Felicia Watkins wasn’t always an atheist. The rhythms and rituals of Catholicism shaped her early childhood: baptism, first communion, attendance at Catholic school. Her mother is Catholic and raised Watkins and her older siblings in the faith.

But her parents divorced when she was six, and she started to have doubts. She prayed for her parents to get back together. It didn’t happen. At eight or nine, when she had switched to a public school and had close friends who were Muslim and Jewish, the doubts intensified.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

“I was starting to question tons of things that weren’t readily tactile for me, that I couldn’t prove,” says Watkins, now 35. “When I felt maybe my prayers weren’t being answered is when I really started to question it.” By the time she hit high school, “I was pretty decidedly a non-believer,” she says. Watkins, a public servant who lives in Toronto, is one of the growing percentage of Canadians known as “nones.” These are the people who check the box “no religion” when asked on the census form which denomination or religion they belong to. Statistics Canada’s 2021 census found that almost 35 percent of Canadians filled out the census that way, up from just four percent in 1971.

In other western countries, the non-religious trend is also pronounced. Nearly 37 percent of people in the United Kingdom, for example, now describe themselves as non-religious. Even the United States, which has traditionally been a nation of strong believers, is quickly catching up at almost 30 percent of the overall population, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center published earlier this year.

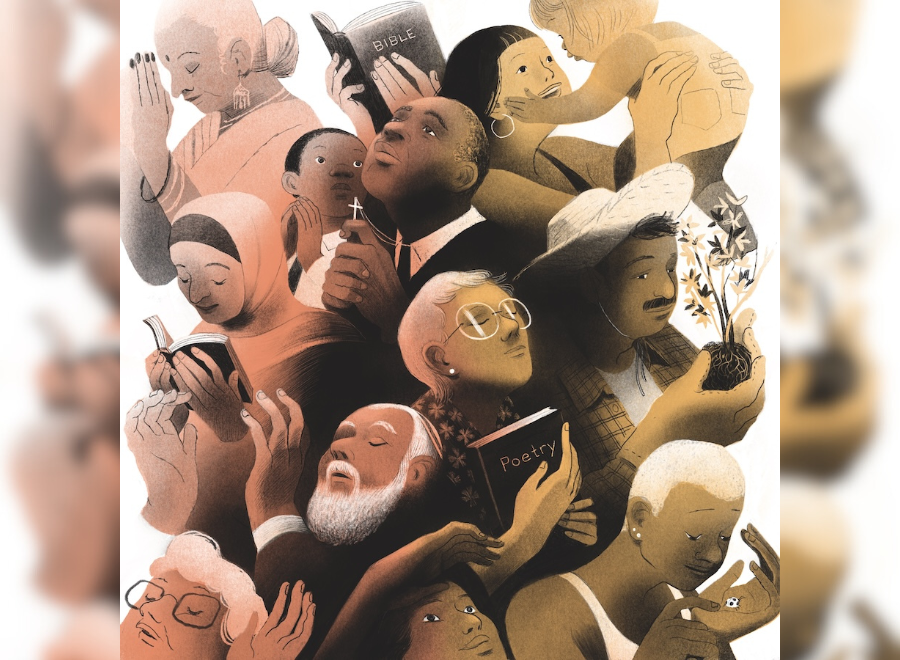

By tradition, and even by name, this group has been defined by what its members don’t believe and don’t do. “The stereotype persists — that nones don’t believe anything, that their unwillingness to affiliate means they don’t contribute to society, that their spirituality is a do-it-yourself hodgepodge designed for their individual satisfaction,” Barbara Brown Taylor, public theologian and bestselling author of Leaving Church: A Memoir of Faith, says in an email interview.

But new studies are beginning to dig deeper — and are excavating some provocative findings about the spike in disaffiliation. Lori Beaman, Canada Research Chair of Religious Diversity and Social Change at the University of Ottawa, is the principal investigator on an ambitious study charting the social impacts of the dramatic rise of non-religion across 10 countries. Her team is turning the myths about non-believers on their heads. “Morality and values have never only come from religions. But for some reason, there’s this narrative that once upon a time, there was religion, and everybody was part of that…and then all of a sudden that changed.”

She says no part of society will remain untouched by the growth in the group’s heft. How we think about and practise everything from law to palliative care will be transformed. Already, social conventions ranging from how people get married and buried to how they imagine the human relationship to the environment are undergoing revolution. “It’s a major social shift, and it has potentially major implications for all kinds of reasons,” Beaman says.

But who are the “nones”? What’s driving the trend? And why now?

