When people learn of my unique racial background — I am Algonquin Anishinabe and Syrian — they almost always ask me the same question: “Which side do you identify with more?” To be frank, the question annoys me. I find it’s an attempt to box me in to a singular identity. So I usually answer, “Both. Both sides make me who I am.”

My racial background is complex, but since I didn’t choose and can’t change my ethnicity or the way I look, those things don’t cause me much worry. What I do have the freedom to choose, though, are which spiritual teachings and practices are meaningful to me. Here, I’ve struggled to reconcile the two sides of my heritage.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

I was born and raised in a Syrian Muslim household, and I continue to identify as a Muslim. Growing up, I was aware of my Anishinabe identity, but it didn’t have much influence over me.

More on Broadview: It’s time for Christians to throw in with the working class

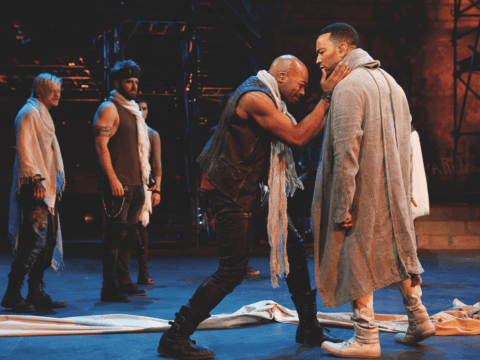

But as a teenager, I began to understand the importance of the Anishinabeg cultural and spiritual resurgence, and I wanted to participate in it. Becoming a father to a young, spiritually curious Anishinabekwe also gave me reason to re-engage with that side of myself. I began to grapple with my spirituality and how I could be a Muslim while also practising and passing down my Anishinabe ceremonies, teachings and values.

That’s not to say there aren’t similarities. Both traditions teach respect for Creation, for example, and both prescribe ritual as a way to connect with something greater than oneself.

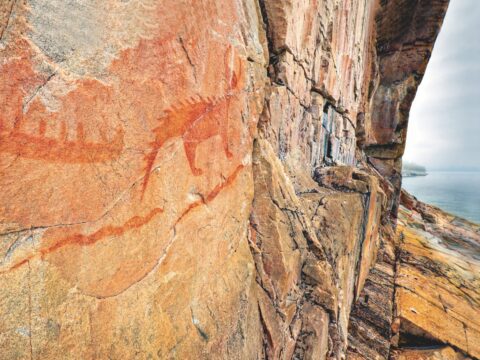

But other teachings don’t mesh well together. The creation stories conflict with one another. Anishinabeg don’t have a concept of heaven, hell or the end times the way Muslims do. And ancestor veneration, which is important in Anishinabe belief, isn’t a feature of Islam (it’s actually forbidden in some sects).

Often, when these contradictions seem overwhelming, I avoid spirituality altogether, or I focus on one side of myself to the exclusion of the other. But this is emotionally distressing; I find myself longing for whatever spirituality I am neglecting.

Choosing is not possible for me. Qur’an recitations and songs in Anishinabe ceremonies elicit the same emotional and spiritual response. Islam is foundational to who I am, and I can’t ignore that. But I also can’t allow my Anishinabe ceremonies and teachings to disappear from my lineage — we must revitalize what colonization took from us. Most importantly, my daughter needs those ceremonies and teachings, too.

And so I’ll continue to live a hybrid spirituality, though even this causes its own distress, since I find myself not fitting into either world fully. I may never manage my two spiritual realities in ways that please those around me, but I will continue to be who I am — Syrian, Muslim and Anishinabe. My spiritual expression will have to be as diverse as my identities.

This column first appeared in Broadview’s April 2020 issue with the title “Both/and.” A previous version used the phrase “ancestor worship.” The word “veneration” was more reflective of the author’s perspective. This version has been updated.

Broadview is an award-winning progressive Christian magazine, featuring stories about spirituality, justice and ethical living. For more of our content, subscribe to the magazine today.