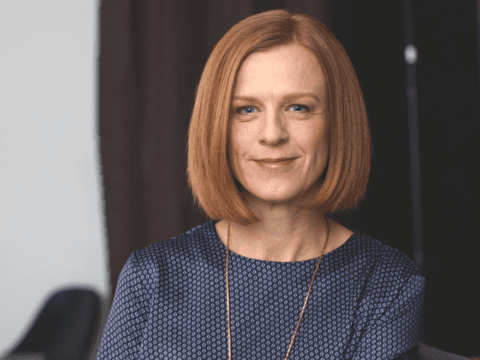

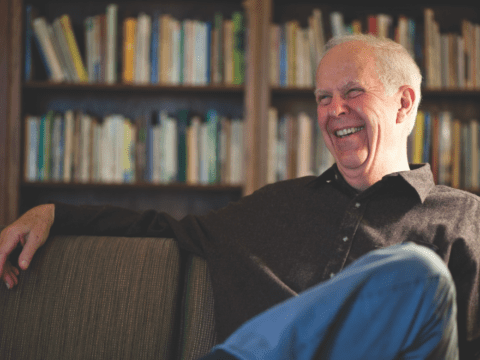

Theology-school dropout Shane Claiborne, 36, is drawing thousands of evangelical and mainline youth into Jesus-centred communities of environmentalism, anti-militarism and service to the poor. He spoke to Pieta Woolley in Vancouver.

PIETA WOOLLEY: Your book The Irresistible Revolution invites readers into a life of “ordinary” Christian radicalism. Why is the revolution “irresistible”? Giving up materialism seems very demanding.

SHANE CLAIBORNE: I think there’s a deep longing among all of us to live for something bigger than ourselves. As much as we try to hide that with the illusion of independence and materialism, that nagging desire for love and community keeps resurfacing. [Catholic activist] Dorothy Day said the Spirit is like the hound of heaven. It chases us down. It catches us. Everywhere we go, people are packing rooms to dream about what it means to love God and love their neighbours.

PW: You’re one of the founding members of an intentional Christian community in Philadelphia, the Simple Way. How is what you’re doing different from the Jesus freaks of the 1960s and ’70s?

SC: The Jesus freaks wanted Jesus without the church. They were leaving the church and starting their own communities. What we are doing, as St. Francis said, is trying to repair the ruins of the church. So we’re trying to work for renewal within the traditions: to help Methodists read John Wesley again; to help Salvationists read William and Catherine Booth again; and to co-opt the best of our traditions. We’re a part of local congregations. How conventional is that? We’re not church planters. We’re at Catholic mass on Sunday mornings; we’re worshipping with the Mennonites. That is one thing that’s pretty unique. We’re not trying to be the church without the church. We’re trying to create vibrant, healthy communities that form disciples who fit into God’s holy counterculture.

PW: What would you say to parents who balk when their own kids say, “We want to have simple lives and live in community,” instead of pursuing a career?

SC: Trust Jesus. There’s a reason that when all the angels come, they say, “Fear not!” When we started our community, my mom was pretty unsettled about a lot of the things we were doing. But the more she saw our neighbours’ kids sleeping on the floor of abandoned houses, she started to understand: “I know why you gave your couch away that I bought you. I know why you gave the winter boots that I got you away.” I think parents need to be grateful that their kids are taking Jesus and his teaching seriously.

When I went to Iraq [as part of the Iraq Peace Team], my mom was devastated. And yet, there was a moment in her tears when she said, “Those children in Iraq are as precious as you are. Moms and dads are weeping over them too.” In the end, she was really supportive of my going. That’s the release we’ve got to have: the sense that children are precious — but so are other people’s children. And some people’s children are starving to death and suffering from bombs and poverty. If my kid lives with a little discomfort in order to comfort someone else, then thanks be to God for that.

PW: The churches I know of want what you’ve got. They want engaged youth and young adults, and often they’re failing miserably. What do you tell them?

