Trekking up the world’s mountains takes money, time and an extraordinary amount of preparation, physical ability and stamina. High-altitude mountaineering tests the skills and resilience of even the most experienced climber, and nowhere on Earth embodies the spirit of exploration and adventure more than the tallest peak: Mount Everest. The motivation for climbers to liquidate their savings, worry their families and risk their lives to summit a mountain varies from ticking a goal off the bucket list to raising awareness for important issues. In the process, many mountaineers reach new heights, not just physically and mentally, but also spiritually. They return to sea level with a much deeper understanding of what is important in life. Here, five climbers share the lessons they’ve learned along the way.

GUIDE

Pasang Kaji Sherpa

The Sherpa people, an Indigenous ethnic group that mainly resides in eastern Nepal and some areas of Tibet, believe the mountains are holy — their peaks are places to be closer to divinity. “Every single mountain, we say is [a] God place,” explains Pasang Kaji Sherpa.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Known as PK, he lives in Kathmandu, Nepal, and juggles a restaurant, mountaineering gear shop, numerous guiding gigs and a family. He has climbed some impressive Himalayan mountains, including Ama Dablam (6,812 metres), Manaslu (8,163 metres) and Cho Oyu (8,188 metres). But when he is referring to the highest mountain of all, which he has summited 11 times, PK reserves the utmost respect.

At 8,848 metres, Everest is the most sacred peak to the Sherpa people. The Nepalese name for it is Sagarmatha, and in Tibet it is Chomolungma. But PK calls it “the mothergod of God.”

Sherpa people were first hired to carry gear to the tops of mountains over 100 years ago because of their adaptation to the high altitudes and familiarity with the Himalayas. In 1953, Everest was summited for the first time by Sherpa climber Tenzing Norgay and New Zealander Edmund Hillary, igniting a global hunger to reach the highest point on Earth and creating a reliance on Sherpa climbers to help them get there.

The job is extremely perilous. Guides like PK trek ahead to install ropes and drape ladders over gaping crevasses, set up camps and carry heavy loads of food, oxygen canisters and equipment, often braving the most dangerous sections of the mountains at least twice as many times as paying customers. In 2018, National Public Radio reported that about one third of those who have died on Everest were Sherpa climbers.

“We work for tourism, but we go for us, too.”

Pasang Kaji Sherpa

Knowing the risk contributes to the respect Sherpas have for the mountains. PK says for any peak that reaches over 6,000 metres, Sherpa guides will ask permission from the gods to climb. They perform a Buddhist puja ceremony, where a monk, or lama, will make an offering of food to ask for safe passage and fortune. “It means I am coming for the climbing. Pray for us. When we are going climbing, we are climbing from the heart.”

PK believes foreign climbers can learn from his culture’s spiritual values. It’s not enough to just want to summit a mountain; you must also be worthy and go forward with respect. Many people push themselves too hard, he says, taxing their bodies to the extreme. “They have to listen to the mountain, how it is, what it looks like, is it safe for climbing? Or is it not?” he asks. “Second, they have to listen to their body, the way it functions, how it works. Can I go or do I have to return?”

Instead, an increasing number of novice climbers with more money than experience are attempting Everest without properly preparing for the ultimate challenge. “Some people come and they don’t have 6,000-metre experience,” PK says. “If they’re going for Everest, they should have done 6,000 metres, 7,000 metres, at least one 8,000-metre [mountain]. Then they can feel how they can breathe, how careful they are and how they have to treat their body.”

Last spring, a picture taken by Nirmal Purja, a Nepalese climber, emerged on social media and almost immediately went viral. The image shows a multicoloured line of climbers packed together trying to summit Everest as if they were at a theme park. Since that infamous traffic jam, the Nepali government announced that any climber hoping to obtain a permit must have already climbed a Nepali peak above 6,500 metres and submit a certificate of good health. But the government will not limit the amount of permits handed out: in 2019, it issued 381 permits, the highest number ever.

