My mother was a member of the Beaver Lake Indian reserve and my father a member of Saddle Lake, two different reserves but both signatories to Treaty 6, located in what is now called northeastern Alberta. As a nehiyô (First Nations Cree person),* I am honoured to share how I have come to miyo pimatisiwin (living the good life).

I begin with some teachings from Vine Deloria Jr. (Sioux) and his book God Is Red: A Native View of Religion in which Deloria elevates Native American spirituality and practices to be equal to those of the foreign Christian religion. Deloria’s analysis called to attention my misguided actions and ways. Up until that point in my life, I had been looking outwardly at the colonial system and holding it above my nehiyô (Cree people) and nehiyaw pimatisiwin (Cree world view and/or way of life). But now I profoundly understood that Indigenous ways of knowing and being are equal to that of foreign ways of being.

After reading God Is Red, I then picked up a copy of Deloria’s For This Land: Writings on Religion in America. In the essay “It Is a Good Day to Die,” the following quote shook me to the core:

In the Indian community there has always been the acknowledgement that living cannot be postponed.…“It is a good day to die,” Crazy Horse used to call as he rode out into battle. People accepted his challenge and followed him because he called into question their highest memories of themselves. If there is a sense, then, in which a person can have a vocation, it is to ride into one’s community with a challenge to its presuppositions, presuppositions which one cherishes and from which one’s identity is received.

As a Two-Spirit community organizer, I answered this metaphorical question or call with a resounding desire to work for better tomorrows for my Two-Spirit and Indigenous relatives — free of systemic and internalized oppression such as racism, homophobia and transphobia, so others may not experience what I endured.

Next, I share with you a story I heard a few years ago and that has stayed with me. In October 1492, Christopher Columbus made landfall in what is now the Bahamas. Columbus and his ships landed on an island that the Lucayan referred to as Guanahani. With hands outreached, these Indigenous people welcomed and sang Columbus to shore.

Fast forward to 2017, when Syrians were fleeing a global humanitarian crisis. This country, this land that settlers named Canada, had offered refuge to around 40,000 Syrians. Some Indigenous people went to airports and with hands outstretched, they welcomed the newcomers to this land and sang them to “shore.”

These stories are whispers from our ancestors reminding me of who I am, where I come from and what my sacred teachings are as I work in service to my vocation and purpose.

More on Broadview:

- In her new book, Anishinaabe author Patty Krawec explores how creation stories shape us

- My faith has led me back home to myself as Cree

- An Indigenous minister answers the question: Why are you a Christian?

I endeavour to embody, to know and to sing my sacred teachings: WISDOM, to cherish all knowledge; LOVE, to know peace; RESPECT, to honour all of the Creation; COURAGE, to face the foe with integrity; HONESTY, with myself and the world; HUMILITY, to know myself as a sacred part of the Creation; and finally, TRUTH, to know all of these things and teachings.

I come from a long line of people who have survived collectively over 530 years of colonization. Every breath I take is an act of survival and every exhale is an act of resistance — or survivance. What matters more than ever is how I choose to respond or react to this simple truth and history.

We must remember our sacred teachings and who we are. There is such great medicine in that simple, powerful and healing act. Our collective and individual healing journey is remembering, knowing and being who we are as Indigenous Peoples, then breathing life into and walking our sacred teachings.

For this we live another day.

