Set in a rural Mennonite community in southern Manitoba, Shelterbelts is the debut graphic novel by illustrator and designer Jonathan Dyck. Now based in Winnipeg, Dyck grew up as a pastor’s kid in the largely Mennonite city of Winkler, Man., and his fiction draws on this background with empathy and insight.

The book jacket describes shelterbelts as “lines of trees that act as windbreaks for farmers’ fields in southern Manitoba.” But these green sentries are not entirely benign: “their grid-like presence on the land is a direct result of settler-colonial interests.”

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Dyck says that he has written each of the 10 linked stories in the book as a shelterbelt. And so as the characters in this small, historically traditional community wrestle with change, both in their own lives and in the outside world, we see how, like a shelterbelt, some decisions and beliefs can both offer protection and cause harm.

In one of the stories, “As the Deer,” the adult granddaughter of a conscientious objector tells an older Mennonite couple about how her grandfather refused to fight overseas in the Second World War yet became a teacher at an Indian residential school. “Well, that’s better than going to war,” says the husband. “Is it?” the granddaughter questions. “We sure can’t call it peace. Not when we know what happened at those schools, why they existed in the first place.” After she apologizes to the couple for burdening them with her story, the wife says, “No, you’re right to mention it. We’re so accustomed to seeing ourselves as exceptions.”

More on Broadview:

- ‘The Porter’ showcases Black Canadian train workers’ historic fight for equality

- ‘Night Raiders’ shows the power of sci-fi and horror to illustrate Indigenous experiences