Many people in the Sherpa climbing community believe this tourism explosion, while lucrative, has been costly to the mountain. Everest is now home to thousands of pounds of trash, and the surrounding region has been devastated by deforestation, overgrazing and cultural changes in nearby villages to cater to western visitors. PK is worried about the future safety of the mothergod of God — and the climbers: “When people don’t have respect for the mountains, they [have to] give back something.”

MINISTER

Gregg Brekke

For climber Rev. Gregg Brekke, time seems to slow down when he scales a mountain. The act of hiking can be contemplative, with movements linked to breath, and the knowledge that each step brings you closer to the summit. “It’s often very silent, and the only other thing you hear is the wind,” says Brekke, a Presbyterian and United Church of Christ minister who is based in Bellingham, Wash. “I’m getting goosebumps just talking about it.”

As a kid growing up in North Dakota, Brekke read about high altitude adventures in National Geographic and followed the expeditions of mountaineers like Reinhold Messner and Nick Estcourt who made it to the world’s most impressive summits, including Everest and K2. At these high altitudes, where oxygen is thin, it can be difficult to think rationally, so the planning process is essential. “It was always just a fascination with the mental toughness, the preparation,” says Brekke.

He finally “caught the bug” when he moved west to Oregon. That is where he embarked on his first major mountaineering trip to the 3,429 metre-tall Mount Hood in 2013 when he was 43. Since then, climbing has become a form of spiritual care for Brekke, something he has had to cultivate throughout his career. As an ordained minister with a background in journalism, he has held many roles in both ministry and communications. Today, Brekke is the owner of a photography and video production company, and serves as the executive director of the Associated Church Press.

Trekking into the mountains relieves everyday stress and allows him to focus on the immediate safety of himself and fellow climbers, weather patterns and route conditions. He describes a feeling of being refreshed and recharged after a climb, returning home with new insights and patience. “People around me know when I come back from the mountain I’m new,” says Brekke.

“What I feel on the mountain, I didn’t learn from church.”

Gregg Brekke

He is not a certified guide, but enjoys taking friends into the mountains and compares the camaraderie of an expedition to a congregation — with a bit more swearing. The mountain environment, he says, requires a trust, a vulnerability and a transparency that all have to happen very quickly, especially if you’re stuck in a tent during a storm for five days. “You’re going to end up knowing a lot more about each other than if you just see each other for an hour on Sunday morning.”

One of Brekke’s favourite expeditions was in the spring of 2018. For three weeks, he guided a group of four climbing friends up Denali, the highest peak in North America at 6,190 metres. They hauled 50 pounds of gear on their backs, dragging more behind them on a sled. Two climbers were not able to continue past the last major camp because of altitude sickness, but Brekke and the others made it to the summit.

For Brekke, the preparation and the bonds he formed with his fellow climbers were more significant than reaching Denali’s peak. “I think anyone with a little bit of experience would say that summits are sort of fleeting,” he says. “It’s just a moment that you’re there, and if you can’t enjoy the process and the experience, then you’re not going to have any appreciation of the summit.”

Brekke has had to turn back before reaching a peak four times in his climbing career, and he has no regrets. Twice there was a high risk of avalanche, other times he was stopped by limited visibility and high winds. “If you are going to go mountaineering once, to summit one of the more popular peaks and say you did it, it could feel disappointing to not summit on a once-in-a-lifetime trip,” says Brekke. But for regular climbers, turning around because of unsafe conditions isn’t as upsetting. “The point of going to the mountains for me and those I’ve journeyed with is to enjoy the experience and live to come back over and over.”