***

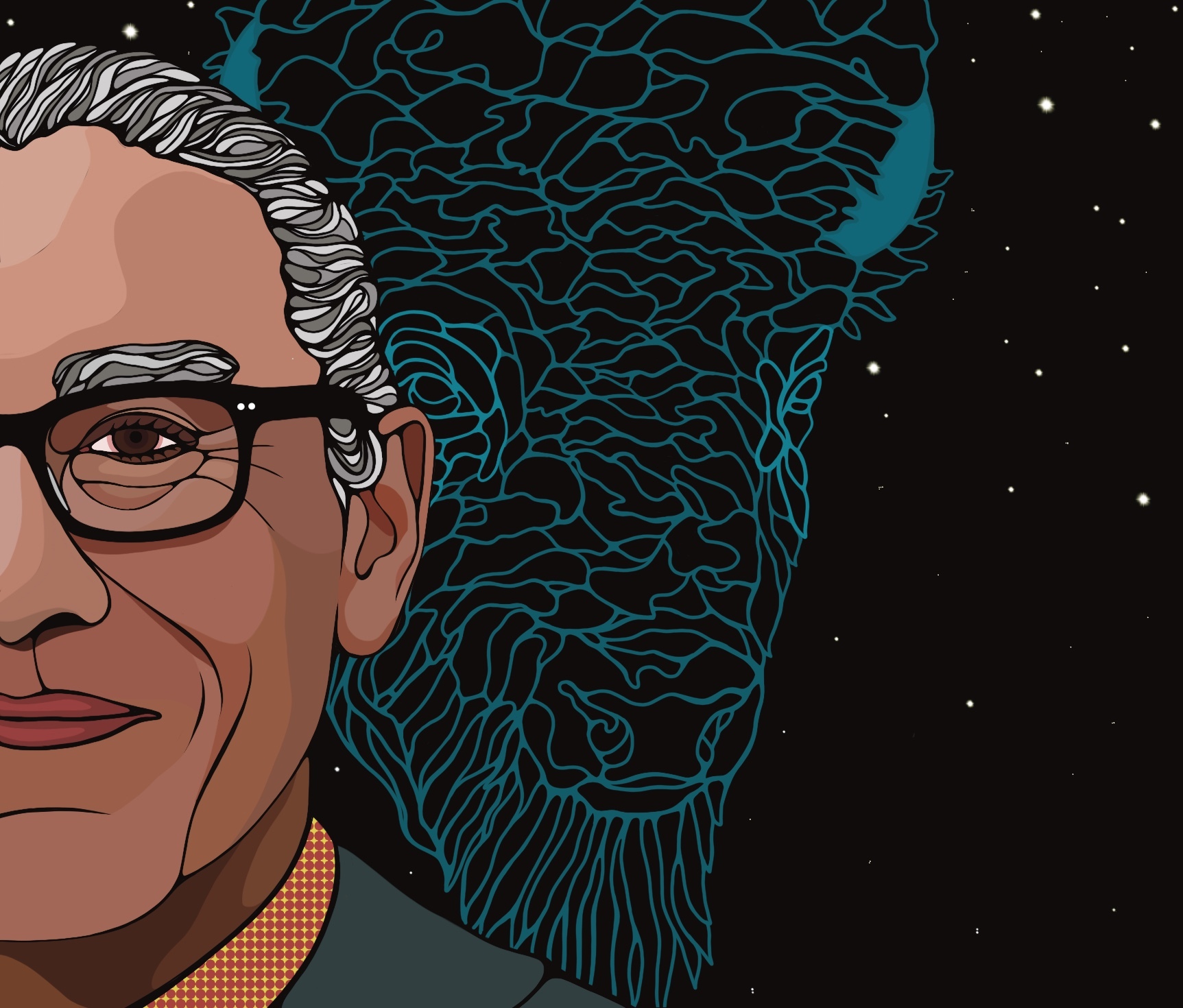

Harlan Pruden (nehiyô/First Nations Cree) works with and for the Two-Spirit community locally, nationally and around the world and is also a PhD student in the faculty of health sciences at Simon Fraser University in B.C.

*Italicizing foreign words is a western colonial convention. The practice of not italicizing Indigenous words but italicizing the translations is borrowed from scholars such as Alice Te Punga Somerville (Māori) and Tracy Lee Bear (nehiyô), and grounded in Indigenous ways of knowing.

This article first appeared in Broadview’s September 2022 issue with the title “Sacred teachings.”