Going to the movies can be an alienating experience when you’re Indigenous. Hollywood films are full of racist tropes, if we’re represented at all. Fortunately, for the last 30 years, Indigenous storytellers have been using cinema to creatively respond to our lives and experiences. More recently, they’ve been turning to the future to better illuminate the past.

Such is the case with Night Raiders, a new dystopian film by Cree-Métis director and screenwriter Danis Goulet. In her first full-length feature, Goulet leans into the emotions of her lead characters to tell the story of where we are, how we got here and where we might find ourselves in a few short decades. The film is part of a recent wave of Indigenous science fiction and horror led by filmmakers and novelists using genre storytelling as a vehicle for big ideas. Their parables of Indigenous experience feel liberating and honest, blending critical insight with fantastical thrills.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

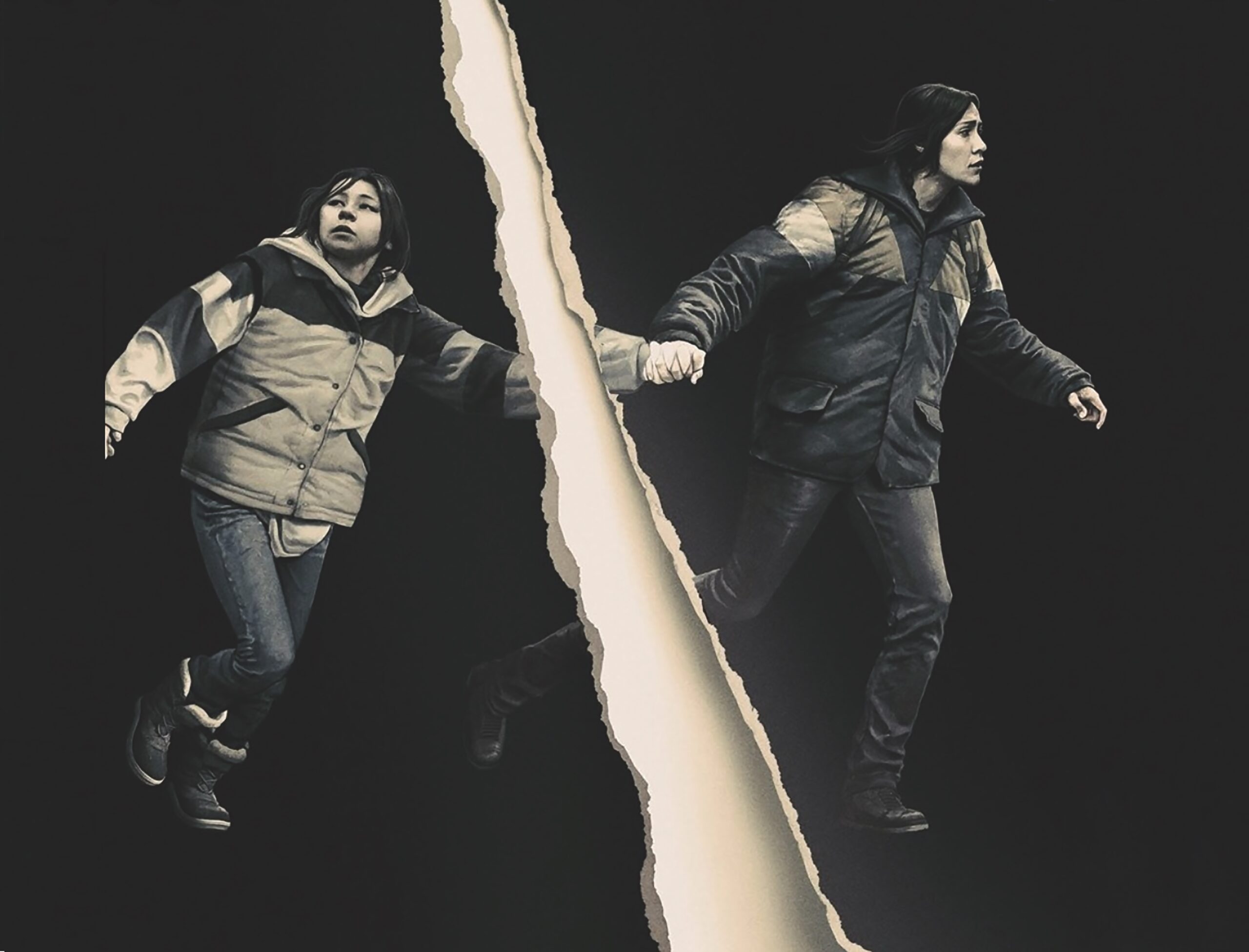

Goulet weaves an understated but consistent dose of sci-fi into her dramatic tale of a doomed future that has been shaped by a civil war upon Turtle Island. The result of that war is that the privileged now live on one side of a wall, and our Cree protagonists, Niska (Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers) and her 11-year-old daughter, Waseese (Brooklyn Letexier-Hart), are forced to exist in an impoverished land on the outside, where resources like food, shelter and health care are scant. It’s a world created by xenophobia, classism, racism and injustice, where oppression nurtures a fight-or-flight stress response in everyone who tries to survive this hostile state.

