‘I didn’t know how to be a Canadian — how to live in a country with a different culture, a different language.’

Edgar Ayala Ventura

Age: 50

Country of origin: Peru

Arrived in Canada: 2014

Attends: Knox United Church

Location: Calgary

Lima was a bit difficult. It’s a Catholic society; I was never out of the closet there. It was a little bit stressful. I come from a very strong Catholic family. In Catholicism, we have a fear of scandals. Most gay people have two lives; it’s very, very difficult to be open in the society. It’s possible, but you will be rejected. Of course, I was very afraid about that. I had my own life hidden, so I didn’t feel completely happy.

I have my family there, with three siblings and my mom. My dad died 20 years ago. I lived with my mom and one of my sisters and my nephew. I studied chemical engineering. I worked many years as an engineer in the private sector and also for the government on environmental problems. My professional life was okay.

The process to immigrate to Canada took close to four years. In that period, my partner, Ralph Zackheim, who is from California, and I decided to marry in one of the countries that legalized gay marriage. We thought about South Africa or Canada. But in 2010 in Latin America, the country that decided to open gay marriage was Argentina. So we married there on Oct. 11, 2012.

For me, everything in Canada was new. I didn’t know how to be a Canadian — how to live in a country with a different culture, a different language. I studied English in my country. But when I came here, I was surprised that people speak so fast, and I needed to study English again.

I was an engineer in my country, but here in Calgary it’s different. I needed to start another thing. I volunteer with Calgary Outlink [a centre for gender and sexual diversity] and was previously volunteering with the Salvation Army. I am learning a little more English. I work in a grocery store, putting away the products on the shelves.

Ralph and I are very happy to be part of Canadian society. We took this like an adventure — our safari in the town. Because it’s new. It’s different. At least for me. One of the reasons I feel better every day is because of both sides of my life. My faith has not changed. I believe in God, and I think God is close to everybody — doesn’t matter if you are gay, lesbian, transgender or heterosexual. On the other side, I continue to volunteer with Outlink because it’s part of my personal effort to understand the people who are different, because in my country I couldn’t do that.

I met many gays and lesbians in my country, but I never defended them. My country and other countries reject people — I feared that, and I want to understand and defeat my fears. Here, I see people who are transgender, or whatever different orientation, and they are part of society. They are part of everything. They are professionals. They are educators. They are fathers and mothers. I need to understand and be clear about that. Here, I have the opportunity to help, especially new immigrants who have different problems from different countries. And they have maybe worse stories than mine.

The church and the LGBTQ community are part of my strength. There are gays and lesbians who attend Knox United Church. I feel comfortable. I don’t need to hide my orientation, and I talk freely with them. Really, I’ve got very good friends in the church.

Of course, I am committed to the church, Knox. We have different groups, and I am involved with a group that wants to help First Nations people through reconciliation with an affirming church. I am part of the group.

My faith in God is increasing every day. Like I always say, if God is close to you, you don’t need to fear anything.

The interviewer, Mario Toneguzzi, is a journalist in Calgary.

‘The cancer has come back. It’s serious. But I have had two lives: one in Japan and one in Canada. I’m so grateful.’

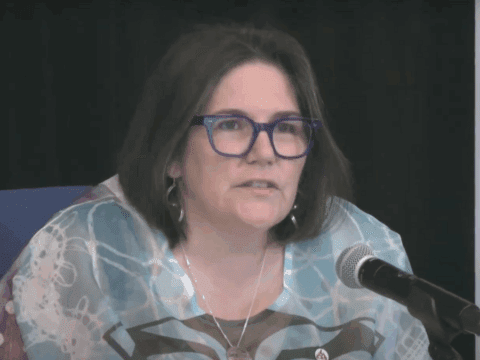

Rev. Yoko Kihara

Age: 53

Country of origin: Japan

Arrived in Canada: 2005

Serves: Gilmore Park United Church as the minister of Christian development and outreach

Location: Richmond, B.C.

Even though there are very few Christians in Japan, there are many Christian schools planted by North American and European missionaries. I received the legacy of that missionary work when I went to a Christian high school and university. Seven denominations in North America founded the Tokyo Woman’s Christian University that I attended because, at the time, there were few postgraduate schools for women in Japan. The missionaries made a great effort to plant educational organizations for girls and worked very hard; some were even persecuted. I was raised with these kinds of stories, and I became Christian. My mother and I were baptized when I was a 20-year-old university student. Some United Church people don’t have a good impression of missionary work, but my impression is very positive.