TRAILBLAZERS

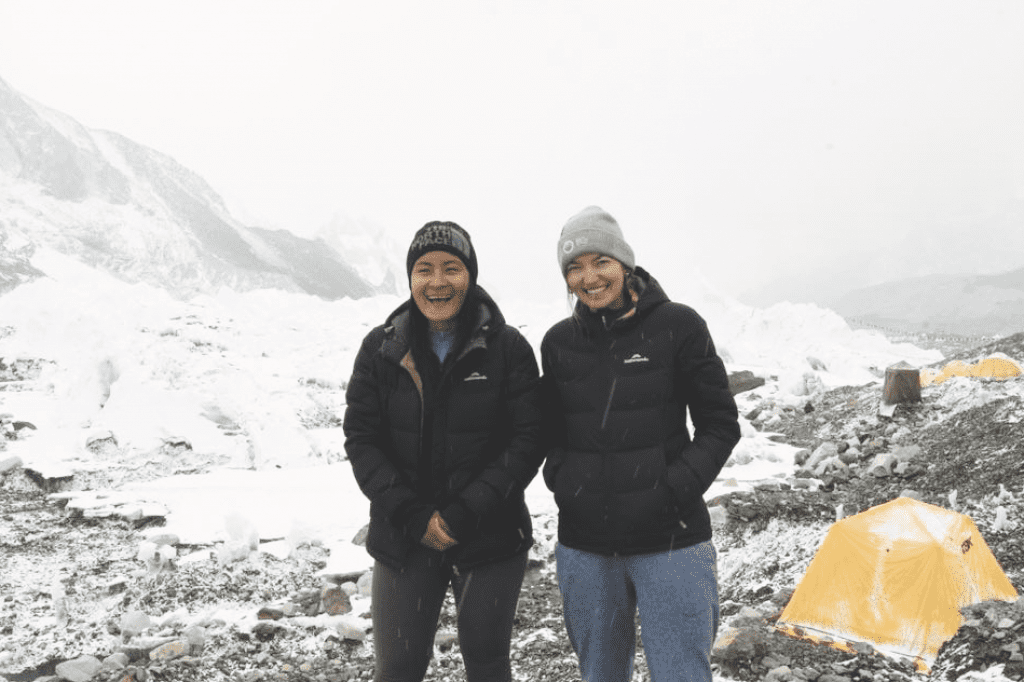

Phunjo Lama & Samantha McMahon

Phunjo Lama and Samantha McMahon are unlikely climbing partners. The two women met in 2015, as Nepal was still recovering from a devastating earthquake. McMahon, who is Australian, had travelled to the country to help in the community. Being a skilled climber, she often headed to an indoor climbing wall in Kathmandu for some practice. There she met Lama, a woman also in her 20s, and the two hit it off. “Samantha was all the time supporting me, saying ‘Phunjo you are so strong, you can do it!’” remembers Lama.

At that time, Lama had just completed her first major climb, up Mount Denali in Alaska, and was emerging as a talented climber in Nepal, despite local norms. She was born in the small village of Chhokangpaaro in the isolated Tsum Valley and spent much of her childhood in the rugged Himalayan mountains, herding yaks with her grandfather. In this small community, mountains are not for climbing, especially for a woman. “In our culture, women always stay inside the house, cook food, wash dishes, and then have lots of kids,” she says.

McMahon encouraged her friend to ignore local stigmas and climb anyway. She was new to mountaineering as well, but believed in its power to teach climbers about themselves. Growing up in Bendigo, a small city in what McMahon calls “the flattest part of Australia,” McMahon became fascinated with tall peaks while backpacking around South America and looking up at the Andes. After travelling to Nepal and meeting Lama, McMahon began mountaineering seriously and returned to the country regularly.