SC: To pray for imagination. The church must rethink what it means to be Christian in the world we live in. The questions that young people are asking are really great questions — about the patterns of Wall Street, the super-rich, the super-poor, imperialism. Those are the exact same things Jesus was talking about. So I think that we need to be asking those questions.

PW: What turns youth off?

SC: This generation of youth give more generously than any other in history, yet they give less money to the church. Why? About 95 percent of church budgets go to staff and buildings. “Missions” shouldn’t be a line item — it should be our budget. So maybe that means reconsidering how we do paid staff. Alcoholics Anonymous is one of the most redemptive, pervasive communities out there, and its core foundation says, we don’t pay staff and we don’t own buildings.

PW: What would you say to introverts who shudder at the idea of living in community?

SC: We’re all called to some form of community. I’m not attached to one form or community; I don’t think everyone needs to move into a row house and share one bathroom. There are communities of introverts, and they have tons of alone space, but they’re still trying to live together and share money and live missionally.

Also, our cultural muscles for community have atrophied, so we don’t even know community. We’re taught independence. We even have Independence Day as the national holiday. Yet it’s the antithesis of the good news. The Bible says we’re not alone. You actually do need people; you do need God. That’s a good thing.

PW: I’m intrigued that you express yourself to youth through traditional media, especially when so many churches are trying to Tweet themselves into relevance. You write books and magazine articles, you appear in films and you speak in person. What are you thinking?

SC: I see the Internet as a power drill — it’s a tool, and we should be careful that we don’t use it everywhere. I’m a storyteller at the end of the day. I think stories are transformative. I know very few people who have been argued into a new reality. But I think we can story people in, and I think we can build relationships that bring people in and communicate politics and theology and ultimately bring us closer to where we’re meant to be. Jesus was a storyteller. At best, I’m a pop theologian — but I’m a decent storyteller. That’s what I do. [Claiborne claims he doesn’t know how to log in to Facebook.]

PW: Do you get blowback for your stand against militarism?

SC: Not in Canada! [Laughs.] Yeah, surely. There’s a cost to speaking truth and love, and there’s a cost to not speaking truth and love. And I’m certainly more interested in saying what I believe is true to Jesus, whether it wins you an award or gets you a nasty letter. I do try to take critique very seriously. On the other hand, just as there’s criticism, there’s an overwhelming tide of folks who are tired of militarism; they’re tired of seeing “Live by the sword, die by the sword” played out. And they’re suspicious of the myth that violence can bring peace. I’m really thankful for that.

PW: How do you feel about being a celebrity?

SC: Is that what I am?

PW: Yup.

SC: There are two responses folks have to being influential. One is to romanticize it and get caught up in the hooray and the hype and the power. The other is to sabotage it, saying we shouldn’t be talking to tons of people or writing books, we should just be living small in our neighbourhood. A buddy of mine — he’s a rock star, so he knows what it means to be a celebrity — taught me a prayer: “God forgive me for thinking too highly of myself; God forgive me for thinking too lowly of myself; God forgive me for thinking of myself so stinkin’ much.” I think that’s a beautiful prayer. Mother Teresa said our goal is not to be successful but to be faithful. To me, when we’re faithful, you never know whether that’s going to win you an award or get you on the cover of a magazine, or whether that’s going to get you put in jail and killed. Both have happened. So I think I tend to focus not on the effects but on the faithfulness, and not allow that stuff to distract from what we’re called to do.

PW: When I think about young people who have a vision and speak out, and people pay attention, you’re right, they’re often killed. Does that keep you up at night?

SC: No, not really. I’m not that scared of dying. I’m scared of not living. . . .Martin Luther King went to talk to a bunch of sanitation workers in Memphis, and people told him not to. And he said, “I can’t not do this.” We must allow that kind of compelling conviction to move us.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2012 issue with the title “Parents need to be grateful that their kids are taking Jesus and his teaching seriously.”