For five years, Niska has been hiding with her daughter in the bush to prevent young Waseese from being taken by the government, which has a policy of apprehending all minors, supposedly for their “safety” as it prepares for a reconstruction effort. Niska and Waseese are always on the move, trying to elude detection by ever-patrolling unmanned drones. After Waseese is injured, the two search for medical assistance, but Waseese is taken by the state and placed into a children’s academy. Months later, Niska finds herself reluctantly joining a band of Indigenous vigilantes to rescue her daughter and other children locked inside the facility.

In the world of the film, there are forces that have displaced and disenfranchised Indigenous people, and they have done so with indifference. For Indigenous viewers in the present, these caustic and bureaucratic acts of injustice mirror the commonly experienced attitudes of social workers, government employees and law enforcement who wield their sense of superiority as a fact of life rather than a problem to examine. Even as the truth about residential schools is laid bare in hundreds of unmarked graves, some of the most committed apologists for the system minimize the destruction by touting the noble intentions that guided the schools. As Goulet suggests in her story of Niska and Waseese’s separation, this refusal to see through an ongoing whitewash has created the nightmarish, apocalyptic world her characters inhabit.

Kim TallBear, a professor in the faculty of Native studies at the University of Alberta, has written that “Indigenous peoples have been post-apocalyptic since Contact” with Europeans. This shared experience of colonization has allowed Indigenous storytellers to run freely, unapologetically offering observations that can feel uncomfortable for non-Indigenous readers and viewers to digest. As Waubgeshig Rice, author of the celebrated 2018 thriller Moon of the Crusted Snow, explained to me, “I think horror, sci-fi, fantasy and speculative fiction in general are very viable avenues for Indigenous storytellers to illustrate the evils and harms of colonialism. There are many opportunities to use metaphor and contextualize the realities of history through fiction. In that, we’re able to more firmly solidify and convey our experiences for readers who may not be familiar with our survival and how we have resisted genocide, despite the brutal measures of settler colonial governments like Canada.”

More on Broadview:

- How to ensure Indigenous tourism experiences support the right communities

- Residential school survivor documents ‘spiritual journey’ — and the photos are powerful

- Raye Zaragoza weaves Indigenous and environmental activism into her music

The imaginative freedom of horror is a big part of its appeal for Mi’kmaq filmmaker Jeff Barnaby, whose 2019 zombie flick, Blood Quantum, earned seven Canadian Screen Awards. Just as George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead succeeded more than 50 years ago by subtly wrapping his commentary on race relations and social change within the framework of a monster movie, Barnaby takes on colonization in his story of how and why a Mi’kmaq community besieged by zombie invaders is immune from joining the hordes of cannibalistic undead. “One of the things that nobody really talks about with apocalypse films is the almost ecstasy of seeing the powers that be fall,” Barnaby told the entertainment website Vulture.

Indigenous storytelling asks questions about how the world might be different. My own enjoyment of the morbid and macabre seems rooted in being able to identify with the dark, of continuing to live the unsettling realities of being Indigenous in Canada. I’m still haunted by the tragic murder and subsequent inquiry into the 2005 death of five-year-old Phoenix Sinclair, whose family were my in-laws at the time. After the trial, which found her mother and stepfather guilty of murder, I walked around the place by the dump in Fisher River Cree Nation where her remains were found. It was unbelievable to me how a child’s life could end in such a horrific way.

The reality that I find hard to deal with is that all Indigenous people are in some way touched by stories like hers or other personal traumas. In many cases, we know a family who has lived true horror. That I find myself immediately relating to Night Raiders, Blood Quantum and other stories makes sense. It’s a way for me to process a world that is full of terrors.

In Goulet’s future world, the machinations of colonialism never stopped rolling. Its grinding tank treads eat into the earth in search of more land and resources to exploit in a never-ending occupation. But amid the bleakness is a spirit that can’t be crushed, a space of love and acceptance in the community of Elders, warriors and matriarchs who seek to free Waseese. Colonization can’t be put back in a bottle, and Goulet welcomes Indigenous people home to evolve and grow together as roots might, unable to be kept from the sun by a cold, indifferent layer of concrete.

***

Mike Alexander is an Anishinaabe writer and artist from Swan Lake First Nation in Manitoba, now living near Squamish, B.C.

This essay first appeared in Broadview’s December 2021 issue with the title “Familiar dystopias.”