I got a position teaching language arts in a Christian high school in Tokyo, but I really struggled because it was so competitive. Private Christian schools are very popular in Japan, partly because these schools generally respect the freedom and the independence of students, and are less controlling than local public schools. It’s very competitive. Many students were stressed out. Some of my students were mentally ill. Some dropped out. Artistic students suffered. I couldn’t reconcile the deep gap between the idealistic educational style of Christian education and the reality of the world.

After five years of teaching, I quit my job to study theology. In 1997, I was ordained as a minister of the United Church of Christ in Japan.

My husband and I served a small church in downtown Tokyo. There were so many struggling people there — homeless people and foreign workers from China and other countries. I started to do some outreach work. Nowadays, there is help, but there was nothing then. It’s such a dysfunctional system. I was angry all the time. My husband and I were working together, but his physical and mental health were not good. The church board wanted us to work for the members, not for the surrounding community. They didn’t care about foreign workers. Canada encourages a multicultural and diverse society. That’s one of the reasons I really wanted to come.

In Japan, we have to respect elders, experienced people and men. I was a black sheep when I was in Japan because I tell the truth. They hated to hear a young female minister tell the truth. When I left Japan, I almost lost the meaning of my vocation and where my life was heading. Now I feel that I have some kind of answer in my experience and encounters in Canada.

We came to Surrey, B.C., in 2005. The weather was beautiful. The church people were so nice. Our English was not good, and people were supportive. But it was really tough. In B.C., there are so many strikes. The container truck association was on strike, so we couldn’t receive the boxes I sent. For two months, we had nothing. No dishes or pans. The church people donated a lot. Also, I couldn’t get the phone and Internet connected because the company was on strike. Even the teachers had a strike. I thought, “What’s happening in this country?” In Japan, the bus and train and everything comes on time because it’s a small place with a huge population, and so everything should move. Canadian-born people wait so patiently. I think it’s because it’s such a huge country and the weather is so severe. There are many things we can’t control in this country. I think the patience is a good thing.

I was diagnosed with breast cancer three years ago. I had surgery and radiation treatment. The cancer has come back. It’s serious. I honestly don’t know how many years I have. But usually people just have one life. I have had two lives: one in Japan and one in Canada. I have had so many different kinds of life experiences. I am surrounded by so many good people. I am loved, supported and embraced. I’m really satisfied with my life. I’m so grateful. I wanted to talk to The Observer because I want to tell United Church people how I have been grateful to be part of the United Church even though I was born in Japan, and how much I feel blessed.

The interviewer, Rev. Trisha Elliott, is a minister at Southminster United in Ottawa.

‘The Lord was calling me to come to Canada, but I didn’t actually know which place — and then just the word ‘Newfoundland.’’

Rev. Simon Muwowo

Age: 39

Country of origin: Zambia

Arrived in Canada: 2015

Serves: Burin and Epworth pastoral charges

Location: Burin Peninsula, N.L.

In 1996, I was in secondary school when I started feeling this sense of call to serve the Lord. I was rather at a crossroads, not knowing exactly what I should do in life. But my dedication to the work of Christ started giving me some indicators that I needed to work for the Lord, that I needed to pursue a professional career.

The United Church of Zambia has this tradition where young boys are trained in the nature of Christ using some military concepts. It’s called the Boys’ Brigade, and it was founded in Scotland in 1883. I got involved with the youth boys’ movement, and that instilled a lot of discipline within me and enabled me to take part in the life and the work of the church.

I served the United Church of Zambia for a decade. I was very comfortable. I had a supportive church, which had over 2,000 members, and I established a lot of ministries in the church. Everything was good. If I was made to make humanly choices, I would have stayed. But I felt the Lord calling me to be a blessing to the world. Because of the strength of the call, I followed that command. And I had this sense of call to come to Canada specifically.

I was so drawn to the passionate commitment of The United Church of Canada, whose ministry does not exclude anybody. I had this liberation concept — which no church per se in the whole world has except The United Church of Canada — the concept that talks about liberating people, welcoming people from all sorts of backgrounds. So I felt very connected with the ministry of The United Church of Canada, and I wanted to contribute towards that.

The Lord was calling me to come to Canada, but I didn’t actually know which place. I went online — and then just the word “Newfoundland.” I don’t know if it’s because of the word “new,” but I was really attracted to the ministry here, and I felt this was the place that the Lord was sending me. I obtained a work visa and was granted a work permit that allows me to perform religious duties. I arrived in Newfoundland in February 2015.

