It has taken more than a century – one that saw abuse of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children and a colonial mindset rooted in racial prejudice – but the vision of an Indigenous leader who believed in peace and harmony is becoming a reality. A concrete symbol of healing and reconciliation stands today in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. because of one chief’s convictions, and residential school survivors’ determination to create something good out of pain and suffering.

The same building that once housed a residential school now houses the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre (SRSC) at Algoma University. In classrooms, Indigenous students can explore their heritage and non-Indigenous students can discover this important and often-ignored part of North American history, and in the National Chiefs’ Library and Archive, part of the SRSC, a collection of Indigenous documents and data is growing.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The centre has also expanded into a research and education arm of Algoma called Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig, an Ontario-accredited Anishinaabe post-secondary institution that began offering programs geared specifically to Indigenous students in 2008.

More on Broadview:

- The heartbreaking and deeply Christian task of presiding over fentanyl funerals

- More older women are drinking too much. A new sobriety movement aims to help.

- What to give up for Lent when we’ve already given up so much

Colter Assiniwai, from Couchiching First Nation, Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation, is a history student at Algoma. He says that his exposure to Anishinaabe culture was cemented by his participation in events at Shingauk Kinoomaage Gamig.

“Being born and raised in [Sault Ste. Marie] meant that I did not experience my culture first-hand except for the local pow wows, and through my parents and grandparents,” he says. “It was really easy to sit in on an event, whether it be a speaker of a traditional ceremony, and begin that learning process.”

“For years, I was scared of doing this because I feared doing it wrong and ‘needing to know better,’” he says. “My peers who engage deeply with Shingwauk, often having a greater knowledge of the teachings or the language (and often both) would teach me things, even if they did not intend on it. Truthfully, Shingwauk has completely enhanced my experience as a student and as a student leader.”

Elizabeth Edgar-Webkamigad is the director of the Shingwauk Residential Schools Centre. We talked in her office, across the hall from the SRSC. Her shelves are stocked with books by Indigenous authors and symbols of her heritage, including beaded bookmarks bearing the “Seven Grandfather Teachings.” She is holding a small wampum belt – about 20 centimetres long.

This is the Two Row Wampum Belt – two parallel purple streams in a white background – representing the first agreement reached between European newcomers and First Nations people. Wampum are small, cylindrical beads used to make ceremonial belts. Hers was commissioned from a local Indigenous artist and is a smaller replica of that original treaty belt.

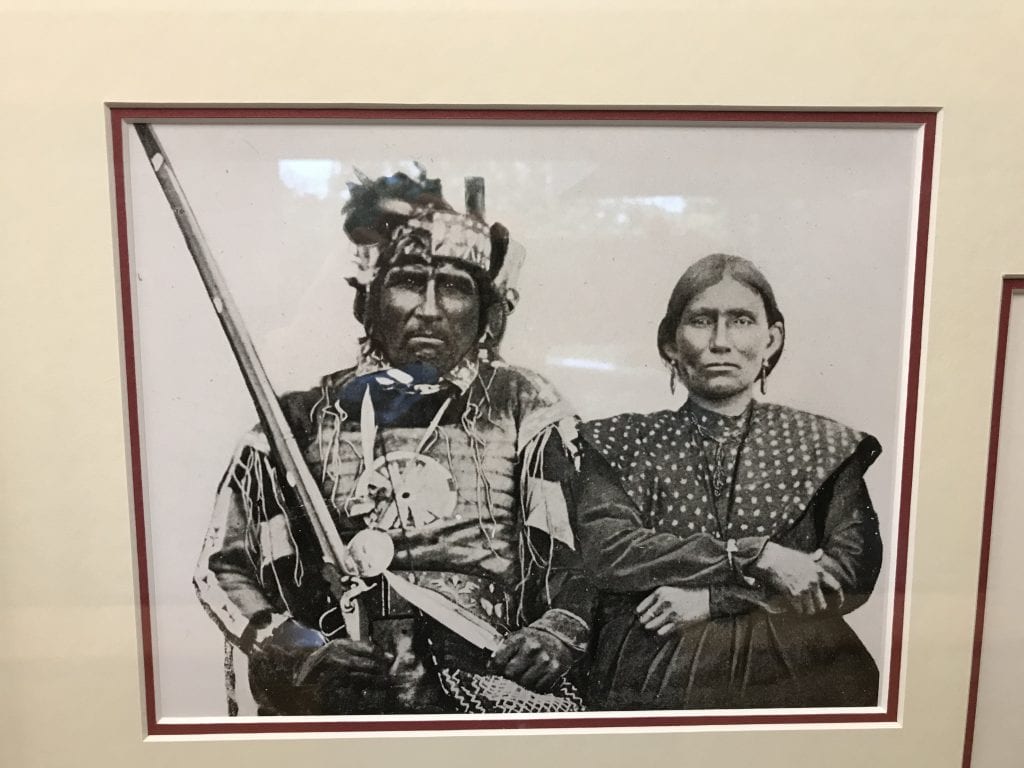

She also sees it as a powerful symbol of the remarkable vision of Chief Shingwaukonse (1773-1854), also known simply as Chief Shingwauk, the hereditary chief of Garden River First Nation until his death in 1854. His vision was carried on by his son, Chief Augustine Shingwauk, who served as chief from 1854-1890; their dream is continuing to take shape 130 years after his death.

