Incense wafts out of the prison chapel, along with voices chanting, “Hail, Mother God. Hail, Mother God.” Inside, five pagans are gathered in a circle around a table topped with an improvised altar of candles, animal horns, feathers and rune stones.

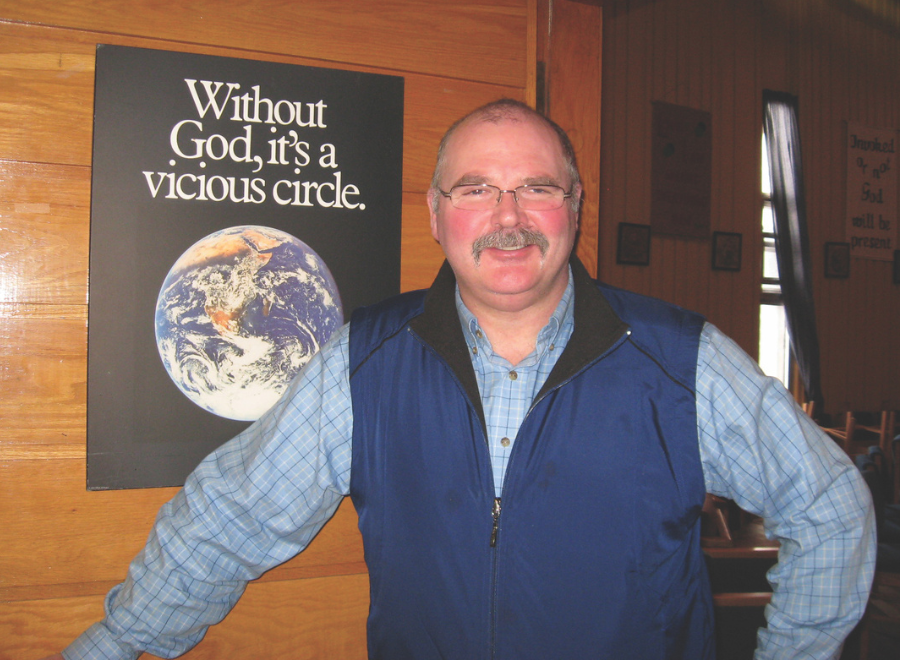

In his hallway office, closer to the entrance of the squat grey stone building, Rev. Lloyd Bruce is catching up on e-mails and paperwork — checking the daily pass list that tracks the movements of inmates in and out of his corner of Springhill Institution, a medium-security men’s federal penitentiary in the former coal-mining town of Springhill, N.S.

Welcome to prison ministry. It’s a part of Christian outreach as old as the faith, but usually out of sight.

Prison ministry surfaced as a public policy issue last year when federal Public Safety Minister Vic Toews cancelled Correctional Service Canada (CSC) contracts to part-time paid chaplains serving non-Christian inmates. This left federal Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh and pagan prisoners without qualified spiritual leadership. The United Church moderator wrote a letter to Toews urging him to rescind the decision.

Pagan and Muslim groups continue to meet at the chapel in Springhill, and Bruce tries to arrange visits from volunteer leaders. In small-town Nova Scotia, a two-hour drive from Halifax, it’s not easy.

As Springhill’s ecumenical Protestant chaplain, one of four United Church ministers among 73 full-time federal prison chaplains across Canada, Bruce works closely with a full-time Roman Catholic lay colleague on Christian worship, study and fellowship, as well as restorative justice and Christian-based self-help groups. Two First Nations elders, both under contract to CSC, lead Aboriginal prisoners in traditional spiritual practices.

Springhill is also home to the St. Luke’s Renewal Centre, the only retreat centre inside a Canadian prison. Both St. Luke’s and Spring House, a hospitality home in town for prisoners’ visiting family members, receive financial support from the United Church’s Mission and Service Fund.

Like Springhill’s almost 400 other prison staff, Bruce begins his working day in a lineup at the institution’s small entry building, waiting to pass through a metal detector. Bags and coats also get airport-style screening.

I’ve been pre-screened for security but have to show ID and pick up a visitor’s badge. A guard then buzzes us through a heavy metal door leading back outside, into a -18 C winter cold snap.

Next stop is the gym, where an administrator briefs staff on overnight incidents and any changes to routine: an offender threatening to harm himself was talked into giving up a sharp blade; contraband tobacco smoke was detected in a cell unit. Bruce has ready access to warden Jeff Earle and is welcome at management meetings. He skips it today.

The largest penitentiary in acreage in Canada, Springhill Institution was built in 1967 on a low plateau overlooking scrubby woodlands and the former coal-mining town. About two-dozen buildings, a few ball diamonds and a playing field sprawl across the property, which is surrounded by high double fences topped with razor wire and overseen by guards in watchtowers. Four two-storey brick buildings house cellblock units and parole offices. Two more housing units, with 182 cells, are under construction, part of a $40-million expansion plan.

The prison was built to house 448 inmates, but with some double-bunking it currently holds 475. Many are from the Maritimes, but others come from across Canada. Most of the population here is serving less than four years, but at least 10 percent are “lifers,” serving up to 25 years.

In official correctional parlance these days, inmates are called “offenders.” They more readily refer to themselves as “prisoners” or “convicts.” Bruce usually just calls them “the guys.”

Inmates’ time and movements are carefully controlled, with head counts several times a day. Unless they are in segregation or reception, prisoners eat in the dining hall, in shifts. They have keys to their cells and leave them locked while away at work, activities or programs. Cells are small and spartan, with a bunk, desk, toilet, sink and security-screened windows.