The first thing was to contend with the winter! Then, secondly, the culture. In the long run, we have come to understand that Newfoundlanders are very unique people, very welcoming people.

The first three months were very difficult for me. I felt like, “Oh my God, how am I going to make it?” Especially when it came to youth ministry. I come from a country where the majority are young people, and I worked with them and established a key ministry, raised them to do all sorts of work for Christ. Very easy. When I came here, youth were not in the church, and it’s part of my passion to bring them in and to develop a spiritual foundation in their lives. But it was very difficult in the first instance. So I had to break that cultural barrier and was able to get into the life of the young people.

There are two main successes with youth: The first is the establishment of Coffee House Two 52, a youth ministry outreach that connects with young people beyond the four corners of the church. The second is this summer’s month-long youth exposure trip to South Africa and Zambia.

First and foremost, faith has helped me to be a very determined person. I looked at certain characters like Abraham, who was promised that if he followed the way of faith, God would provide all that he needed. I looked at characters like Paul, Moses, Jesus — in their lives, God made the impossible possible. Such characters have shaped me to be a very determined person, a very compassionate person, a person who is not afraid to face challenges regardless of how massive they are — and actually, that’s what has contributed to my successful ministry here on the Burin Peninsula.

I feel I want to stay here in Newfoundland and do the work of Christ. It’s mutual. I feel it, [my church members] feel it. They’ve expressed it to me, and I have shown it to them. I feel, as the Latin words say, vox populi, vox Dei — the voice of the people is the voice of God. I see it to be the voice of God. I feel I want to stay, and stay for a few more years.

The interviewer, Paul Herridge, is a journalist in Marystown, N.L.

‘With the United Church, they welcome you as you are. They don’t say you have to recite these prayers and then you will go to heaven.’

Michael Sandapen

Age: 47

Country of origin: Mauritius

Arrived in Canada: 2014

Attended: Knox-Metropolitan United Church

Location: Moved from Regina to Saskatoon in May

I wasn’t that motivated to come to Canada. It was just an opportunity to see bigger things, to have new experiences and to meet new people, because Mauritius is really small — everyone knows everyone. I thought, “Let’s go on an adventure.”

I landed in Quebec. Then I moved to Ottawa, to Gatineau, to Quebec City, then to Moncton — because my brother was in Moncton. Then he got a job in Nova Scotia. So I had to choose: go to Nova Scotia or go elsewhere. According to the stats, Saskatchewan had a low unemployment rate. I thought if I went to big cities like Vancouver or Toronto, I’d have to compete with so many people. And I was always fascinated by the word “Saskatchewan.”

I thought, “Am I making a big mistake? What am I going to do [in Regina]?” I mean, if you have a family, it’s okay. If you have a good job, it’s okay — you go to your job and then you go back to your family. But, being single, there’s nothing that you can really enjoy. On a Sunday evening, it’s like a dead city. I was like, “Is there an epidemic or something? Is that why everyone is staying at home?”

Je parle français. There isn’t a big French community [in Regina], but there are some. I think there are about 2,000 French speakers.

In Mauritius, I worked in the financial sector and then in the social field. My studies were in economics, law and French. I was working in rehabilitation for drug users and alcoholics. So, from Moncton, I applied for a job with Souls Harbour Rescue Mission [a Christian mission in Regina]. I got the job, and I started meeting people, especially the homeless, because that’s a cause that I really take to heart. I know what it’s like being on your own, having no one to talk to.

Fortunately for me, I met a really good person. He said, “Mike, you know on Sunday we have free coffee at the church.” That’s how I came to the United Church. I’m of Roman Catholic faith, but I don’t really believe in faith things. What I see is human beings first. With the United Church, I’m getting more at ease, because they welcome you as you are. They don’t say you have to be baptized or you have to recite these prayers and then you will go to heaven — which I don’t believe at all. I believe that making a difference in someone’s life is just being human.

What shocked me was the condition that some of the First Nations people are living in. I would not believe that, in a country like Canada, these people are still suffering. That they’re looked down upon, considered useless. I was shocked to see how they were living, how they were forced to live, and the trauma that has been caused. That was the first thing about being here that shocked me.

