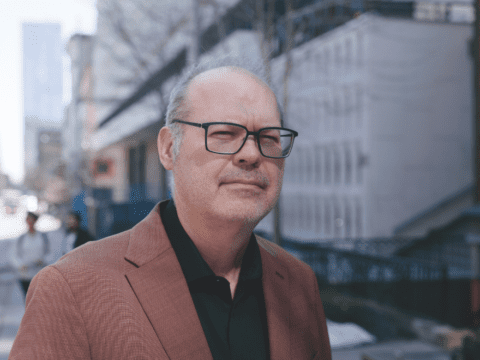

All of us eventually blow up the tidy, arranged narratives of our lives. Or they are dismantled for us. Few understand this as well as Nick Cave. In 2015, the Australian singer-songwriter, frontman of the revered genre-defying band Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, lost his 15-year-old son, Arthur, when he fell from a cliff after taking LSD. Seven years later, his eldest son, Jethro Lazenby, died unexpectedly at age 31. Their deaths shattered Cave. Yet over time, he transformed, his hardened veneer dissolved by grief. To his incredulous longtime fans, Cave has become a religious man making religious music, though hardly in the conventional sense. With his astonishing new album, Wild God, he delivers a dispatch to grieving people everywhere: you can move beyond the devastation. A gazillion caveats, yes. But the beautiful truth, he proclaims, is that there’s life after the cataclysmic event, and it’s a more empathetic, more connected one.

Incredibly, Cave’s latest record brims with unfettered, contagious joy. To listen to it is to feel lifted, carried away, even exultant. I came to this album with my own burden — my 15-year-old daughter had her life forever altered in a devastating accident last year — but somehow, I lay it down with each listening. There’s something sublimely expansive in these songs that sweeps you up and moves you to a better level. And it’s something, strangely, that’s made deeper and more complicated by Cave’s intimacy with grief and suffering. He, together with his Bad Seeds bandmates, has forged a crack where the light gets in.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

The title track, with its gorgeous gospel choir and thrilling crescendo, resembles a jubilant hymn. Filled with fable-like images — a wild God zooms through the city as a “prehistoric bird” — it’s hardly a straight-up religious score. Still, when Cave cries out, in his baritone voice, “Send your spirit down,” the listener feels on the cusp of a spiritual experience.

It’s much the same with the single “Frogs.” Awash in symbols of baptism and renewal, from Sunday rain to the eponymous frogs jumping with joy in the gutters, this track, with its brassy groove and choral harmony, elevates the listener. We’re summoned to a state of awe in a world that just keeps dazzling us with its beauty, for all the reasons it gives us to despair.

Arriving at this album has been a journey for Cave — joy has not, until recently, been where his art has lived. In interviews, he has poignantly described the loss of his son Arthur as a moment of rupture, an annihilating event that demolished the ordered narrative of his life.

Everything changed with Arthur’s death — his sense of self, his view of the world and his approach to making music. His first album released in its wake, 2016’s Skeleton Tree, is fractured and formless. It’s as if the trauma inhabits the songs themselves, especially pieces like “Jesus,” “Girl in Amber” and “Distant Sky.” Written largely before the seismic event but arranged and produced shortly after, the tracks are disconcertingly prescient and enthralling.

But it’s Ghosteen (2019), the first album written entirely in the aftermath of Arthur’s death, that definitively marks Cave’s embrace of a more improvisational style of songwriting. Listening to it feels like a mysterious conduit to the imagined realm of his lost son, with songs like “Bright Horses” and “Waiting for You” conjuring his spirit. And while the band busts up the tradition of the epic song — spurning narrative linearity in a masterful recreation of the chaos of grief — there’s a healing, even holy feel to the music. Liturgical and prayer-like, this is a haunting album that has a deep sacred resonance. So, too, with the recent Carnage, whose soaring, celestial songs like “Lavender Fields” and “White Elephant” make a spiritual impact.

More on Broadview:

It’s a peculiar power that Wild God also holds. As different as this album is — exuberant where Ghosteen is subdued — it, too, is essentially religious in nature. In fact, in making his way back to the world, Cave has returned to church and begun expounding the benefits of a devotional life. Fans who fondly remember him as the angry face of the 1970s postpunk band the Birthday Party are often confounded by this turn. But the 66-year-old rocker — who’s also a gifted novelist, screenwriter and ceramicist — has long been obsessed with God. The early Cave, for all his heroin-infused rage, was inspired by the fire-and-brimstone of the Old Testament. Achieving mainstream success in the 1990s with softer piano-driven ballads, the later Cave found beauty and truth in the Gospels and the figure of Jesus. His love of Christian motifs traces back to his Church of England upbringing and choirboy days.

In recent years, though, Cave has become increasingly vocal about faith. Somewhat cheekily, he’s dubbed himself “religious but not spiritual,” claiming in his remarkable book Faith, Hope and Carnage that “religion is spirituality with rigour” — a clear change of heart for the person who quipped on BBC radio, in 2010, that he believed in God “in spite of religion, not because of it.” His shifting position is rooted in an understanding of grief as singularly transformative.

Cave claims that grief is a kind of heightened state because it brings us to the essence of things. Loss changes us, remaking us in a bewildering process that ultimately returns us to the world with some new knowledge of the fragility and fundamental value of life. What we do with our grief, whether individual or collective, is where change happens: do we let it constrict us, curling tightly around absence, or allow it to expand us?

Cave has chosen to open himself, to find strength in being vulnerable and to connect authentically with his fans, all while acknowledging that arriving at an outward-looking place after acute loss is a slow, gut-wrenching process. After Arthur’s death, he hosted a series of freestyle Q&As with his audience — a total turnabout for a star who once loathed interviews. It’s a format he’s since replicated online with The Red Hand Files, a blog space where he invites fans to ask him anything.

In all these interactions, he moves beyond his once -trademark aloofness and cynicism to articulate his own grief, listen to other people’s stories and just generally approach the world through a loving lens. It’s really something — and it’s moved grieving people the world over.

It’s moved me, too. After my daughter’s accident, I was tempted to embrace the world-is-vile view of Cave’s younger self. This is a view that Cave says he encounters again and again in the letters that come in from grieving parents, and that he has also struggled with. But other people’s gestures of love and tenderness have helped him look at the world differently: as inhabited by individuals always on the edge of catastrophe and in need of compassion.

In a way, Cave’s insistence on being an empathetic, forgiving, understanding person in spite of his suffering is his form of defiance. In One More Time with Feeling, a documentary produced by filmmaker Andrew Dominik in the year after Arthur’s death, Cave admits that his sense of self was something he lost along with his child. He felt he’d failed appallingly in averting his protective parental gaze. His decision, he says, to be happy, to care for others, is his way of resisting the tidal wave of despair that threatens to engulf him.

It’s profoundly relatable. So, too, is his invitation to get revenge on the cruelties of life in the best way possible — by spreading the pure, elemental joy that spills out of the beauty of the world.

***

Julie McGonegal is a writer and editor in Elora, Ont.