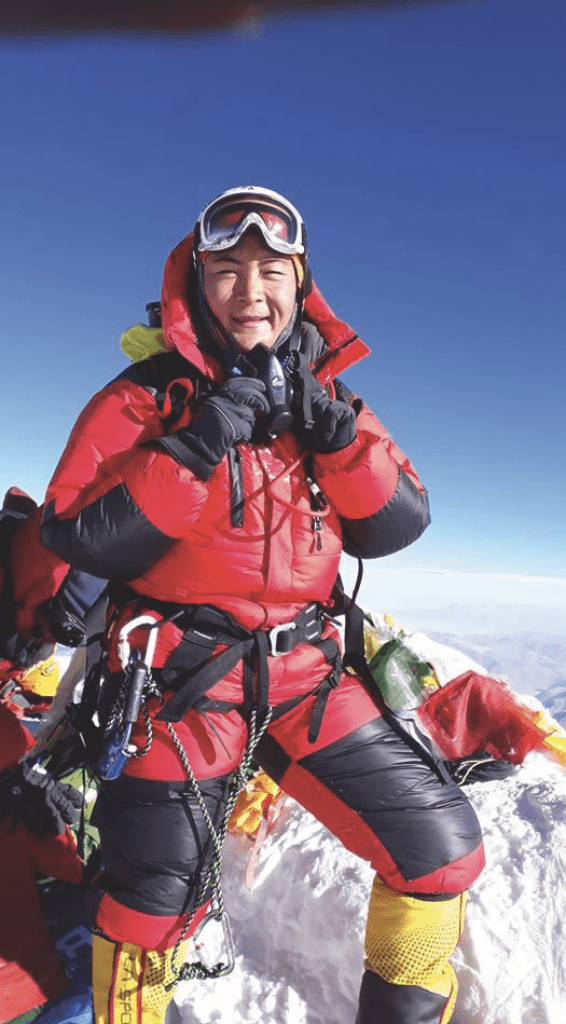

Phunjo Lama atop Mount Everest in May 2019. (Photograph courtesy of Phunjo Lama)

For McMahon, climbing offers powerful lessons in finding strength in herself. In 2008, she broke her leg in a car accident and then broke her hip less than a year later, requiring a complete hip replacement. As a result, the mountains constantly teach her to set her goals higher, despite any physical limitations. “No matter what setbacks you have or what you have to suffer through to get to where you want to go, you can do it,” she says.

In the past four years, McMahon and Lama have become close friends and trusted climbing partners, summiting four or five mountains every year. They started off small and eventually built their way to some of the Himalayas’ most intimidating peaks, including Mount Manaslu, which is nicknamed “killer mountain” by locals because of its high death rate, treacherous icefalls and unpredictable weather.

Through Lama, McMahon began to view the mountains as sacred places, not to be conquered but appreciated, as per Nepali culture. Now, each time McMahon climbs she makes offerings to the mountain, acknowledging and respecting it and asking for blessings for a safe journey. “The scale of the mountains reminds me of how small I am and how mother nature is this big, beautiful, strong force that needs to be respected,” says McMahon, “but, at the same time, it can push us to our absolute limits.”

Now McMahon and Lama are helping young girls in Nepal. They take aspiring female climbers out on expeditions, teaching them how to use the gear, giving them tips on how to speak with foreign tourists and showing them how guiding can be a way of life. As a result, they have helped create a small but growing female climbing community. “It’s another part of adventuring that I really love,” says McMahon. “Seeing the joy on other people’s faces and showing [them that] they can do something that maybe they didn’t think they could.”

Lama and McMahon plan to summit 14 of the world’s highest mountains, all of them soaring above 8,000 metres. In 2018, they reached the frozen peak of Everest. Through these expeditions, they want to set an example for all young female climbers. But Lama has a particular person in mind: her eight-year-old daughter, Tenzing.

Lama, who is a single mom, has made sure Tenzing knows she is equal to any man and wants her daughter to have the freedom to choose her future, something she believes all Nepali women and girls deserve. “We have to find opportunities for ourselves,” says Lama. “Opportunity never comes inside the home. You have to go outside and fight the difficult things.”

HUMANITARIAN

Elia Saikaly

When Elia Saikaly was 26 years old, he received a call from his friend Sean Egan, a human kinetics professor at the University of Ottawa. Egan was heading to Everest, where the 63-year-old health buff hoped to become the oldest Canadian to summit. And he wanted Saikaly, a videographer, to accompany him.