There are other people from Mauritius here. Saskatchewan’s immigration program wanted people who were skilled in certain fields, like drivers or welders. So people came from Mauritius to work here. Now they’re getting fired. Many Mauritians I know are facing this problem. They are settled, and their kids are going to school, but they’re not sure if their work permit will be renewed. It’s a very stressful situation, and it’s very unfair, because you can’t make people come two or three years for a contract and then say, “Because of the recession, we don’t have enough money, so we won’t keep you anymore.” This is a form of exploitation.

I haven’t joined a new church [since moving to Saskatoon]. I haven’t made new friends yet. My apartment is a bachelor in a basement, so I sometimes feel like a rat. Besides the new job at a bank, I like the river. I was born on an island, so I have always loved water.

My mind is in Mauritius. My body is in Canada. Every morning, I still look at the Mauritian newspapers instead of Canadian newspapers. Maybe that will change. If things get better, I’ll stay, but I’ll always be an immigrant, and Mauritius will always be my country. Deep in my heart, I will always be Mauritian.

The interviewer, Wanda Schmöckel, is a journalist in Regina.

‘Canada gave me the opportunity to explore ideas and learn from people who think differently.’

John and Julie Oh

Ages: 75 (John) and 71 (Julie)

Country of origin: Korea

Arrived in Canada: 1967

Attend: Brechin United Church

Location: Nanaimo, B.C.

Julie: My mother was born in 1915 and went to high school in Seoul, Korea — only privileged girls could. She’s the one who pushed me to go abroad. As soon as I finished high school, I came here by myself. My mother was not afraid to send me to the unknown world.

John: I was born in what is now North Korea. Our family came to the south before the war broke out in 1950. My family couldn’t support me to go to university. So I joined the South Korean army, and I served 32 months. In non-industrialized South Korea, it was hard to find work. I went to Vietnam during the war and served 17 months as a civilian employee of the U.S. Army. Always, I wanted to come to North America to have a post-secondary education.

Canada had a whites-only immigration policy. The Lester B. Pearson government wrote the white paper on immigration in 1966, and the policy began to change. It became colour-blind and based on individual qualifications. It was a turning point.

I came to Toronto in 1967 and went to the immigration department one week after I arrived. They asked me, “Do you want to do your interview now?” That same day.

Julie: On my way to Canada, I had $100 in my pocket. During a stopover in Japan, somebody sitting with me said, “Let’s go to Tokyo!” I went, and I spent $10 to buy a transistor radio — I still have it, and it’s still working. I arrived in Vancouver and got to know about Rev. Sang Chul Lee [who later became a United Church moderator] through a friend. I called Rev. Lee, and we met in downtown Vancouver. He was very kind to me and even invited me to his home in Richmond, B.C. After a week in Vancouver, I travelled to Toronto on a Greyhound bus. The fare was $50. It took three days. I saw the scenery change from Vancouver over the Prairies, into Ontario, past Lake Superior. It was a really, really impressive journey.

Julie: John and I met at Toronto’s first Korean congregation, Toronto Korean United. It started in 1967. The Korean people in Toronto wanted Rev. Wilfred Burbidge, who had been a missionary to Korea, to be the first minister. In 1969, Lee came, and we were one of the first couples he married there. My first job was at the Royal York Hotel in the kitchen as salad girl. After six months, my English was good enough to be a waitress.

John: At that time, every second company had a “help wanted” sign. I had a job unloading petroleum coke [a coal-like fuel] in dusty burlap sacks from tractor-trailers, taking it to the warehouse, up a freight elevator and stacking it. It was a physically tough and dirty job. I did so many jobs like this. One day, I thought maybe I should go back to school.

Julie: We never had the time to feel sad since we came here. We were too busy moving ahead.

John: With a post-secondary education in the 1970s, if we had gone back to South Korea, we could have done better financially. It was rapidly industrializing and needed people with English proficiency. Personally, I don’t think I have any regrets. Life is more than making a living. Canada gave me the opportunity to explore ideas and learn from people who think differently. When I go back to South Korea, even though Seoul is much bigger than Toronto, people there are very closed-minded. It has really been important to me. I wouldn’t exchange that for a million dollars.

If Americans start a war with North Korea, the whole peninsula will become ash again. I’m hopeful that Korea will become unified again — like Germany. No one would have predicted that would happen.

John: We became elders in that first Korean congregation. Much later, in 2002, I served on the Toronto Conference anti-racism task group, and on the [General Council’s] 2007 review of partnerships with sister churches in foreign countries.

Julie: We’ve been married for 47 years. We were very poor students. There was no honeymoon. So now, whenever we travel abroad, we say, “This is our honeymoon.”

