own existential despair, and the priest cannot offer hope. Instead, he tells Jonas that if there were no God, we would no longer need to reconcile the existence of cruelty and suffering. “What a relief,” Tomas says.

Bergman made Winter Light at the height of his success — the iconic scene of a man playing chess with Death in 1957’s The Seventh Seal cemented his status as one of the best directors in cinema. At a time when he could have done something much larger and more broadly appealing, he opted instead to make what he described as a “brave” film: a gloomy, quiet meditation on faith and doubt that reflected his existentialist anxieties. The son of a stringent Lutheran pastor, Bergman placed a little bit of his father and himself into the character of Tomas, a bitter priest tormented by God’s silence after experiencing his wife’s death and the violence of war.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

In cinema, the internal turmoil of a doubting minister has been depicted in a number of films. Perhaps it’s a bit of a cliché by now, but there’s still something profound about the concept of a spiritual leader in the grips of a crisis of faith — something so earnestly existential. For these clergy characters, presumed by their followers to possess an unshakable faith, the uncertainty is inherently isolating. Admitting doubt would also mean failing those, like Jonas, who look to them for counsel. It could mean being expelled from their church or community.

Before Winter Light, Robert Bresson’s 1951 film, Diary of a Country Priest, also focused on a sickly pastor grappling with his faith. The film follows a naive young priest arriving in a remote French village to join his first parish. The locals receive him cruelly, mistaking his innocence for foolishness. Throughout, the unnamed priest suffers from debilitating stomach ailments. His faith falters alongside his health. When he discovers he has stomach cancer, he describes a “physical revulsion to prayer.”

Over half a century later, American screenwriter and director Paul Schrader paid homage to the two films with First Reformed (2017). This time our desolate clergyman, Ernst Toller, is played by Ethan Hawke, who serves as a mix of both prior priests. He suffers from grief and stomach pains, and amid his weakening faith is unable to comfort a depressed congregant.

More on Broadview:

All three films present their priest with the suicide of a congregant, catalyzing an even deeper plunge into their spiritual crisis. In 1942, French author Albert Camus famously claimed in The Myth of Sisyphus that suicide was the only serious philosophical problem. “Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy,” he wrote. The central question of suicide is if life has any meaning at all. While Camus asserted that life is meaningless and we should accept that, other philosophers like the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard said that life is meaningless and we should, instead, find our own meaning, be it in religion or not.

In Country Priest, we see this when, on his deathbed, the priest finally smiles despite his despair and says, “All is grace.” In First Reformed, Ernst ends up choosing the love of a woman instead of violence in the face of his existential angst. In Winter Light, the film ends with the poignant image of Tomas facing an empty church and deciding to deliver his sermon anyway, while Marta, an atheist in unrequited love with him, bends to pray on her knees. It’s not so simple that Tomas has overcome his crisis or that Marta is now a believer, but both have chosen to find meaning in these small acts.

A core theme in Winter Light, and much of Bergman’s work, is the idea of God’s silence: the lack of concrete reassurance of God’s existence. It’s also the central tenet in the aptly named Silence (2016), Martin Scorsese’s historical film based on the 1966 novel of the same name by Shūsaku Endō. Set in 17th-century Japan, where Christianity was persecuted, the story follows a young Jesuit missionary, played by Andrew Garfield, as he watches the immense suffering of Japanese Christians and grapples with God’s silence.

There are pinnacle moments in Winter Light and Silence when our suffering priests proclaim in despair, “God, why have you forsaken me?” Jesus spoke the same words on the cross. They feel symbolic of his doubts — his humanness.

One of Scorsese’s earlier religious films, The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), was controversial for what more conservative Christian groups deemed “blasphemous” depictions of Jesus. The film’s most thought-provoking scenes depict Christ’s temptation to live as a man, married to Mary Magdalene and raising children, free from the burden of being the Messiah. Ultimately, he overcomes this last temptation and fulfils the fate of his crucifixion. But the thought experiment of Jesus doubting himself rings with the same poignancy as a priest contending with faith.

Existentialism need not be the concern of only morose men. English actor and screenwriter Phoebe Waller-Bridge approached the same topic brilliantly and hilariously in the second season of her dramedy series Fleabag. The unnamed title character finds herself falling in love with a priest — nicknamed “Hot Priest” by fans of the show — who has vowed celibacy. After a season’s worth of push and pull, where Fleabag finds herself competing with God for the priest’s attention and he wrestles with the same choice, the priest chooses his faith. When Hot Priest says he can’t be with her, she asks, “It’s God, isn’t it?”

Despite their bleak premises, the films about doubting clergy end in surprisingly hopeful tones. Though Bergman was no man of God, he still decided to include Algot, a disabled sexton, in Winter Light — a character he described as an angel, who speaks to Tomas about how God’s silence on the cross must have hurt Jesus more than any physical suffering. After this conversation, Tomas chooses to go on with his scheduled sermon, despite the empty pews. This image, Bergman once said of the film, was enough to portray a stirring within Tomas — a new kind of faith rising from the embers of the old.

***

Ayesha Habib is Broadview’s associate editor.