For Native writer Thomas King, stories are the essence of our humanity. Stories tell us who we are, where we are from and where we are going. “The truth about stories,” he boldly proclaimed in his 2003 CBC Massey Lectures, “is that’s all we are.”

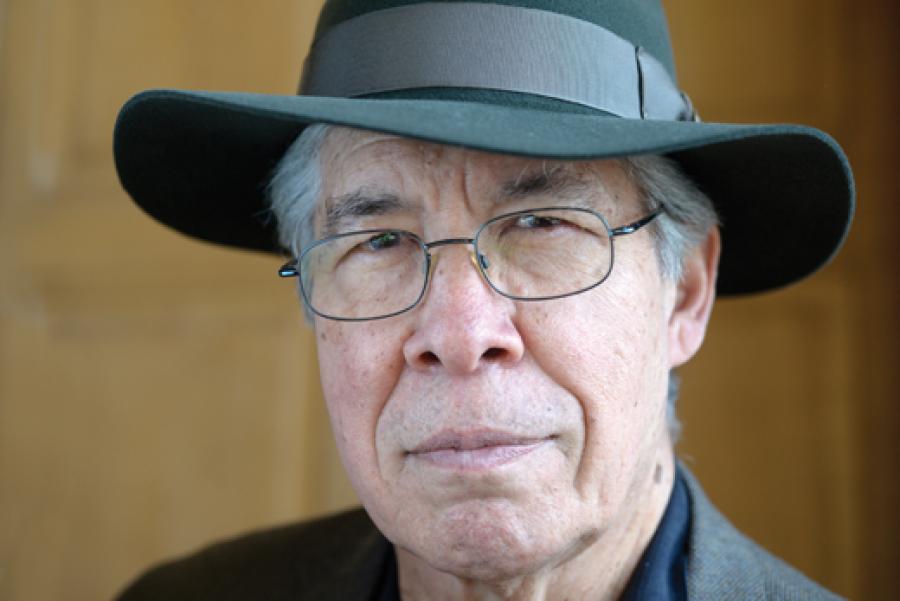

If stories are the bedrock of human identity, then certainly King himself has played a powerful role in shaping Canadians’ ideas of themselves and their country. With fierce intelligence and potent wit, his writing tackles the subject of cross-cultural interaction between Natives and non-Natives. Anyone who has read King’s fiction — his works include a children’s book series, several short story collections and three novels — will know that he is among this country’s most gifted storytellers. Fiction is his forte, stories his second skin. Yet his newest book, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America, is an uncharacteristic foray into non-fiction, in the genre of historical journalism.

Truth be told, King doesn’t seem all that comfortable with the transition. He knows that he is a storyteller, not a historian, at heart. “I dislike the way facts try to thrust themselves upon me,” he acknowledges at the outset. “I’d rather make up my own world.” King tries to resolve this dilemma by concocting an eclectic mix of storytelling and reportage. His fascinating fusion underscores his point that history is less a series of dates or hard facts than a narrative built on our collective desires and ambitions.

King says it better: “Most of us think that history is the past. It’s not. History is the stories we tell about the past. That’s all it is. Stories.” He backs up this claim with some pretty convincing examples, from a massacre that didn’t happen despite what the history books say, to a reputed love affair between Pocahontas and John Smith that is based entirely on the word of a power-hungry adventurer.

Why are we so invested in a history made up largely of myths? Because, King says, we like our myths too much to give them up. Even if we knew the truth of the past, we would still hold on to its mythic versions. Our collective desire to believe, say, that Pocahontas and John Smith were lovers — that the Native princess surrendered to the European — is too overwhelmingly strong. Through a vast survey of the stories that circulate about Native people in North America, King shows that our popular culture is besieged with savage, stupid and dying Indians. It’s not that North Americans haven’t associated with real, living Native people, but that the latter have become largely invisible. Rather than “see” the humanity of the Natives in their midst, most non-Natives have reduced entire cultures and peoples to stereotypes and clichés that say more about the dominant culture than anything else.

Given King’s scathing political critique, it’s impossible for any non-Native person to read The Inconvenient Indian without occasionally squirming with self-conscious discomfort. It’s also impossible for any non-Native Christian to read this book without experiencing moments of profound shame. King is justifiably angry about the treatment of Native peoples in this country, and much of his rage is squarely aimed at Christian institutions and practices.

Christianity, colonialism and capitalism make up what he sees as the triumvirate of cultural assimilation. Never, he claims, has Christianity been interested in cross-cultural collaboration. Its only aim has been the total capitulation of Native peoples to a supposedly superior culture. Residential schools, he notes, are a glaring case in point. King’s damning indictment of Christian arrogance is a harsh but necessary reminder of the dangers of unwavering religious certitude.

One wonders if King oversimplifies the deeply complex relationship between First Nations people and Christianity. After all, while some Native people have thrown out the Christian baby with the colonial bathwater, many others have critically embraced the faith or integrated it into Native world views. That said, King’s bitterly cynical approach offers an important alternative to the more hopeful narratives that have become so popular in public discourse.

Many onlookers herald Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as a new chapter in the relationship between Natives and settlers, but King contends that reconciliation is more empty rhetoric than emerging reality. Dismissing Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s five-year-old apology to residential school survivors as “disingenuous,” he insists that apologies — authentic ones, anyway — must be followed by action. The book’s final chapter, ironically called “Happy Ever After,” is a mocking refusal of romantic endings and the naive Hollywood-style optimism favoured by North American audiences.

In an interview with the Globe and Mail, King describes The Inconvenient Indian as more “strident” and “unforgiving” than his previous work. He is right: this book is devastatingly forthright, and as such, a distinct departure from the exuberant and celebratory qualities one finds in his fiction. King the historical journalist is a different kind of writer than King the storyteller. The latter is funnier, gentler, more entertaining and certainly more magnanimous than the cutting and caustic voice of this polemic.

If you are new to King, begin with his fiction first — his brilliant novel Green Grass, Running Water,any of the sidesplitting tales collected in One Good Story, That One or an audio recording of the scandalously funny Dead Dog Café Comedy Hour that he created and wrote for CBC Radio. All of these works are astonishingly politically incorrect, exaggerating our expectations or inverting stereotypes at every turn.

Once non-Native readers realize that they are the butt of the jokes — the position that Native readers have historically found themselves in — the real education begins. As Margaret Atwood said of his stories, “They ambush the reader. They get the knife in, not by whacking you over the head with their own moral righteousness, but by being funny.”

If his fiction delights and instructs non-Native readers with its irreverent comedy, The Inconvenient Indian delivers a massive blow to the head. Then again, perhaps the time for joking is over, and such force is precisely what is needed at this critical time in Canadian history.