I think we are in a partnership, rather than in the Korean traditional hierarchical form of keeping women low and subservient. Both of us arrived here and got educated. I never took time off except three months of maternity leaves for our two children. I worked a solid career as an accountant, and John worked as an economist, and we are compatible in supporting each other.

The interviewer, Pieta Woolley, is a journalist in Powell River, B.C.

‘I opened the heavy door and saw people from all around the world sitting in pews waiting for the service to start. It was amazing.’

Damber Khadka

Age: 43

Country of origin: Bhutan

Arrived in Canada: 2009

Attends and serves: Knox United Church as pastor for the Nepali ministry

Location: Winnipeg

My people live in southern Bhutanand are of Nepalese origin. Our ancestors migrated from Nepal to Bhutan around the 16th century. In 1989, the ruling party of Bhutan adopted a policy of “one nation, one people.” They began to carry out ethnic cleansing against us, arresting people and torturing them. The Bhutanese government told the Nepali-speaking people to leave the country or they would send their armies to our villages and burn our houses. We were so scared. My family members were well-established farmers. We had cattle, sheep, goats and chickens. We grew rice. We left everything behind.

I was 18. It was January 1992, and it was very cold outside. Most of the people had already left the village. There were a few of us still living in terror. We couldn’t live that way any longer. We left in the middle of the night. We walked for hours to the border of India. We crossed at midnight and spent the night under a tree. We had no destination, no plan. We wanted to save ourselves from a terrible death, that’s all. The Indian army took us to Nepal, and we were put in a refugee camp. At first, there were no aid agencies there. We had to survive by visiting the villages and begging for food. After four months, the [U.N. Refugee Agency] started looking after our basic needs, and life became a little bit better. We lived in that camp for 20 years.

I got married there. I was just 21, and my wife, Sumitra, was 16. I was Hindu, and she was Christian. We knew our parents would not allow it, so we eloped. We left the camp for a few days and stayed with my cousin. When we came back, our families would not accept us. Eventually, I became a Christian. The expectation was that the wife would convert to the religion of her husband, but I chose to convert to my wife’s faith. My family closed their eyes and refused to include me. We made a hut, and we started living there. The next year, we had our first child. It took a while for our families to understand. We just insisted on what we believed, and finally they had to compromise.

In 2008, some nations opened their doors to Nepali-speaking refugees. We were thrilled. Now we had hope. I chose Canada. I could see it had a multicultural society where people were living in harmony, respecting each other’s cultures and traditions. I talked to my family, and everyone agreed. Most of my family came to Canada except for one brother who lives in New Zealand and one sister in the United States.

We came to Winnipeg in 2009. On the first Sunday, I told my family, “We don’t know the streets, and we might get lost, so you stay home. I’ll find a church, and next Sunday you’ll go with me.” I walked up the street, and there was a huge building in front of me. I didn’t know it was a church. I thought, “How about if I just go inside and see?” I opened the heavy door and saw people from all around the world sitting in pews waiting for the service to start. I had never experienced that before: people from different ethnicities coming together under the same roof to receive the Lord. It was an amazing experience for me, and at that moment I felt I belonged to this place.

I started a ministry in Nepali at the church. At first, it was just our family. Now we are over 80, all from Bhutan. Initially, we had many challenges. We were all new to this land. But we shared our experiences. I was not a licensed minister, but I volunteered, providing support to my community. Now I serve as a lay minister for the intercultural service and as a full-time pastor for the Nepali-speaking ministry. My job is not limited to managing the worship service. People come to the minister if they have questions regarding law or immigration or anything that requires interpretation. I don’t know if that’s the job of a minister, but sometimes we have to go beyond that. In the beginning, we needed this church. Now this church needs us.

The interviewer, Josiah Neufeld, is a journalist in Winnipeg.

‘The life I’m living in Canada is what I dreamed of. Many people are dreaming like this back home.’

Adebayo Katiiti

Age: 22

Country of origin: Uganda

Arrived in Canada: 2016

Attends: St. Paul’s United Church

Location: Edmonton

I’m Adebayo Katiiti, a trans man from Uganda and a refugee protected citizen in Canada, and a sportsman. I love who I am, and I love my life.