More on Broadview:

Millennials are major players. Roughly half of this generation, those born between the mid-1980s and the early 2000s, have no religious affiliation, according to Statistics Canada’s 2019 General Social Survey. These are the children and grandchildren of the baby boomers. Why have they opted out of religion? It’s the epic saga of modernity. “We’re just not the same society as we were at the turn of the 20th century,” says Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme, a professor of sociology at the University of Waterloo whose expertise is the rise of non-religiosity among millennials.

For example, Canadians born in the 1930s to parents who weren’t religious — and yes, they did exist — were likely to adopt a religion as adults. At that time, most non-religious people would meet and marry people who went to church and who would insist that their partners go with them. But for Canadians born in the 1980s, it’s precisely the reverse. If they are raised with religion, they’re likely to reject it once they leave home.

“You’ve got this double whammy,” says Wilkins-Laflamme. “People who were raised non-religious stay non-religious, and people who come from a more actively involved religious background — many of them disaffiliate.” In other words, she adds, “It’s almost like being non-religious has become the normal default.”

Watkins is an example of the trend. While her mother was, and still is, a practising Catholic, as the child of a non-religious dad, Watkins had a strong statistical likelihood of eventually becoming a non-believer. While her dad’s skepticism was a huge influence, Watkins’s doubts dialled up when she contemplated her own faith against the backdrop of her friends’ religious beliefs. “How could my friends be wrong?” she remembers wondering.

Again, Watkins’s experience reflects larger currents in society. Encounters with religious diversity can shake up people’s beliefs and even recalibrate them, says Stephen Bullivant, author of Nonverts: The Making of Ex-Christian America. “You suddenly know a whole different sort of people,” he tells me in an interview. “It opens up possibilities of encountering other world views or arguments.” A space unfolds for inner wrestling, often followed by renegotiated perspectives.

Bullivant cites the internet’s role in creating opportunities to meet new people, encounter new perspectives and do things differently. It’s also forced a global reckoning with church abuse scandals that were earlier covered in one-off stories in the local papers, he says. The potential for almost instant communication with people on different paths has led to a mass exodus from religious sub- cultures — think Mormonism in places like Utah and Alberta — in small towns especially. “The internet opens up this world of close relationships with people who aren’t of the religion you are,” he says. Online spaces also offer a realm for non-religious people to find community and identity.

It’s more complicated than just the internet, of course. “There’s not just one thing going on,” Wilkins-Laflamme says. “It’s not that the internet showed up and everything changed.” Even more influential in this ongoing reformation than the endless menu of activities is a fundamental shift in values. The current zeitgeist puts a premium on personal independence, which means more scope for individual decision- making. “You hear it in how parents are talking about how they want to raise their kids: ‘I’m going to give them all the information, options, and then they can make an informed choice,’” Wilkins-Laflamme says. People opt out of church easily, with no social stigma or feeling of shirked filial duty — and that has been the pattern for some time.

Watkins says that her decision to stop attending Sunday mass was easy for her family to accept. Her older brothers and sisters had already quit or questioned religion before her. “There wasn’t much of a reaction,” she says.

For the many millennials without any church exposure, the choice has often been made for them. There’s no religious identity to reject or rebel against. Instead of feeling angsty, these cradle nones are often just indifferent. “You have to really believe in it or have a real stake in it,” Bullivant says, referring to belief among millennials and gen Z. “And it’s hard to do that if religion isn’t something you’ve been raised with.”

But the drift away from organized religion didn’t happen over only one or two generations. It’s part of a long, tangled history with roots stretching back decades, and it’s more nuanced than just the march of modernity.

***

The trend toward having no religious links can be traced back almost a century. Abby Day, a professor of sociology at Goldsmiths, University of London, and author of Why Baby Boomers Turned from Religion: Shaping Belief and Belonging, 1945–2021, started paying attention to what she calls today’s “little old ladies” in the Anglican Church of Canada and the Church of England, partly to understand why mainline Protestantism has suffered so acutely from religious decline. These are the women who appear devout and do a ton of volunteer work for the church, but have no aspirations for ordination. Day noticed two things: many of these women raised their kids to be respectable church-attenders in the 1940s and ’50s. Their boomer children grew up to become adults who weren’t really present in church, yet these boomers spoke to Day about their mothers’ ambivalence about Christianity and the church. Day’s curiosity was sparked. In the popular imagination, the boomers “did all the ’60s stuff…drugs and sex and everything that nobody apparently had done before. And because of that, they changed everything and became unreligious.” She dug deeper.

She discovered that some of the mothers of the baby boomers were quietly radical. Many had worked during the Second World War and weren’t altogether happy about leaving the workforce. Sure, they had lots of babies afterward, but some communicated subtle discontent to them about society and about church.