- Ivan Coyote’s new book is a study in the healing power of letters

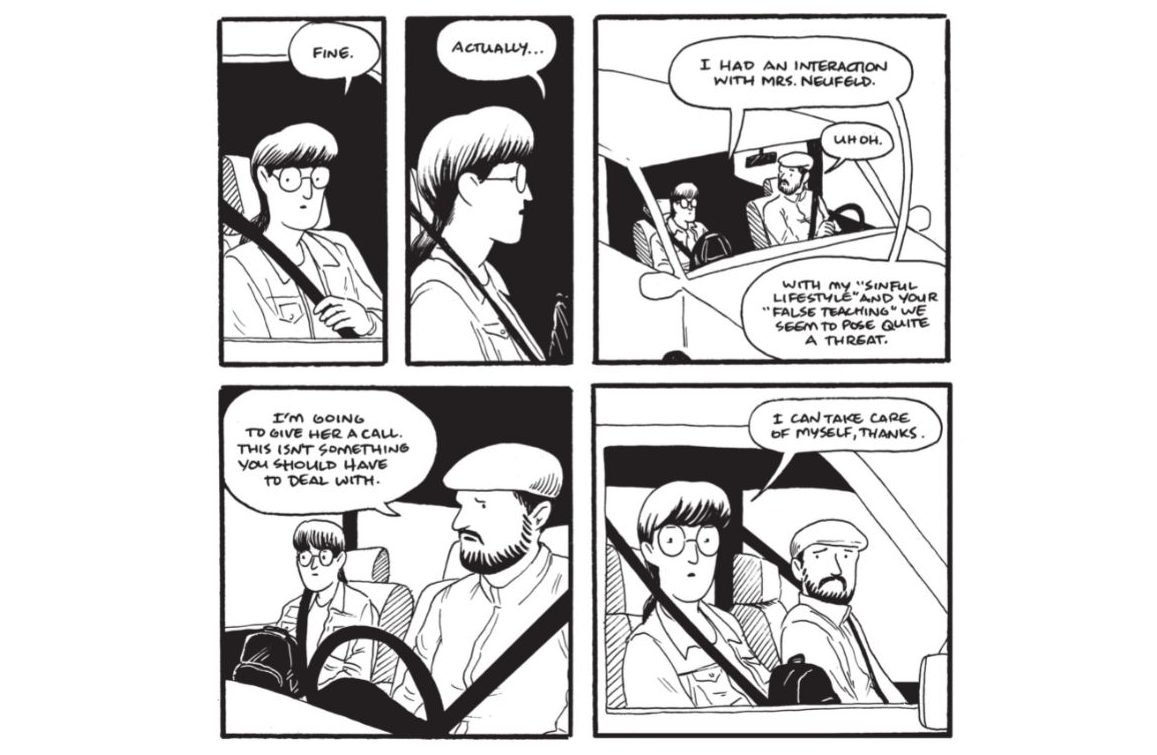

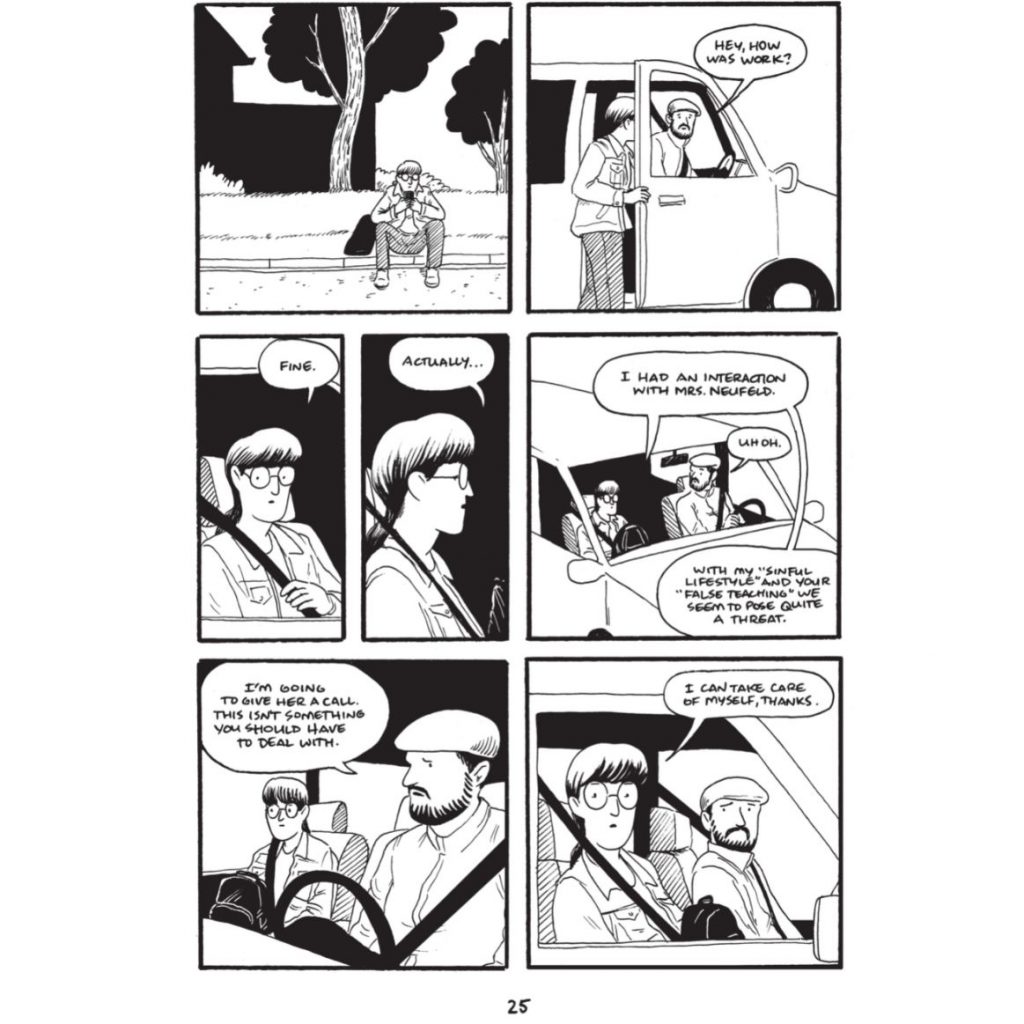

Shelterbelts explores the many layers of these characters. For instance, we’d learned in an earlier story that this same couple had just left one of the local Mennonite churches because it became “far too worldly” — code for too inclusive of LGBTQ+ people. The stories of the pastor of that church and his daughter, who is gay, are also shared in the book. And not all of the characters are Mennonite. Jason, who is Métis, reflects on the role Mennonite settlers played in pushing his ancestors off this territory, telling his partner, Rebecca, that he and his family used to take day trips there when he was little to visit a site sacred to his relatives. Driving back through the area, he stops at a trail. “This place. I feel like I know it. Like it knows me.”

Dyck’s storytelling is superb, and through his sensitivity and eye for detail, often conveyed wordlessly through his thoughtful drawings, he fills in a picture of life in this community. While the stories are often particular to the Mennonite world he knows so well, they speak to a wider audience in their humanity and emotional depth. Because we are all capable of building shelterbelts.

Alex Mlynek is a writer in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s June 2022 issue with the title “Prairie fault lines.”