I do all the swimming strokes, but my best stroke is butterfly. I do it with passion and love. It shows who I really am. I also play soccer; I was on the Ugandan national team. I play handball. I play floor hockey — not ice hockey [laughs] — tennis, badminton, basketball, field and track athletics. The passion of the game, the competition, the attitude — sports is my life. Sport has really helped me to where I am, to raise me the way I am. I dream of playing on the national soccer team of Canada, going to the Gay Games, the World Games, meeting new gay people.

Uganda is a nice country, but gender? Uganda knows men and women only. Transgender is evil to them. They see you as Satan, as the devil. Lesbians can live because it’s hard for people to know, but in Uganda the transgender women and the transgender men are the face of the [LGBTQ] people. They are easily attacked. Anyone can easily beat you up. Recently, I lost my friend. He was burnt by the mobs. They stoned him to death because of his gender. They killed him. It’s not a good country for transgender people and gay people. They’re not safe. People live in the closet.

I came to Canada for the International Gay and Lesbian Aquatics Championships last summer, where I participated and won nine medals — eight golds and one silver. Before I came, I was arrested by the Ugandan police at the Mr. and Mrs. Pride event — I won Mr. Pride. I was beaten, undressed, checked if I was a man or a woman, forced into pictures. It was hard. When my family saw me on the news, they chased me away. They said, “You’re evil. If you come to our family, we’re going to kill you. We’ve opened a file with the police. We no longer need you.” Some things I can’t even say. It was hard. I couldn’t go back home after that. So I decided to stay in Canada. I miss my friends. I miss my mom.

There are a lot of good things going on in Uganda. There are activists; there are different organizations that are working tirelessly so that human rights are really for everyone. They are doing a great job. You know, the life I’m living right now in Canada, it’s like I’m living in the future. This is what I dreamed of. There are many people that are dreaming like this back home.

St. Paul’s United Church is a home for me. It has a good welcoming community. I was chased away from three churches back home because of my dress code, so I didn’t go to church for four months. I’m a man of God. I have to praise my God freely. So when I see St. Paul’s United Church — oh my God, it’s a welcoming place! It’s a nice place. It’s a home for the homeless, and it’s a free place where you can express yourself.

I believe God has played a big role in my life. I love Him so much. The relationship with me and God is so strong, and someone cannot just take it away from me. He has been my guide all the way.

I think it’s important for every queer person to have God in their life because He doesn’t discriminate. He doesn’t say, “People who put on skirts — don’t come here,” or, “People who put on trousers . . . ” He doesn’t discriminate. There is no gender in God’s presence, so everyone is the same.

Edmonton has good things — there are nice people. Also bad people. I’ve faced people who are bad, racist and transphobic. But that doesn’t threaten me because I’ve been through more than that. The queer community is so welcoming. Everyone wants to help. I’m thankful to them. Edmonton is a nice city. This is my home. I want to thank Canada for allowing me to be here, to be part of their country. I believe they won’t regret it.

The interviewer, Alison Brooks-Starks, is a writer in Edmonton.

‘When I first came, I said, ‘Oh my goodness, all these white people. Are they going to accept me?’ I’ve become their friend now. We are family.’

Afaf Abodigin

Age: 48

Country of origin: Sudan

Arrived in Canada: 1999

Attends: Knox United Church

Location: Winnipeg

I grew up in Omdurman, Sudan. My grandfather’s land is in the Nuba Mountains. We would go visit my grandparents in September when the corn was harvested. When I was 11 years old, my dad left to join the army in South Sudan. One day, my mom went to the Nuba Mountains with some of my siblings. While she was away, the government blocked the road and we were separated. The Sudanese Arabs wanted to get rid of us black people, to make Sudan officially an Arab country. They said that we were supporting South Sudan, and that’s why they closed the road. It was closed for nine years. I was with my two siblings in Omdurman. We thought that we had lost our parents, so we lived with my uncle; he was an alcoholic. At 11, I became like a mother to my two younger brothers. I dropped out of school and worked all kinds of jobs just to send them to school. Life was not easy.

At that time, I didn’t know anything about Christianity. My family was Muslim. There was an Anglican church close to our house. It had a women’s Bible study every Tuesday. One of the leaders was a relative, and I asked her a lot of questions. One day, I asked her, “Can you pray for us so that my mom can come back? My dad is far away — we don’t know where he is now. My brothers cry all the time because they miss my mom.” She taught me how to pray in Arabic, so then I started going to the church. I never missed a Sunday. Sometimes my uncle would say, “You’re not going to church!” I would just tell him my brothers and I were going to my friend’s house.