For Bruce, reaching the chapel means another chilly walk along an open-air concrete corridor, lined with pillars that seem to capture and hold the cold. At the central guard post, he picks up a brass chapel key and personal security alarm.

Bruce kibitzes with guards and introduces me to parole officers, who help prisoners plan their time inside. Options include joining life-skills, anti-addiction or anger-management programs; working; or studying as far as a high school equivalence diploma. College and university courses are no longer available. Jobs pay up to $6.90 a day and include cleaning, cooking, clerical duties, furniture-making or mechanical work.

Bruce also chats informally with many prisoners. One-on-one counselling takes place in the chapel office and consumes about half of his usual Sunday-to-Thursday workweek.

Because I’m with him, prisoners visiting the chapel are happy to talk to me and let me join their gatherings. But signing required release forms to let their names appear in print is another matter. Family members have already been hurt, and inmates fear speaking out could harm chances of parole or attract negative attention from prison staff.

A man who describes himself as “an old con” says, “The chaplain is the one we come to when things are not going well — when there’s heartache, there’s trouble.” And when things get dicey and the atmosphere in an institution grows dangerous, administrators also turn to the chaplains, he says. “The chaplains are the ones that have to sit in the middle.”

Bruce has been at Springhill for seven years, after serving congregations in Alberta, Ontario and New Brunswick. He is set apart from prison staff by more than job description. Like all chaplains and Aboriginal elders, he is not employed directly by CSC but works under contract. The federal agency pays the United Church’s General Council for his services. The church then pays Bruce.

“We walk that fine line between staff and inmates,” Bruce says. “I have to work in such a way that I’m accessible to everyone. If I err, I always try to err on the side of standing with the inmates. Because they are the ones with the fewest resources, the fewest allies in any situation.”

Recent budget cutbacks have reduced the quantity and quality of convicts’ food and have slowed processes — such as phone-list approvals — that help prisoners stay in touch with the outside world. But front-line prison officers, already working long hours, have also felt the pinch of shrinking budgets.

In addition to the pagans (Wiccan, Druidic and Asatru), Bruce’s ecumenical responsibilities include about a dozen Muslims who hold a weekly fellowship meeting at the chapel. Like the pagans, they’re unhappy about the lack of qualified spiritual leadership. They get special diets but grumble about the prison’s approach to daytime fasting during the month of Ramadan. Instead of calling Muslims individually for an early breakfast, guards woke everyone in their cellblock at 5 a.m.

During my visit, Bruce is called upon to determine whether an inmate requesting kosher meals is Jewish. He visits the man on a segregation unit, then contacts a rabbi in Halifax to determine what questions to ask. If the prisoner has the right answers, there’s the problem of finding a kosher meal supplier.

The Tuesday evening fellowship time is more like what most churchgoers would expect of prison ministry. This week, longtime volunteers Ron and Shirley MacDonald, part of a Pentecostal congregation in nearby Amherst, N.S., are here, along with United Church member Al Wallace from Enfield, N.S. “It’s just like coming to church with your friends,” says Shirley. “We love them, and they love us.”

The circle of chairs grows until it includes Bruce and 27 prisoners and visitors. After a quick prayer, Bruce opens by asking participants what they like to do to warm up on a cold winter evening. There’s singing and guitar playing. Bruce reads scripture and asks everyone in the circle to share some wisdom. The responses range from fervent Christian witnessing to hard-won life lessons and snippets of common sense. Wallace and the MacDonalds know many of the men well; they talk openly and laugh easily with them.

“The thing I’m most trying to do is to create a safe community where people can feel open enough to talk freely,” Bruce tells me later.

The worship wraps up with a spirited rendition of I’ll Fly Away. Especially the second verse: “When the shadows of this life have gone, I’ll fly away. Like a bird from these prison walls, I’ll fly. I’ll fly away.”

The guitar player does a virtuoso solo break, then starts another chorus. The session ends with handshakes and hugs.

Some of the men have neither spoken nor sung the entire time, but they line up for hot chocolate and cookies all the same.

A few prisoners claim innocence and are locked in long-term legal battles to clear their names. But most here admit they have made bad choices and have to look inside themselves to figure out how to change. Spirituality can play a part in that, in the chapel and at St. Luke’s Renewal Centre.

The white clapboard bungalow sits incongruously among the prison’s steel, stone and brick structures. Funded by donations and opened in 2000, the centre offers volunteer-led programs for inmates ranging from creative writing to tactics for staying out of prison. It also welcomes prisoners, in groups of five, for daylong sessions of meditation, talk and family-style life.

Kairos Marathons are another unique chaplaincy program at Springhill, bringing together inmates, volunteers and chaplains several times a year for intensive two-day group therapy circles.

Restorative justice circles also meet in the prison chapel. They’re yet another way to help inmates look at their lives and crimes and find a different path after release.

At the end of the day, the metal security doors lock behind us, and security procedures run in reverse, bags and coats coming back through the scanner. The air outside is still cold, but there’s an open sky and no razor-wire fences blocking the way to the parking lot.

Prison is neither a nice place to live nor an easy place to visit. But the work happening there is important, says Bruce. “One of the Gospel principles for me to remember is that Jesus brought the good news that you’re loved to those on the periphery of society.”

He says he believes in the prisoners, “as ones who have the capacity to change and to do good in the world. I believe in them as I hope others believe in me — and I do what I can to hold hope for them, especially when they can’t hold it for themselves.”

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s June 2013 issue with the title “Ministry behind bars.”