While researching her book, Day says her boomer participants told her their Protestant parents took them to church, but that was the sum of their religious activity. “For the most part, religion wasn’t done at home.” Bibles weren’t read, God wasn’t talked about, and, perhaps most significantly, all religious education took place, for the first time in history, exclusively at Sunday school — which consisted of a lot of colouring sheets. It added up to tacit permission to leave the pews.

The social stew in which boomers and their mothers were marinating had other ingredients that likely contributed to the move away from religion: the creation of the United Nations, revelations about the Holocaust and the threat of nuclear war. These things, Day says, created an awareness of difference and equality. Meanwhile, the kids went away to university, dropped out of church and often didn’t go back.

Seen through this lens, millennials didn’t invent the values of personal choice, independence and authentic experience; they inherited them. Millennials and gen Z, she adds, are often dismissed as the snowflake generation for their kinder, gentler values and concern for the environment, but they “were raised [by boomers] with these ideas, and now they’ve taken them and run with them in a way that the other generation didn’t quite get to, but certainly, I think, planted the seeds.”

***

So what do nones stand for? Well, there are the myths. Some of them contradict each other. One is that all nones are atheists, like Watkins, while another is that they are all deeply spiritual, having been liberated from the burden of organized religion. In fact, the label is shorthand for a large swath of people, says Beaman, some who identify as atheists, others as agnostics, some as spiritual but not religious and others as indifferent.

Despite the stereotypes about each one of these stances — atheists, in the popular imagination, are cerebral; agnostics are indecisive, and so on — the myths could more accurately be thought of as a mirror, reflecting back society’s worst fears and highest hopes.

The fears? That non-religious people embody a society that is more consumerist, less connected and less compassionate than in generations past. The hopes? That they represent a more open, more inclusive, less hierarchical future. These hopes are often accompanied by the expectation that the group will save humanity from its excesses, including those contributing to the climate emergency. This dualistic mindset, Wilkins-Laflamme says, also shapes social perceptions of millennials.

In fact, religious and non-religious people aren’t so different as some would think.

Non-religious people do skew white and male — but that’s slowly shifting. Women feel more comfortable now describing themselves as non-religious. “They have their own ways of doing things,” Wilkins-Laflamme says, adding that women tend to eschew atheist meetings that mimic the feeling an structure of a church gathering. And more racialized groups are joining the ranks of the non-religious, too.

“The nature of being non-religious is changing,” Wilkins-Laflamme says, explaining that nones are coming from many more slices of society. It used to be mainly white, university-educated, urban men — perhaps those with the privilege to stake a claim to what was a less-than-desirable identity. Now, as non-religion becomes more normalized, this group as a whole is increasingly coming to resemble the larger Canadian population. “There’s very little difference in rural and urban populations, university-educated versus less-educated populations,” she says.

On measures such as attitudes toward the environment and immigration, meaningful differences just don’t exist between religious and non-religious people — at least according to early findings from a recent survey conducted by the Nonreligion in a Complex Future project, a 10-country research project spearheaded by Beaman’s team. The same holds true in accounts of near-death or extrasensory experiences — no meaningful differences. “As scientists, we want to see the differences; we care about the differences. But sometimes the lack of differences is just as important,” says Ryan Cragun, a sociologist at the University of Tampa and co-investigator on the project.

That’s not to say, he’s quick to add, that religious and non-religious people don’t have any differences in their beliefs and behaviours, or that there’s nothing consequential about the rise of the nones. In fact, there’s a trail of studies showing that non-religious North Americans have distinctly left-leaning views on big divisive issues. They’re more likely to back progressive policies like abortion access, same-sex marriage and universal basic income, for example.

Watkins situates herself “pretty far left” on the political spectrum. “I’m definitely more collective action-oriented, less individual.” Like other millennial nones, she sees gender identity and sexuality as a matter of personal autonomy but upholds community-minded values like higher taxes in exchange for more equitable distribution of wealth. Watkins names housing security as one of her priorities. She often finds herself advocating for her unhoused neighbours sleeping in the lobby of her downtown Toronto condo during the winter months. “I think that’s informed by my own personal experience growing up and having periods of poverty and housing insecurity, but I also think it’s this fundamental belief that all humans deserve dignity.”

How non-religious people make meaning clearly sets them apart from religious affiliates. It’s one of the striking, and statistically significant, differences according to the latest findings. “Many nones and non-religious folks do not see any inherent purpose in life or believe there is a deeper meaning to existence. They do create purpose and meaning, but they recognize that they have created it,” Cragun says. Religious individuals are much more likely to believe that they have a task in life, for example, and to feel that their life has a deeper meaning. But non-religious folks are no less likely to feel that good relationships are the stuff of a happy life. Cragun says that some of the earlier research in the 2000s showing that nones were less connected was “deeply flawed, lumping religious affiliates together whether they attended religious services or not.