At the church, I met a woman named Gwen from England and her friend Ellen from Scotland. They invited us to their house in Omdurman and asked me if I wanted a job at the leprosy clinic. They said, “We need your help with the patients. You can clean the wounds if you can handle that.” I trained at the local hospital, and then I started working at the clinic.

My mom came back in 1994 and my dad in 1997. I don’t know how they made it. The army of Sudan was not killing people on the road anymore. Gradually, the road to the Nuba Mountains was opened again.

I met my husband through a friend. He has family in Omdurman, but he was living in Libya, working in a hotel kitchen. Because I worked at the clinic and was well known, they recommended me to him. He came to Omdurman [in the state of Khartoum] for a visit; we were married, and then he went back to Libya. He couldn’t go back to Khartoum because he was among the people who had supported the government of South Sudan. If he went back, he probably would have been killed. Instead, he sponsored me to come to Egypt. We stayed in Egypt for seven months, and then we came to Canada.

When we got to Winnipeg, there was snow. I was shocked. For three days, we didn’t go outside. I said to my husband, “This is real life? What am I doing here? I left my family, my sisters. I’ve never been away from my entire family. We’re going to live in the freezer like this?” I was sick for two weeks. But I’m still here. Now I have three boys. They are taller than me now, growing so fast. The oldest one is practising for his driver’s licence.

At first, we went to an Anglican church. Then, when my husband left me, I started coming to Knox United. When I first came, I said, “Oh my goodness, all these white people. What am I going to do? Are they going to accept me?” I’ve become their friend now. We are family.

I’ve been in Canada 18 years. I’m glad to have my children in a peaceful place. As a single mom, I don’t know how I would manage in Sudan. Sometimes if you’re in an abusive relationship, they force you to stay because of the children. I found my freedom here, freedom to say no if I don’t want something. Freedom to have a voice.

The interviewer, Josiah Neufeld, is a journalist in Winnipeg.

‘What amazes me is that when I look back, I see where God’s been, and I wasn’t aware of it.’

Corrine Danaher

Age: 71

Country of origin: England

Arrived in Canada: 2001

Attends: Noel United Church

Location: Noel, N.S.

My father grew up in East Noel, N.S.He was a Canadian soldier. My mother was a British war bride. They married in England, because of me, and he had to come back to Canada to be discharged after the war. It took several months for the paperwork for my mother to come through, so I was born in England but moved here in September 1946 when I was four months old. I don’t think the work was too brilliant in this area after the war, so within two years, we moved back to England.

David and I married in 1964. We have two children and three grandchildren.

In 2001, we stayed at a friend’s cottage on Lake Charlotte [east of Halifax], and it was so beautiful, so peaceful. We thought we would like to move here. The pace of life is so different, and we couldn’t afford to retire in England. It was just like coming home.

We went home and sold up and were back within four months. We came with 12 boxes and a keyboard. We stayed in Cole Harbour, N.S., with my cousin for the winter and moved to Upper Stewiacke, N.S., in May 2002. We bought a 36-acre farm.

We got a visit from Rev. Natalie Buchanan-Rutherford, and she invited us to church at Upper Stewiacke United. It very quickly became part of our lives. We rarely missed a service. Eventually, Natalie mentioned to David about going through the Christian Leadership Education (CLE) program. In conjunction with that, he did the Licensed Lay Worship Leader program.

I was with him all the way through, because I typed all his papers and went to his CLE meetings. I always went with David when he was leading a service. I was always telling him how he should do something, so one week I decided I’d do the service. When David was laid up for a year, I covered services all by myself. That really gave me the confidence to go anywhere we get called. I do this work, lay worship leadership, because I feel called to do it.

I begin each day with daily devotional reading. It usually takes me around an hour to read my devotions. I find if I’ve had a problem the previous day, I’ll find the answer in what I read. It’s never failed me, and it can be so definite. I’m not a journal person; it’s reading, and if I find something I like, I type it up and put it in a file.

We lived in Upper Stewiacke for 12 years, but we had to leave the farmhouse after David had two bad heart failures. For eight of those years, we lived in a mini-home. A friend who is a real estate agent asked us to come and look at a house, which was the Noel United Church manse. It had been empty for four years, but it just felt right to us.

The old school [in East Noel] is now a museum. I went in to have a look and opened up a newspaper. There was a photograph of my [paternal] grandmother and grandfather on their 50th wedding anniversary. People said I look like her, and when I looked at it — ah! — almost a double. One morning after I did the service in Upper Rawdon, this elderly lady came up to me and said, “Corrine, all the while you’re alive, your grandmother will never die.”

