Is it possible that the church — mirroring society in general — is wasting a key natural resource? At least one significant segment of the population seems to think so, and its view is supported by a recent study from the University of Waterloo.

The resource is wisdom. And the demographic cohort traditionally dubbed wise — the elders — believe that they indeed have grown in wisdom over their long years, but that the rest of society is squandering this resource. It’s a challenging issue, partly because even a definition of wisdom is somewhat elusive, and partly because this slippery concept is difficult to examine scientifically. So it’s hard to know if the idea that wisdom increases with age is demonstrable.

Igor Grossmann, an assistant professor at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, has taken on the challenge, conducting studies specifically related to wisdom and aging. His findings? To reduce years of work to a few sentences: in North America, yes — people tend to become wiser as they age. His goal is to understand the processes that enable people to think and act wisely.

“I explore how age, psychological distance and social orientation influence emotion regulation, reasoning, well-being and wisdom — integrating these processes in a broad socio-cultural context.” His research method is to study people’s decision-making in “meaningful real-world situations.”

But first, what exactly is wisdom? My informal survey of half a dozen church members in their 70s and 80s and the same number from a youth confirmation class found that old and young were pretty much in agreement: wisdom means “good judgment,” “accumulated learning,” “insight,” “discernment,” “common sense,” “balance” and “making the right decisions.”

A teenage boy says, “Wisdom is not just someone who knows answers to questions, but who can actually apply things they learn in their life, every day.” A woman in her mid-80s says, “Wisdom is what you learn in life, with common sense, compassion and the love of God and your fellow man and woman.”

A more precise definition comes from Vivian Clayton, a renowned geriatric neuropsychologist from Orinda, Calif. Interviewed via e-mail for this article, Clayton states, “Wisdom, as an ability or skill, reflects the integration of three elements: a fundamental level of knowledge (i.e., one does not have to be a genius — just cognitively intact), a reflective ability (as opposed to impulsive) and compassion. Wisdom is evoked in situations requiring decision-making.”

Grossmann, whose study was recently published in Psychological Science, argues that the western world’s view of wisdom is skewed. He blames ancient Greek philosophers such as Plato, who contended that wisdom is a rare trait, a gift that cannot be learned. “Flawed,” declares Grossmann. His studies show “it is not true that it is rare,” nor is it true that wisdom cannot be gained.

Grossmann’s work focuses on “the reasoning components” of wisdom, studying not only what people value but “what they actually do in difficult situations . . . in uncertainty, under threat, in a crisis.”

In his experiments, he presented his subjects with various decision-making scenarios. Then, he assessed their responses in five categories: willingness to seek opportunities to resolve conflict; willingness to search for compromise; recognition of the limits of personal knowledge; awareness that more than one perspective on a problem can exist; and appreciation of the fact that things may get worse before they get better.

Grossmann’s studies quantify responses in those categories. His findings indicate that North Americans do get wiser as they age — at least, according to his reasoning-based definition of wisdom. Twenty-five-year-olds averaged 45 points on his scale; 75-year-olds, 55.

But age and wisdom are not always synonymous; there are plenty of reasons that older people don’t grow wiser. One of Grossmann’s decision-making scenarios involves one-time marital infidelity. Some subjects were told to imagine themselves as a spouse whose partner had strayed. Others were told to imagine themselves as a friend advising a spouse whose partner had strayed. People in the third-person “friend” role responded in ways that would be seen as wise. People caught in the egocentric role of injured party were far less likely to look for solutions. Conclusion? “Egocentricity inhibits your ability to reason wisely,” says Grossmann.

Clayton agrees that although life’s obstacles, tragedies and crises present us with opportunities to grow wiser, it doesn’t always happen that way. “An impulsive person might never quite make the mark because the complexity of decisions requiring wisdom benefit from the passing of a certain amount of time to allow the filtration of important from unimportant to occur.”

She underscores her point: “Age and aging alone does not guarantee that someone will respond wisely. I have met many foolish elders and been in awe of the wisdom of certain people in their 20s.”

So what — besides age and the life experience that comes with it — can help a person grow wiser? Going back to Grossmann’s cheating-spouse scenario, he suggests getting into the habit of looking at life’s problems from a third-person perspective. In other words, faced with a difficult decision, ask yourself this: If my friend was in this situation, instead of me, what would I advise my friend to do? “You can change [your] reasoning very quickly,” Grossmann says. “Reasoning is very malleable.”

Grossmann has carried out some preliminary studies that should catch the attention of the church. In cautious academic language, he says his findings indicate “that the mere effect of being in a mentor or adviser’s role, over time, seems to be promoting forms of reasoning that have been associated with wisdom.”

Being a mentor, in itself, can make you wiser? Probably. So can being part of a community — including a church. “By being in a community, you have a great chance of developing reasoning strategies. You’re more likely to look at the world [from] a third-party perspective,” he says.

All told, growing older usually makes you wiser. But according to Clayton, in many western civilizations, “the attribute of wisdom inspires, but does not drive or inform societal decisions.” We may honour the wise. We just don’t listen to them.

That comes as no surprise to the elders I interviewed. “I don’t think my wisdom and that of my peers is well utilized,” says a woman who has held significant leadership roles in her community. And that’s a mistake, she argues: “We need to keep learning from the past.” Another woman writes, “Sometimes I think seniors are ignored in our society. It’s hard to keep up with all the new things in this world, and some older people feel left behind.” It’s worth noting that this woman in her 80s responds on her iPad to a question sent via Facebook.

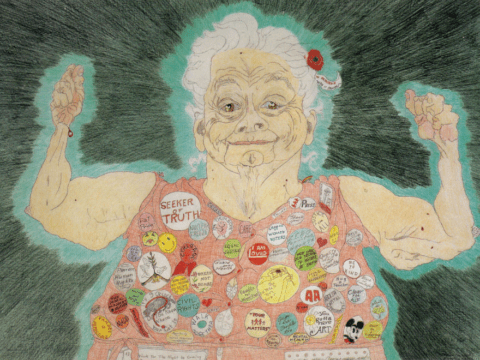

A retired United Church diaconal minister is more optimistic. “It’s getting better. There was a time when more mature folks were relegated to the sidelines. Now, there’s been a shift in attitude and older people are asked to bring their wisdom and insights to issues of the day. Our generation has developed a confidence and feistiness in looking after its own needs. Many are influential and outspoken advocates, especially for those who lack a voice.”

I asked both teens and elders to name people they thought were wise. Some from each group opted for well-known examples: Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu, Mother Teresa, Gandhi. Others, again representing each group, also nominated people from their own circles: ministers, community leaders, “the elders of our church.”

The latter came from a 14-year-old boy. According to Grossmann and Clayton, he’s on to something. Many of the older members of our churches have accumulated wisdom — both the capacity and the ability to act on it — over their years of life. They’ve honed their third-person reasoning skills by living within the community of the church. They are well equipped to be mentors and advisers — and by happy coincidence, being put in these roles will make them even wiser.

Clearly, a resource not to be wasted.

***

This story first appeared in The United Church Observer’s July/August 2014 issue with the title “Older and Wiser.”