If there are so many common threads connecting religious and non-religious people, is the rise of non-religion really a big deal? Actually, yes. Researchers tracing the trend point out that a significant social transformation has accompanied the shift — and more is likely on the way.

“There’s often not much drama associated with it that’s easily visible,” Beaman says. “But when you start to unpack it and think about it more, there are impacts in all kinds of ways.” For one, people are inventing new ways of forging meaning and connection as religious spaces become fewer and farther between. And the new spaces that are rising up to fill their place tend to be less hierarchical, Beaman finds.

Community gardening and nature trekking are just two activities where her team’s research shows this shift in action. People are moving away from the language of human stewardship conventionally rooted in religious traditions — whether they belong to such a tradition or not — while expanding their sense of community. Relationships are turning more horizontal, she says. Humans are no longer at the top, and there’s a more egalitarian vision of the natural world. “Something important has happened beyond the level of the individual. Social institutions have changed and are changing,” Beaman says. She points to legislative changes in recent decades revamping society’s approach to same-sex relations and reproductive rights.

Of all the changes unfolding, some of the most captivating have to do with how death and grieving rituals are being creatively reinvented. Chris Miller, a postdoctoral researcher working with Beaman at the University of Ottawa, has his pulse on how people are reimagining the tradition of the church funeral. “They cover the gamut from ‘I want my body to be buried at sea,’ to ‘I want a music festival [in my honour],’” he says. “It’s a little more tailor-made.”

Remaking rituals isn’t just a non-religious thing. Religious people are doing it too, Miller says. Death cafés are emerging — sometimes in person, often virtual, always informal — where people can talk freely about death without needing to be on the same religious page. “In this space, an atheist who thinks nothing is going to happen [when they die] is able to converse with someone who thinks that they’re going to heaven.”

These cafés are less about coffee than curiosity — and they offer room to respectfully listen to other people’s candid viewpoints. It’s not a debate; it’s just engaging in ideas, he says. In the cafés I attended as part of my research for this story, people often shared their beliefs in a way that rolled off the tongue, seamlessly moving to practical conversations about palliative care and other issues.

Respectful dialogue may become a skill more of us yearn for as the religious base for power and influence shrinks. It’s not clear exactly how that shift toward non-religious pluralism will affect society, but it raises the prospect of growing tensions between opposing camps. If political polarization sharpens, we’ll need more low-stakes spaces for acknowledging competing perspectives.

Millennials are already using their religious and non-religious identities to define who they are — and to create dividing lines. “The non-religious millennial is like, ‘Oh, I’m non-religious, so I’m not like that religious person. I’m pro-LGBTQ+; I’m pro-right to choose; I’m pro-environment; I’m pro-diversity,’” Wilkins-Laflamme says, referring to what she hears from her research participants. “Those are the key issues that they will use to define that boundary between themselves and the religious group.”

It’s no different, and no less dangerous, than the religious millennial, who often uses faith as identity, Wilkins-Laflamme says. Essentially, this generation is weaponizing belief to create a wedge.

Can we continue to co-exist relatively harmoniously in Canada, each of us believing in our own way and doing our own thing? Rising to the challenge will mean resisting the urge to throw up the barricades — to plant flags, whether religious or secular-striped — long enough to preserve the complexity and common ground we cherish.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer and editor in Guelph, Ont.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s July/August 2024 issue with the title “Meet the Nones.”

We have more “nones” now because we don’t need God.

Those who were alive in the thirties saw or experienced two World Wars, a global depression, and the light revivals of the late 1940’s. (Think Billy Graham)

Today a majority of “Westerners” have a full belly, a roof over our heads and peace. Why do we need a deity?

This also explains our moral degeneration, we’ve let go of set societal values. It’s all about me, not about us.

As a belated foil to Gary’s comment:

One of the common misperceptions Gary and other devoutly religious people have is that atheists and other “nones” have no societal values, that it’s an everyone-for-themselves mindset where kindness and collective interest simply fade away.

Many atheists, myself included, think it’s important to have a public value set in place. We just want those values to be based on common interests and evidence, not pure ideology. I think it’s wrong to kill, steal, and deceive, among many other things; but I also think it’s wrong to deny rights to LGBTQ people, and to bar abortions before the point of viability.

As I’ve heard said: if the main thing stopping you from hurting other people is the promise of heaven (or the threat of eternal damnation), you don’t have much of a moral foundation.