“In this river of life, symbolized by these white beads, we have two boats,” she says. “This boat is the one that I am in – I am Anishinaabe, I am Ojibwe–Odawa–Potawatomi – and Creation has given to me all that I need to live the good life: songs, food, stories, culture, dance, my history,” Edgar-Webkamigad says. “Everything I need – my connection to the land, my connection to my family – is with me in my boat in this river of life.” The second boat, moving peacefully alongside the other, carries European newcomers to Turtle Island.

That, says Edgar-Webkamigad, was the vision that Shingwaukonse took to provincial government leaders in 1832, after travelling from Sault Ste. Marie to York (today, Toronto) by snowshoe, to advocate for a school. He believed that Indigenous people and European newcomers could not only co-exist, but learn from one another to their mutual benefit. He proposed a revolutionary idea – to found a school, a “teaching wigwam,” that would offer both Indigenous and European education.

He returned to Sault Ste. Marie believing that his proposal had been accepted. And for a brief time, it seemed to be unfolding as he had envisioned. But the school began to transition into a residential school, first as an “industrial school,” which taught vocational skills, and finally, in a new building that opened in 1935, as the Shingwauk Indian Residential School.

The residential school’s history is told through an extensive gallery exhibition on the second floor of the school. The information on the series of plaques and photos comes from personal accounts from the children who attended the Shingwauk Residential school, as well as the centre’s archival collection.

That school operated until 1970, although, as Edgar-Webkamigad points out, the last residential school in Canada remained in operation until 1996. Her parents attended residential schools elsewhere in the province, and she describes herself as a second-generation survivor. As was well documented across the residential school system, Indigenous children who came to live at Shingwauk Indian Residential School suffered physical and sexual abuse, and were deprived of their language, traditions and ceremonies.

When the school closed, the survivors, Edgar-Webkamigad says, confronted the reality of their horrendous experience and its implications. “Cultural genocide has happened, and there’s fallout, so, generations later, how do we fix that, how do we heal from that?”

In 1981, the survivors – officially, the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association – began to meet and to plan, committed to the 19th-century chief’s original vision. They worked with Algoma University to open the SRSC, located on the residential school building site, in 2005.

Today, the SRSC and Shingwauk Kinoomage Gamig (SKG), which has established its reputation as a significant Indigenous educational entity in the last decade, function in full partnership, says Edgar-Webkamigad.

SKG is one of nine Indigenous Institutes, or “teaching lodges” in Ontario. It will soon move into a new facility near Algoma. In 2017, the province of Ontario recognized Indigenous institutes alongside universities and colleges as a “third pillar” of post-secondary education in the province.

SKG programs are specifically designed for Indigenous students, while the Algoma classes and programs are open to all students, Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Both institutions include classroom work, but student experiences extend well beyond conventional academic settings. Edgar-Webkamigad describes the approach as “land-based and culture-based.”

Every student at Algoma – Indigenous, non-Indigenous, Canadian or from other countries – has the opportunity to include Indigenous courses in their more conventional study program, and also to participate in on-campus activities and ceremonies ranging from smudging ceremonies to full moon ceremonies.

She adds, “In the fall time, [if] any of our community members have a successful hunt and want to donate a deer or a moose, we will literally have a deer or a moose hanging on the property.” All students are invited to participate in harvesting the meat and the hides.

The impact of these experiences and studies goes well beyond the intellectual.

Mitch Case, former director of student services, outreach and resources at SKG and a “citizen of the Métis Nation,” says that when he worked in a classroom at SKG, he would teach at least five students each year who were intergenerational residential school survivors and knew nothing or very little about residential schools.

“And they had a grandparent or sometimes a parent who had attended,” he says. “So there is a lot of work that happens in Anishinaabe studies, especially, focusing on who are we as Anishinaabe,” he says. “We try to steer away from the Indian Act and these external definitions, and ask, instead, ‘Who are we as we define ourselves?’ and, ‘How do we express to the world our identity and our history and our stories?’”

He says that in the second year of the course he taught, he focused on social issues. “In order to heal, we must know the wounds,” he says. “So we have to explore — where did this trauma come from, where did this history come from? Incredible healing happens in that classroom for those students.”

He adds that while it was very encouraging to watch students find healing and closure, his heart breaks for the many survivors and their children who have not had that opportunity. “There is a lot of work to be done.”

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of the closing of the residential school. Plans to celebrate the event with large physical gatherings were put on hold for obvious reasons, but there were likely still heartfelt personal celebrations held throughout the Shingwauk-Algoma community. “When you look at what Chief Shingwauk wanted, back in the 1800s, what a wise man!” says Edgar-Webkamigad. “And now, finally, we are all working toward bringing the effort of bringing that dream to life.”

***

Would love to visit, wish it were not so far away from Hamilton, planning to visit Woodland in Brantford though.