Having never even slept in a tent before, Saikaly agreed to join Egan and record his journey, but only as far as base camp. There, Saikaly trained a guide to carry on the camera work for the actual climb, and he returned home to Canada.

On April 29, 2005, Egan tragically died of heart failure on his way up the mountain. Saikaly was in shock. Egan’s goal wasn’t only to summit, but to use the platform of Everest to inspire people to live happier, healthier and more meaningful lives. And so Saikaly made the decision to honour Egan’s journey by bringing his friend’s ashes to the top of the world.

To fund the expedition, Saikaly sold his car and condo, withdrew all his savings and borrowed money from friends (the average cost to climb Everest is about $45,000). In 2007, with little to no climbing experience and high expectations, he and his friend Gabriel Filippi, who also knew Egan, flew to Nepal with the professor’s ashes.

“There’s much more to it than just climbing a mountain.”

Elia Saikaly

After a gruelling seven weeks, first trekking to base camp and then climbing portions of Everest to acclimatize their bodies and brains, Saikaly and Filippi were finally ready for their summit push. On May 19, they left camp four, the last camp before the summit, and climbed for nearly 12 hours in temperatures as low as -25 C, breathing oxygen from a tank. At this altitude, the oxygen levels are two-thirds lower than at sea level. Saikaly’s muscles were working hard for each step, his mind a whirl of delusion. Climbing a steep narrow path, completely focused on his goal, Saikaly approached the south summit, just 150 metres from the top.

At this point, Filippi, his beard white with ice and small icicles on his eyelids, turned to Saikaly and removed his goggles and mask so he could look his friend in the eyes. “Elia, we will make it to the top of the world, but we will die upon descent due to the change in weather. What do you choose?”

That day, with the summit in view and the ashes of his friend in his pack, Saikaly had to make the decision between survival and fulfilling his promise. It was a pivotal moment. “Everest said ‘no,’ and thankfully I trusted the leadership, and I was humble enough to accept defeat,” he says.

The experience taught him to accept his own limits, especially in the face of nature, as well as his own insignificance — the mountain doesn’t care if you reach the top. But that lesson didn’t come easily.

Broke, directionless and defeated, Saikaly returned home to nothing. He floundered for a time, but then decided to keep climbing, and soon made it to the highest point in North America, Mount Denali, and then Russia’s Mount Elbrus and Aconcagua in Argentina. With each climb, he became stronger and more passionate about making a difference.

In a way, the “failure” of not summiting Everest changed the course of Saikaly’s life. In his teens, Saikaly was a rebel kid, lacking direction. But then he discovered what it meant to be part of something larger than himself. As he said in a TEDx talk: “I started to realize that perhaps these obstacles, perhaps these setbacks, perhaps these detours — perhaps they were gifts in disguise, as a means to propel me in the direction I was destined to travel.”

Saikaly made a decision to use his camera and new-found love of climbing to inspire others, or as he says, “Give something back.” In 2010, he launched an experiential learning program. He hopscotched across the world, climbing mountains while connecting to schools back in Canada via a live feed. He has climbed Mount Kilimanjaro for albinism, travelled through Jordan working with Syrian refugees and visited parts of Africa on humanitarian missions. His hope is to inspire kids by demonstrating the lessons the mountains have taught him: the importance of compassion, empathy and working together.

In the spring of 2010, Saikaly finally made it to the top of Everest with his friend’s ashes. This time, he also brought thousands of students: he went live at camp four and within 100 metres of his goal, he radioed a gymnasium of school children listening from about 12,000 kilometres away in Ottawa.

Although it was an exciting moment, Saikaly believes the real value of his expeditions is showing others what is possible. For him, the driving forces are pushing limits and finding out what you’re capable of and what is important in life. “I think that’s what the mountains teach you, in many ways. If you’re paying attention.”

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story stated that Elia Saikaly climbed Mount Kenya for albinism. He actually climbed Mount Kilimanjaro. This version has been corrected.

This story first appeared in Broadview’s January/February 2020 issue with the title “View from the top.”