Paul Simon described his 2023 album, Seven Psalms, as “an argument I’m having with myself about belief or not.” In promoting the album, he spoke of how the project came to him in a dream. A voice told him, “You are working on a piece called Seven Psalms.” He got out of bed and wrote those words in a notebook. The voice returned again and again, feeding him lyrics.

Lyrics have come to him in a dream state in the past. When he was 21, “a vision softly creeping / Left its seeds while I was sleep ing.” He knew “The Sound of Silence” was something special. On the strength of that one song, he got a record deal. But the album, released in 1964, didn’t spark sales. He went to law school in Brooklyn, N.Y., dropped out, went to London to become a folk singer, and recorded another album, which also sold poorly. “The Sound of Silence” became a modest hit on college radio. The record company remixed the song, from a plain folk ballad to the now famous poppy earworm.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

By January 1966, Simon, along with his childhood pal and singing partner, Art Garfunkel, had the top single in the United States. For 60 years, he has continued to listen in on his dreams, to have endless conversations about belief, love, purpose, meaning, doubt. Raised in a Jewish home in Queens, N.Y., he says of himself, “For somebody who’s not a religious person, God comes up a lot in my songs.” He has played out the anxieties of his age, sharing the hopes and fears of his generation, all the while with “reason to believe / We… will be received / in Graceland.” He is a poet who expresses despair while seeking hope.

Simon, 82, is also the subject of a substantial new documentary, In Restless Dreams, directed by the award-winning filmmaker Alex Gibney. The three-and-a-half-hour film jumps episodically to some select highs, and lows, in Simon’s life and career. A first marriage and divorce are barely noted. Too much time is spent on his marriage to the Star Wars actor Carrie Fisher. Several albums and hit songs are never mentioned.

After establishing the dream inspiration for Seven Psalms, the film follows Simon on a journey, in and out of the recording studio, as he seeks the intricate sound for the album. The words may have come from the muses, but the music still has to be made.

In interviews, discussing his work and his relationships, Simon seems soft-spoken. In the studio, however, chasing a sound or a tone playing in his head, he is meticulous. This is an artist at work, making music out of ether. Scenes of him in his studio, surrounded by many instruments or working with other musicians or choirs, show him following an idea that his collaborators can’t hear. He asks a singer to repeat a phrasing, a musician to try a note. He’s an old man now, famous, respected, and those working with him trust him. Though every now and then, there’s a look that suggests they aren’t certain as to what is happening.

More on Broadview:

- How expensive music programs are stunting students’ education

- New documentary explores intimate connection between grief and art

- Joy Kogawa calls new poetry book her ‘last hurrah’ at 88

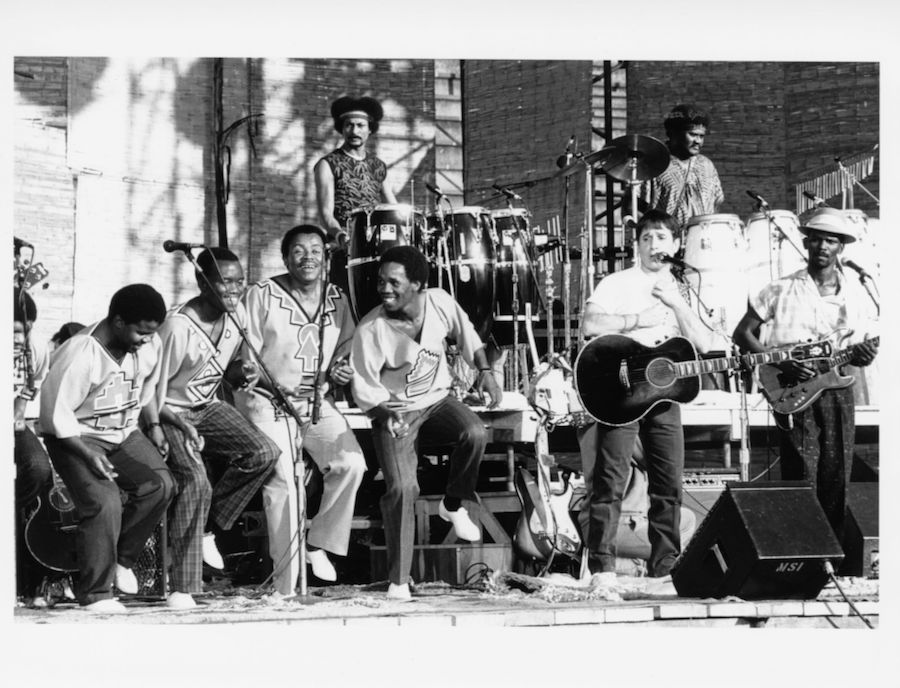

That look is common during the making of Graceland in the mid 1980s. Archival footage of Simon in South Africa, meeting street musicians, singers and dancers, is fascinating. He seems to lead from behind, listening to the locals, following their complicated beats and rhythms.

Mixing traditional American styles (zydeco, country, blues) with traditional African styles (Zulurooted a cappella, drum beats) and his angsty lyrics, Simon created a strange hybrid. “Why am I soft in the middle? / The rest of my life is so hard” he muses on the single “You Can Call Me Al” over a funky soundscape. The despair is in the words; the hope is in the music.

Simon is oddly apolitical for a singer-songwriter of his era. South Africa at the time was under international censure for its oppressive apartheid regime, but he was not there for any ideological reasons. He was there exploring the music, just as his previous albums had explored reggae, ska, gospel, folk, country, rock, Peruvian folk and many other musical traditions.

In extended scenes from a 1987 concert in Harare, Zimbabwe, Simon, then 46, sings his midlife woes while Black South African artists Ray Phiri, Bakithi Kumalo, Hugh Masekela, Miriam Makeba, known as Mama Africa, and the men’s choir Ladysmith Black Mambazo lead a crowd of about 20,000 people from across southern Africa as they dance, laugh and sing along. The lyrics moan as the music moves the body.

The Harare concert did have anti-apartheid calls, which are not in this documentary. Instead, it uses the concert footage to push back on the accusations that Simon was violating a United Nations cultural boycott against South Africa, and more recent criticism that he committed cultural appropriation. The largely but not exclusively Black audience, some of whom travelled from South Africa, and the dozens of Black musicians onstage undermine these claims. Blacks and whites love the music, the film implies, and that’s all that matters.

In Restless Dreams, subtitled The Music of Paul Simon, is not a critical analysis; nor is it about the music. It is a sweet bit of legacy maintenance, much like The Beatles: Get Back. In the end, though, legacy is meaningless if there’s no art.

Paul Simon is a musicians’ musician — a craftsman. He is attuned to inspiration, which sends him on a quest to find a sound. In 1969, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” also came to him from the muses. He knew it was the best thing he had ever written. He thought of it as a “small hymn.”

The documentary does not delve into the making of that song or the album of the same name, even though it was over this period that Simon and Garfunkel came to an end. Simon was the song; Garfunkel was the voice, lifting the melody to the heavens. The boyhood friends who listened to the Everly Brothers after school couldn’t survive success. They grew apart, resenting each other for various reasons. Simon has said it was a matter of musical taste.

They split; they weren’t yet 30. While their friendship has never recovered, Garfunkel returned to sing on the Grammy-winning album Still Crazy After All These Years and again for The Concert in Central Park, recorded live in 1981 in front of half a million New Yorkers. They’ve also done several tours over the decades, including one with the Everly Brothers.

In the half-century since he and Garfunkel parted ways, Simon has travelled to South Africa, Brazil and across the United States, looking to find the sound, the voice, for his songs. Despite losing hearing in one ear, the craftsman continues to chase the elusive music playing inside of him. It is through this pursuit that he has nurtured some hope amid the angst. As he sings in one of Seven Psalms’ many tender prayers: “The garden keeps a rose and a thorn / And once the choice is made / All that’s left is / Mending what was torn / Love is like a braid / Love is like a braid.”

***

Andrew Faiz is a writer in Toronto.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2024 issue with the title “Music of the Ether.’”