Back in 2001, when we said we wanted to move back to Canada, our children said, “Good on you.” My son [visited] when David had a heart failure in 2006. We haven’t been back home in 12 years. They do know if they wanted us for any reason, we would go in a heartbeat. I miss my children and grandchildren, but they have lives of their own, and we have such a full life here.

I am surprised how involved I am in the church. What amazes me is that when I look back, I see where God’s been, and I wasn’t aware of it. That fascinates me. For the last year in England, every time I walked past a particular church where we lived, I felt a pull to the church.

When we got involved in church here, I read a scripture that said, “When you serve me, you leave everything behind.” That’s exactly what we did.

The interviewer, Sara Jewell, is a journalist and author in Port Howe, N.S.

‘I fell in love with the country. I saw diversity I’d never seen.’

Rev. Ellie Hummel

Age: 51

Country of origin: The former West Germany

Arrived in Canada: 1984

Attends: Wesley United Church

Serves: Concordia University as a chaplain

Location: Montreal

I grew up in a town called Sindelfingen, which is just on the outskirts of Stuttgart in what was then West Germany. I grew up in a nice, liberal, white, Christian, middle-class environment. I was very involved in the Protestant church. I spent a lot of time volunteering. In 1981, I spent three months of Grade 11 in Toronto and went to a school downtown. That’s where I fell in love with the country. I saw diversity I’d never seen.

My friends tell me I was a real painwhen I came back, because all I talked about was Canada and how wonderful Canada was. I had big maps of Canada in my bedroom.

I was almost 19 when I came back in 1984 to work as a nanny, first near Kamloops, B.C., then in Victoria. I started looking for a church because church was really important to me. I ended up being a member at Victoria’s Oak Bay United. [The first time I went], visitors were welcomed and asked to identify themselves. I said, “I’m a nanny. I just moved here from Germany.” Everybody clapped. Everybody sort of flocked to me and said, “You gotta join our young adult group, you gotta do this.” I said, “Okay, I’m in!” Looking back, they were open to women in ministry; they seemed engaged in social justice.

I still love this openness. I love the wilderness. The big dream had always been to work in Canada for a year, cross the country, go home by boat somehow and live in Germany happily ever after. And I would have had a really good life. There was nothing wrong. I didn’t leave because of persecution. But there was something that kept me here, a sense of community. I really felt I belonged. I could almost reinvent myself. And again, that sense of diversity. People had possibilities.

In April 1987, I got my permanent residency and was a landed immigrant. I started at the University of Victoria that June. All my electives were Canadian stuff: Canadian history, Canadian politics, sociology. I just wanted to learn more. It was a bit of a stretch because I had never heard of any of this stuff: Champlain, who was he?

After that, I went to St. Andrew’s College in Saskatoon to become a minister. It was very progressive. I was by then in a relationship; I met my partner in 1994, the year I was ordained. She’s also a minister. I served in the ministry for five years in Saskatchewan. I love the Prairies for many reasons: the sky, the northern lights, the horizon. I still love Saskatchewan because it’s the cradle of universal health care and the co-op movement. Those are really my political convictions, too, and I think that as a country we have lost some of those values.

I’ll always be an immigrant. I’ll always be someone who moved here from another country and chose this country. I really feel I chose it, and I chose the United Church. In my current job [as the chaplain and co-ordinator of the Multi-Faith and Spirituality Centre at Concordia University in Montreal], I have the privilege of engaging with students in questions of faith, religion, values, spirituality and meaning. I see many students from around the world. I find them inspiring. They come here, and a year after they land, they do things like help refugees settle and find jobs, in ways I never did. I always get moved at those stories of immigration, when people find a home.

What I like about my current church, Wesley United, is that they are really inclusive. There’s diversity around ethnicity, around family configurations. They do a lot of work with kids.

I’m no longer German. When I became Canadian, I could not have dual citizenship from Germany, and I willingly gave it up. This is my sense of belonging. I’m very proud of it. I get leery about saying it’s the best country in the world. Because Germany said that in the 1930s and early ’40s, and it wasn’t a good thing. I still think there are other great countries, but I love Canada, and I usually say it’s the right country for me.

The interviewer, Bertrand Marotte, is a journalist and editor in Montreal.

This story first appeared in the July 2017 issue of The Observer with the title “From far and wide.”